I’ve spent most of my formative years in two small towns—one in the South, one in New England. It pains me to say it, but New England has the edge. Almost every small town in the region is incredibly walkable, with a cute central “green” surrounded by civic buildings and local businesses. One of those civic buildings is almost always a church.

The white Congregationalist steeples are a hallmark of the region, appearing in tourism ads and postcards. A quick Google search for “Vermont” reveals that every other image has a church. The same is not true for Southern states. Evidently, these churches have successfully associated themselves with the expectation of a quaint small town. Yet the formula to their success is simple: they are located in welcoming, walkable areas.

By embracing density and maximizing their small footprints, New England churches have become iconic symbols of their communities.

In contrast, houses of worship in the rest of the country (especially in the South) are too often disconnected from their communities by large parking lots or unused land. Faith-based housing presents an opportunity for these religious institutions to reimagine their relationship to their surroundings, becoming as renowned as New England churches by surrounding themselves with beautiful, lovable places.

Let’s compare a New England town with a Southern one to see how their houses of worship use land differently.

Example: Woodstock, Vermont

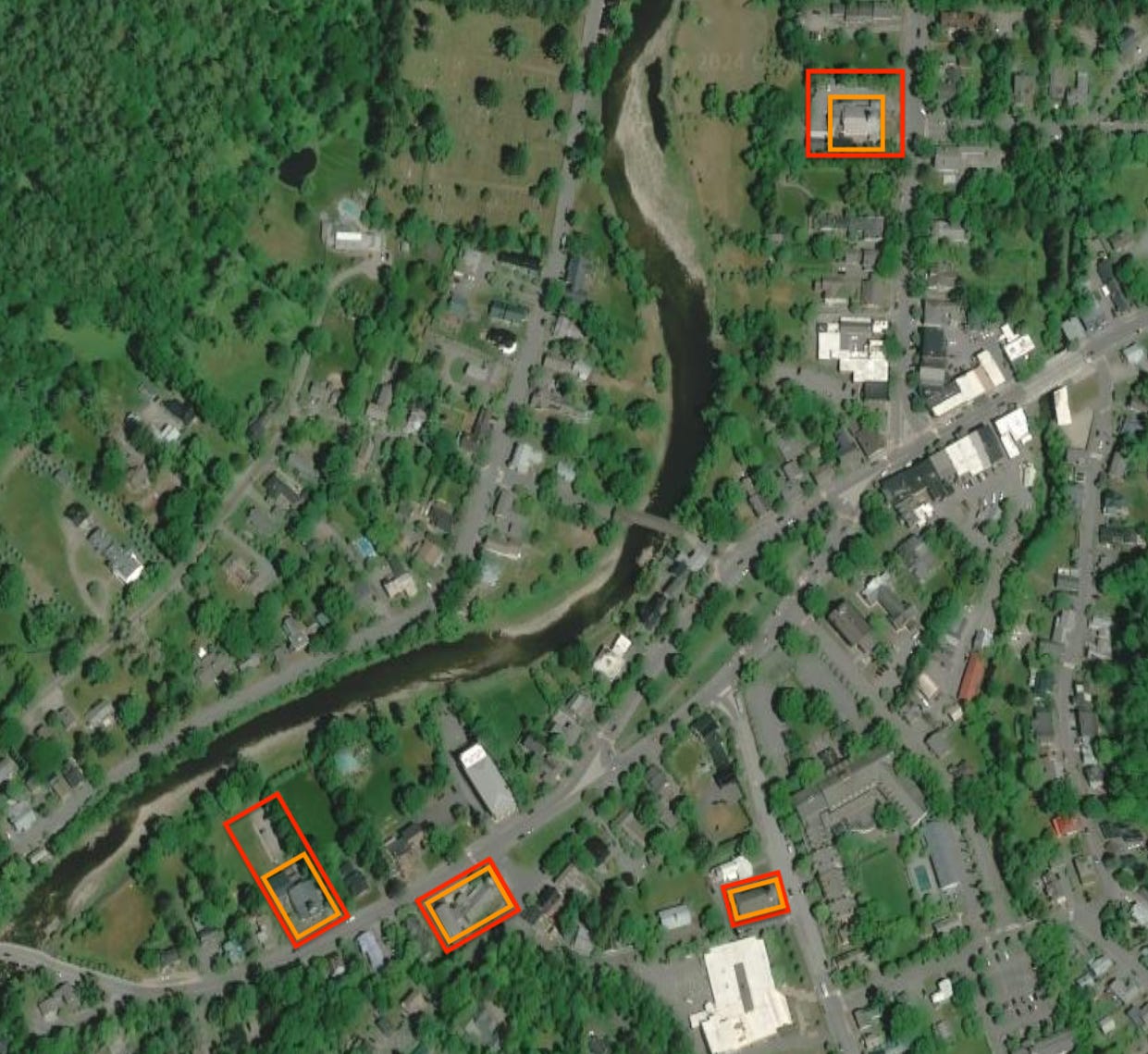

Woodstock is regularly listed as one of New England’s best small towns. It’s got everything you could ever want from a Vermont town: historic buildings, a nice town green, even covered bridges that are in town. It’s also home to a number of beautiful churches whose steeples regularly make it onto postcards. Let’s take a look at the four churches in Woodstock’s downtown.

The church properties here are boxed in red, with the actual physical churches being boxed in orange. As you might notice, two of the churches occupy the entire plot of land that they sit on. They do not have any dedicated parking (though they are both quite close to a larger lot), nor do they have large unused tracts of land. The two that do have parking have it tucked either behind or beside the main building.

