The Importance of Magical Places

How do we move beyond the utilitarian in our cities & towns, and into the sublime?

Southern Urbanism has partnered with Building Optimism and Building Culture to bring you the best stories from the people who build our cities. In his most recent essay, Coby Lefkowitz explains what we must do to bring back inspiring development.

Much of our contemporary built environment suffers from being overly utilitarian. For a select few places, there’s an embarrassment of cultural riches, amenities, and exciting things to see and do. But this isn’t the case in most of our cities and towns.

In most communities, we have a box that we sleep in, a box we drive to the office or school in, and then, once we’re there, a box to work or study in. At lunch, we often go to a generic box that can be found in one of several dozen cities, and repeat the same thing every day. Occasionally, but less and less frequently, there may be some other box that we go to the movies in, see a show in, or go out to eat in. These places are often devoid of any ornamentation, idiosyncratic details, or contextual elements that would ground them in a specific community. They’re hastily thrown up structures made of cheap materials, with sometimes cheap detailing, that allow for the bare minimum exterior experience, concentrating efforts on insular spaces (if they even do that). These places do not elevate our collective experience, and threaten our psychological well-being.

This doesn't mean that the homes, offices, restaurants, or third spaces (to the extent that they even exist) in our cities and towns aren’t nice, but just that most places in America neglect a communal and street level experience altogether. Our private spaces are valued much more highly than our public ones, and it shows. As most communities have been redesigned, or designed from the ground up to be driven through at fast speeds on cars, there isn’t much detail considered to what the structures look like. A plain box with faux architectural design elements looks the same as an intricately designed structure of the same shape when driving by at 60 miles an hour. Of course, when one is moving by at walking or biking speed, the details of a structure are more apparent.

Instead of reinvesting into the quality and character of our communities, we’ve value engineered them down to the lowest possible viable design, thinking that design itself is superfluous. “Who cares about higher quality materials, considered massing, good urban fabric, or ornamentation?” the average participant in the built environment might ask, continuing, “Life seems to be working perfectly fine now without all of that. We don’t do that here, and based on my subjective quality of life, we get it right.” We travel around the world to experience these exact places, but for some reason sneer at the possibility of creating them in our own backyard. Those places we seek out have spirit, personality, grandeur, and excitement sufficiently high enough for us to spend thousands of dollars just to get a few scarce days in their presence. Surely this is a more outrageous proposition than making the building that is already going to be constructed next door a little bit better.

There was a level of craftsmanship that transcended mere ornament. Buildings were adorned with art of the highest quality, including statuary, frizes, mosaics, paintings (The Sistene Chapel in the Vatican, famously), for few reasons other than the pride of the benefactors and artisans who worked on them. While there were certainly other motivations beyond pride, like advertising one’s wealth, power, or piety, the public—and posterity—have been able to enjoy these treasures. While garish by today’s standards, regular places have effectively become museums in situ for many to enjoy that have compounded advantage over much time (centuries, not mere seconds or hours in our culture of incessant instant gratification), as opposed to 0s and 1s in trust accounts managed in Switzerland, New York, or online.

While highly ambitious buildings and environs may cost more money than the utilitarian alternative (though not always, especially when the infrastructural and taxation consequences of a sprawling car dependent society are factored in), they play a critical role in communities. Our buildings and places symbolize what we value. They tell the story of who we are. A city of richly adorned churches or mosques may be pious, where funds are constantly reinvested into those structures to create ever more aspirational halls of worship. A city home to many theaters and galleries is one that welcomes the arts with open arms. And somewhere that pushes the bar on design can be seen as valuing innovation, dynamism, and embracing a more optimistic future.

What story do our prevailing development patterns of homogenous strip malls with the same chain stores, mega highways, and acres of tract homes say about us? That we worship cars? That our communities could easily be replicated with identical structures that are equally as placeless? That we’re cheap? That we hate the environment? That we value corporations over the idiosyncrasies of local businesses within a unique neighborhood fabric? Few people would say these things about their rich networks of social relationships and intimate connections in their community. But that’s precisely the story their built environment is telling. We no longer translate our intangible ambitions, successes, and stories into the broader built environment. It’s as though we’ve severed the very soul of our communities.

