ZONING | The Need to Rewrite Codes

Bloated modern ordinances prevent citizens from being citybuilders.

Written By Zoe Tishaev

In the not-too-distant past, at the advent of suburbanization in the early twentieth century, it was quite common to purchase a prefabricated house. Sears was famous for their catalog homes, which came in 447 different designs and were sold to customers ready and eager to build their dream home. Today, development is a more arduous task. With myriad codes, authorities, regulations, and restrictions to leap and bound across, development has become a massive industry, replete with the accompanying inspectors, bureaucrats, lawyers, and developers to make it all work. The level of detail in today’s codes can be staggering, shutting out the average person trying to take part in building their city. To see just how convoluted these modern codes are, I read the Durham, North Carolina, zoning codes from 2022 and 1926. Here’s how they compare.

The Durham Unified Development Ordinance (UDO) in its current form was enacted in 2006. The UDO “designates zoning of properties in Durham, and is crafted to result in a built environment that meets the goals of the Comprehensive Plan,” according to the City’s website. In full length, it is 747 pages—complete with indices and various tables, charts, and definitions.

The UDO is a behemoth. It’s clearly not meant to be read in one sitting, as Durham specifically provides a searchable digital version, broken down into 17 articles, each with around eight sections. The UDO details the specifics of everything, from the various zoning codes to the types of signs that are not allowed (including permits to limit “excessive animated signage” in an area).

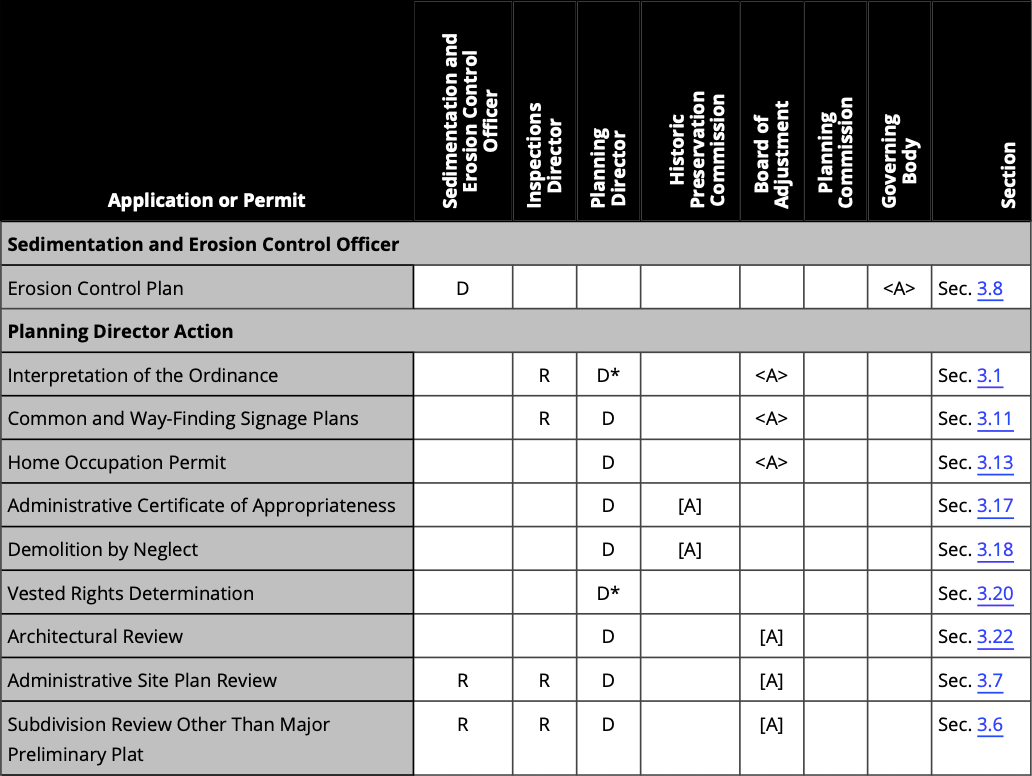

The first task of the UDO is to attempt to untangle the bureaucracy around zoning—a task much easier said than done. The UDO dedicates 15 pages to describing the “who’s who” of Durham Zoning, including the Joint City-County Planning Committee, the Planning Commission, the Board of Adjustment, the Historical Preservation Committee, the Inspections Director, the Planning Director, and a whole host of other actors. Want to know what each of them does? Simply consult the helpful two-page table that describes which authority needs which permissions for each type of permit. I’ve included an abbreviated visual here.

Finding the right authority for your questions, however, does not mean you are ready to build. More often than not, many permits and construction projects require a public hearing. In fact, the phrase “public hearing” is mentioned 159 times in the UDO. There are regulations not just for when to have a public meeting, though, but also for how to advertise one. Notices for all public hearings must be published “not less than ten days nor more than 25 days before the date fixed for the public hearing.” Sometimes notices must be mailed, and if they are, they must be sent at least 14 but not more than 25 days prior to the date of the public hearing (3.2.5.B). And so on.

It would be impossible to tackle the entire UDO in a brief piece like this. So let’s look to the twentieth century for a comparison.