Example: Asheboro, North Carolina

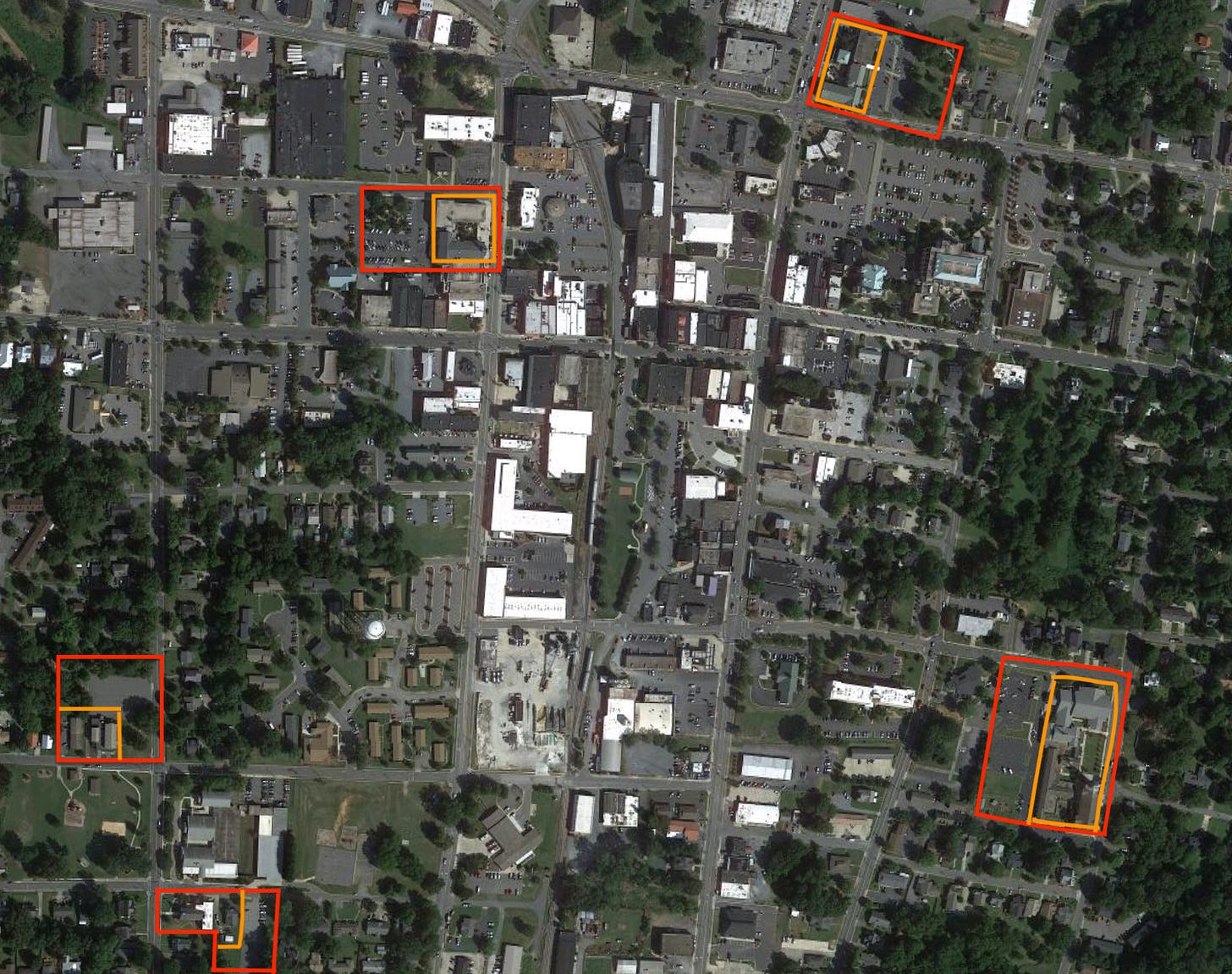

Now let’s compare to my mother’s hometown of Asheboro, North Carolina. Asheboro is a town whose historic center was hollowed out by deindustrialization, then by the expansion of a large stroad on the edge of town. Though it has been revitalizing in recent years, the downtown is still characterized by empty lots and excess parking.

Another thing that Asheboro has? Churches.

Most of these sites are over half parking. Similar to Woodstock, though, the parking lots are tucked behind or beside the main buildings. However, they are often so large that they take up the entire side of the block. These are large lots that sit empty most of the week, providing little more than convenience on Sunday morning.

These aren’t churches on the periphery- they’re all within walking distance of restaurants, shops, and parks. Faith-based housing projects on these lots would add walkable density, making the town and its churches more welcoming to pedestrians. In a city that has incredible historic buildings begging to be restored and a downtown that is trending toward a comeback, these churches are perfectly positioned to show the rest of the city what Asheboro could be.

It should also be mentioned that Lydia’s Place is a great example of a church converted into housing in North Asheboro, just up the street from these sites. The potential for expanding this model into downtown is tremendous, and the success of Lydia’s Place should serve as encouragement for future faith-based housing projects in the area.

Of course, there are many more boxes that would have to be checked for any of these Asheboro churches to build. For starters, Asheboro’s stringent parking minimums would be tough to get around, and that’s without even getting into financing. But the example still holds: American churches, particularly in the South, have long placed a large concrete barrier between themselves and their communities.