It’s true that we don’t need anything more substantial than a simple box to live in. Everything that doesn’t directly contribute to survival is, strictly speaking, superfluous. But what kind of life is one that accepts the bare minimum? Certainly not one that has any relation to the long march of prosperity humanity has made over millennia. With this march, we’ve mobilized out of bare subsistence, and demanded more of our world. Even the most ascetic worship at the feet of grand monuments. Since the Great Pyramids of Giza, to the Ziggurats of Ur, and through skyscraping medieval churches, we’ve always sought to reach higher, express ourselves more completely, and give to posterity that which may be limited in our own day. These buildings and places come to define us for generations, and represent a power greater than us as singular individuals.

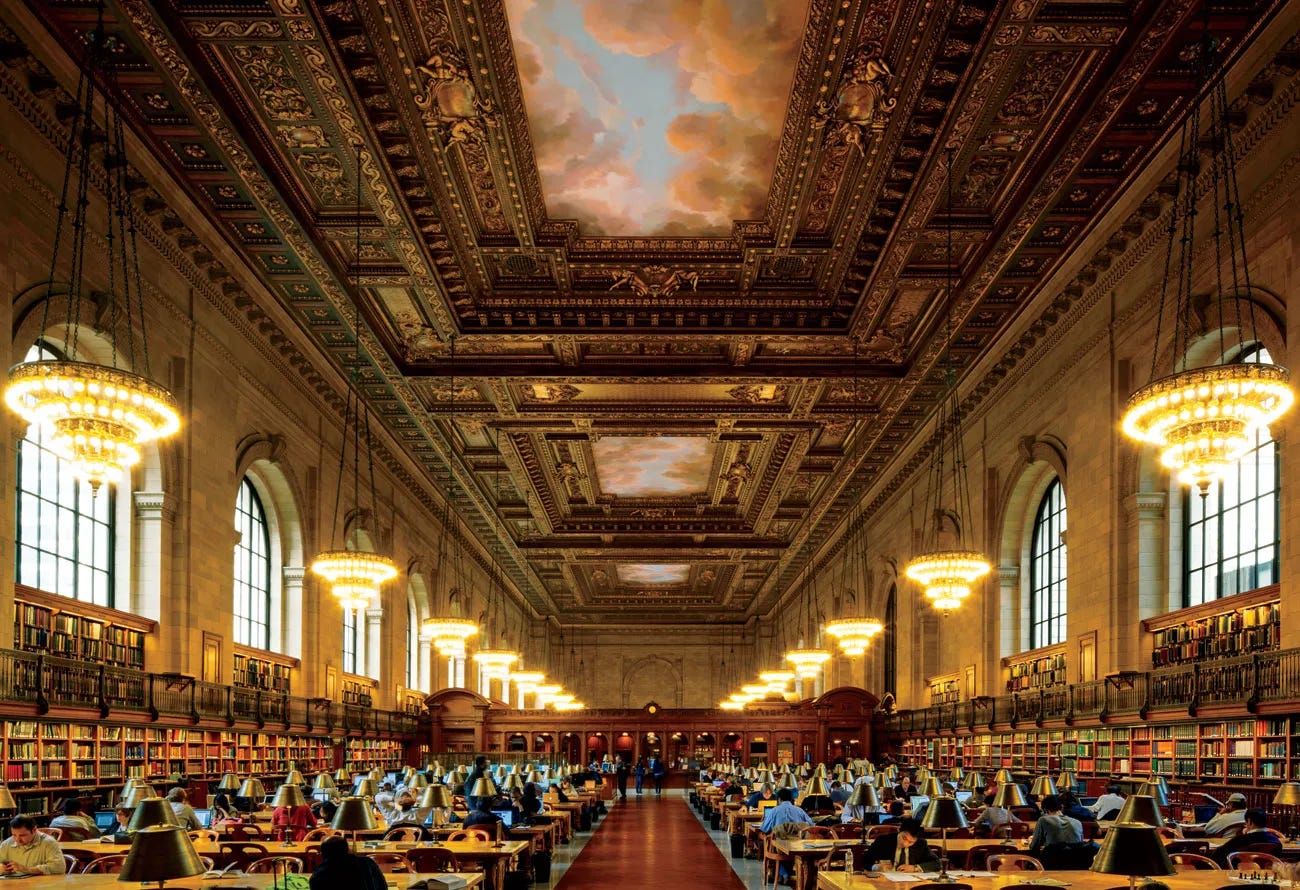

We might call these magical, or fantastical structures. They push so far beyond the quotidian norm, and have the capacity to inspire us so deeply, that they feel in some way separate realms from our own. When defining the word fantastical (strange and wonderful, like something out of a story), The Cambridge Dictionary adds an example for further context; “Fantastical Buddhist temples and medieval castles cling to Bhutan's misty valleys.”

