MOBILITY | Desire Paths

Pedestrians should have the final say in the planning of foot traffic.

Written By Zoe Tishaev

“There is no logic that can be superimposed on the city; people make it, and it is to them … that we must fit our plans.” — Jane Jacobs

The merits of public input are a thorny subject in urbanist spaces, to say the least. But there are examples where public input is as valuable, and as sensible, as walkways. Often, colleges are regarded as ideal walkable bastions. They can only keep this reputation, however, if they build their campus to the needs of their students and retain these pedestrian-centric designs.

People are like water, moving along the paths of least resistance. Sometimes, that means taking the sidewalks—the paths drawn out by engineers and architects—but just as often, it doesn’t. When enough people deviate from the sidewalk to cut across a grassy knoll, to take a shortcut, or just to avoid a poorly placed lamppost, a desire path is formed. Desire paths (or lines) can be understood as “signs of a consensus [from users] that their way is worth walking; they are maintained only by the constant use of countless footsteps—without that, the lines fade and are forgotten.”

Desire paths are symptoms of bad engineering: The “intended” path of travel is not the one of most convenience for its users, so they make their own. Good engineering reflects the wills of the people, building sidewalks in accordance with natural patterns of drift. Nowhere is this dogma so clearly displayed than at some of the country’s biggest colleges.

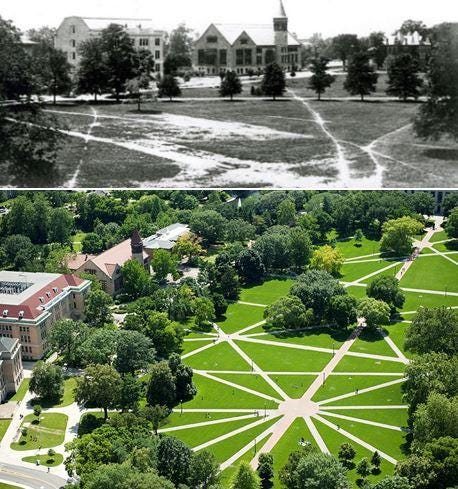

The Ohio State University may be one of the most famous examples, with the streamers of concrete around the Oval of campus being a direct result of paving over the frequent footwork of students in the 1920s.

More recent examples include the construction of the McCormick Tribune Campus Center at the Illinois Institute of Technology around areas that were studied to have desire lines in 2003, the formalizing of Michigan State University’s paths in 2011, and the decision by Virginia Tech to pave over three desire paths on its Drillfield in 2014.

Not all colleges are on board. Recently, Duke University made the decision to rip out several well-trodden brick pathways (that themselves were once desire paths) and replace them with bushes. This move speaks to a broader tension in the design of universities, not to mention greater cities: When can the modern supplant the historic? How much leeway should a designer today have over the future and past patterns of mobility?

The answer should lie with the users. People vote with their feet. If we design urban environments for the benefit of the people who use them, then only they can decide whether a pathway is worth keeping. Used pathways should be paved and maintained, while those that fall into disuse can be repurposed with greenery and other forms of life.

Zoe Tishaev is the Spring 2023 Duke Initiative for Urban Studies Fellow on Transportation Alternatives and University Development.

Very nice examples. I also wrote about the desire lines I see on Erwin rd. https://sites.duke.edu/davidbradway/erwin-road-is-a-heavily-used-bicycle-and-pedestrian-corridor/