New England churches haven’t, and its allowed them to stay more connected with their surroundings. Despite being the least religious states, New England steeples remain a calling card for their small town way of life, inseparably serving as unifying institutions. Their buildings regularly serve as multi-use gathering spaces for town meetings, cultural events, and some of the best concerts I’ve been to.

Yet Southern churches also have an advantage—they have an empty canvas to create a better version of their town. Faith-based housing allows houses of worship to rethink their physical presence, surrounding themselves with more than just a sea of parking. In a small town, transforming just one block transforms the entire town.

If institutions of faith are willing to engage in that kind of transformation, they may find that they become just as iconic as their New England counterparts.

Eli Smith is a senior at Dartmouth College studying Religion and Public Policy. He is the Faith-Based Housing Initiative’s Research Fellow.

I live in Utah, and aside from some of the historic Latter-day Saint temples in Salt Lake City, Logan, and Manti, the average LDS church is just so... uninspiring. They face the double whammy of bland, functional architecture, and oversized parking lots. The giant parking lots seem especially egregious in an area where the density of Latter-day Saints is so high that you practically can't find somewhere to live that isn't within a 5-minute walk of a chapel, do we really need that much parking? It seems like a perfect example of plentiful free parking inducing car trips that could otherwise be made by foot. These churches are the heart of public life for many of these suburban neighborhoods but still never manage to be iconic in the same way that churches in the much more secular New England region are.