You can feel yourself in this setting, and understand the narrative of the place.

Would our lives not be improved if we had more of this sort of enchantment? Is life not more fun when what’s around the next corner is not only unexpected, but full of wonder? Whether a fleeting moment that gives us a temporary reprieve from our day, or an immersive experience that transforms our perception, our built environment has a unique ability to influence how we interact with the world.

While changing this isn’t an overnight process, it’s something we can kick start today, even at the smallest scales. It doesn’t take much. Indeed, this is how many of our most magical places evolved. They weren’t built to a finished state on day one, but evolved over time—and were sometimes rebuilt completely—to include more details, better materials, and art, where the patina of age has worked its way to confer a romantic charm only earned through an arduous journey of countless histories imbued into a structure, that only then reveals its beauty. But any small step along that path can be wonderful—whether it’s a few string lights, a mosaic, or some small facade pattern that bucks the status quo. We revere the stories that are carried in the bricks and glass of these places. We strive to learn their mysteries, inevitably failing, but still compelled to push forward. There’s a thread that ties us to this past, and continues onto the future. A linkage of humanity that’s forged in a common bond, where we may be able to add some small piece to this great tapestry. To turn a fantasy ever closer to a reality. A power to a small wooden hut being turned into a grand monument to progress, faith, or pride over much time. And, for those transactionally minded, pay a significant premium to live in or near them. This can’t be said of the mundane.

There are many places that have been created in the past that inspire this type of magic–winding medieval streets with imperfect but enchanting background buildings come to mind. One of the greatest magicians of the built environment was Antoni Gaudi, Barcelona’s master designer.

Gaudi’s buildings are Sui generis, in a class of their own artistic quality that goes well beyond normal convention. Through mosaics, local materials, and motifs, his projects are steeped in Catalan context. But they extend so much further from this foundation. Places like La Sagrada Familia, Park Guell, Casa Batlló and Casa Milà–among many others–demand attention when one walks by. Through their amorphous shapes, vivid shocks of color, whimsical reimagination of traditional architectural elements like balconies and columns, and high degrees of ornamentation, they defy all normal convention. And yet, they’re among the world’s greatest structures, perhaps because of their defiance. While none of these buildings needed to be anything more than a box for living, worship, or work, they elevate the everyday experience to something that’s difficult to put into words. These buildings are simply magical.

Contemporary architects have relearned these old lessons in recent years, and have begun imbuing more magic in their work. Though some critics may initially wave them off as vanity projects, they tend to be massively popular among the general public, and work their way into the hearts of even the most cynical nonbeliever over time. This has manifested in a few different ways. From starchitects carrying out fantasies dreamed up by the super rich, super powerful, or both, to historically marginalized communities embodying remarkable stories from their community in more modest, but no less enchanting, ways.

Let a few pictures below expand your capacity to dream for a better world and inspire you, as they’ve been built once before, and can be built again, in new and exciting ways. Some may be familiar. Some may not. But all condemn the quotidian, the mundane, the utilitarian. They don’t need to be as spectacular, or whimsical, or quirky as they are. And yet they are! This is their simple, yet remarkable power. They could as simple as a box. And yet they’re not! There’s some great excitement to this, and something deeply moving. While a high quality urban fabric is essential towards the creation of better communities, it’s the extraordinary, and sometimes nonsensical, buildings that lend identity and imbue character to a place. They punctuate the skyline, penetrate our hearts, and occupy outsize space in our minds. They are the fantastical, but they are not fantasy.

And millions more magical moments!

Coby Lefkowitz is a real estate developer, writer, and thought leader in the world of urban planning and development. He recently published the book Building Optimism, explaining why our world looks the way it does, and how to make it better. Purchase your copy, via the link.