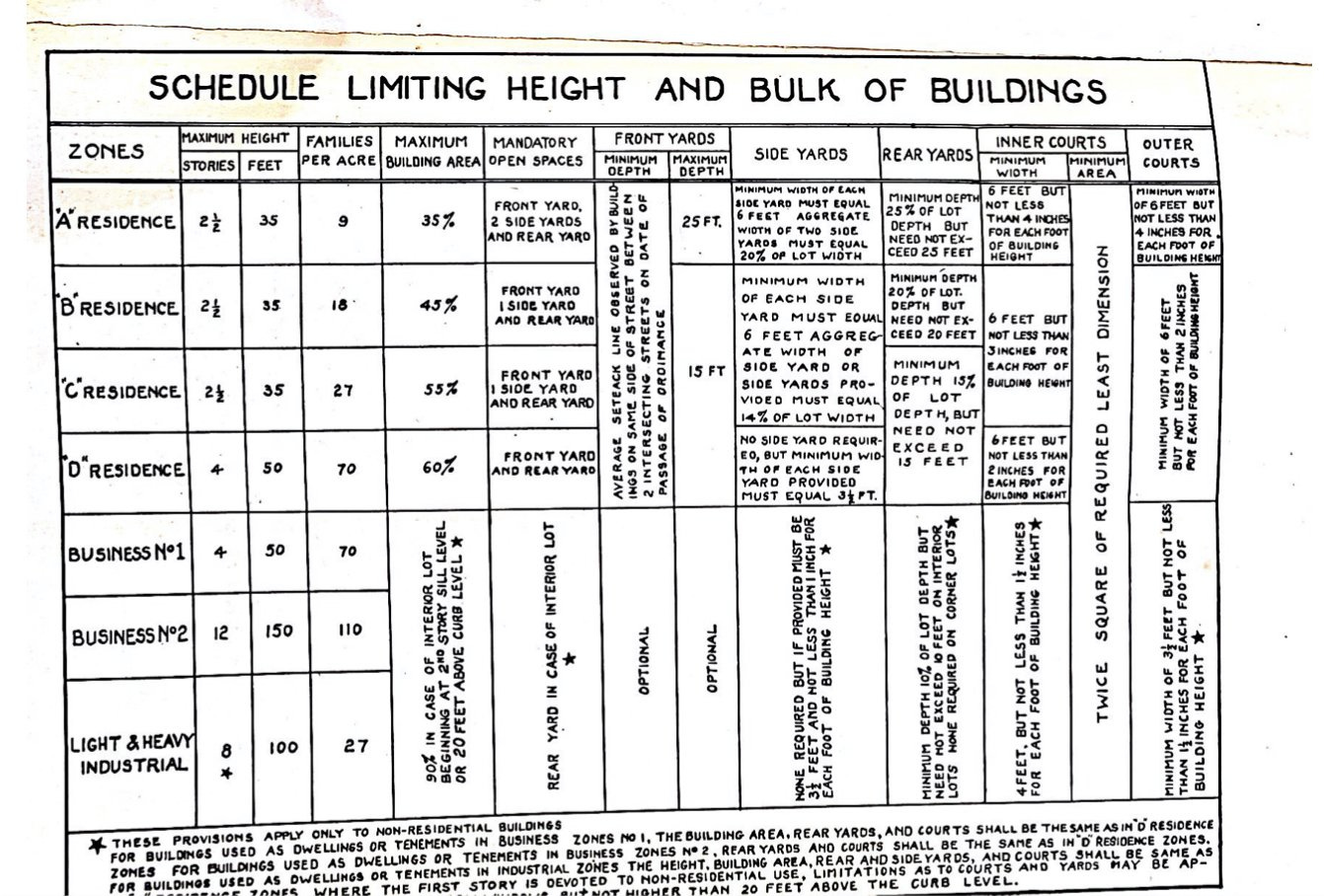

The first thing you notice when opening the 1926 zoning code is its brevity. Clocking in at 16 pages, the 1926 ordinance is a quick read you can pore over at the breakfast table. The second most striking part of the older code is that the language used is restrictive rather than prescriptive—the code only designates things that you cannot do, rather than explaining the process on what you can do. There are four basic zones: residential, business, light industrial, and heavy industrial. Each zone has a section that outlines 10-40 bullet points on what cannot be built in each zone. Outside of what is explicitly prohibited, property owners have free rein.

There is only one table in the 16-page zoning code—a clear chart that describes the basic guidelines for yard and spacing requirements.

You can read the old Durham zoning code for yourself here and admire its simplicity. But the fact is: As laws and standards have gained complexity over time, so has our fundamental zoning code—to the point where a member of the general public could not reasonably be expected to fully understand it. The most essential blueprint for building our cities has escaped the comprehension of any one person, and with it has disappeared his or her ability to build and shape the built environment. The bureaucracy around this entanglement is self-sustaining: We need inspectors to enforce the codes, and the codes must reflect our standards.

Most of the cities we treasure today were built in a time when the zoning code was straightforward and easy to digest. This was an era when cities were the product of efforts by its citizens, before the massive industry of development, inspections, and zoning consultants. It’s true that cities in the last hundred years have come a long way in safety and environmental legislation, but they should be careful not to encroach on the ability of residents to play an active role in developing their city.

Jane Jacobs wrote in her book The Death and Life of Great American Cities that “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” But cities cannot be created by their citizens if the citizens cannot understand the city’s blueprint. 747-page zoning codes, heavy with jargon and incomprehensible tables, make building inaccessible to average people who don’t have a staff to help them decipher it. Cities need to radically simplify or even rewrite their zoning codes, disempower bureaucrats and code inspectors, and place the reins of citybuilding back in the hands of the people.

Zoe Tishaev is the Spring 2023 Duke Initiative for Urban Studies Fellow on Transportation Alternatives and University Development.