Small Homes and Small Lots

Durham, North Carolina's reforms chart a new path to lowered housing costs.

In 2019, the City of Durham, North Carolina, passed a set of reforms known as Expanding Housing Choices (or, colloquially, EHC). The reforms were created by planning staff at the directive of Durham’s City Council and were anchored by:

The end of single-family zoning

The creation of a transformative Small Lot Code

The introduction of Reduced-Pole Flag Lots

While relatively limited in scope, these three features were almost immediately incorporated into urban development plans, creating small micro-communities, more viable opportunities for citizen-built housing, and, remarkably, the reconstruction of a starter-home market that had effectively collapsed.

Each of the three features outlined below contains elements that other cities should emulate.

l. The end of single-family zoning

Single-family zoning has an ugly history in the United States, clearly rooted in racial motivation. The first such code started in Berkeley, California, in 1916 as a means of limiting access for the less wealthy who, at an acute moment of racial strife, happened to be black. After the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, politics drove planners to radically expand single-family zoning, with many cities implementing it only then for the first time. It is no coincidence that Durham’s first instance of single-family zoning code was passed in 1969.

When discrimination based on race became illegal, exclusion became a game of Whack-A-Mole through increasingly technocratic proxies, none more effective than single-family zoning. There were others, too, all related to single-family considerations, such as mandating large lots with large setbacks, large parking requirements, and large lot widths.

All of these rules added costs to housing, intentionally discouraging those with less wealth.

Durham’s code even created a racial distinction between the most dominant urban zoning districts, RU-5 and RU-5(2), by permitting duplexes in black neighborhoods while disallowing them in white ones. All of that came to an end with the passage of EHC, when Durham’s City Council repealed single-family zoning exactly 50 years after it was passed.¹

Practically, what does getting rid of single-family zoning mean?

In Durham, a few things changed:

Builders and homeowners could now build duplexes, by right, and “attached homes” (which are effectively just duplexes with fee-simple lot lines).

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) became allowed on duplexes as well, potentially yielding a total of three homes on most lots.

Duplexes could be detached, triggering a wave of opportunities for what incremental developer R. John Anderson calls “stealth pocket neighborhoods” (the form that looks like Ross Chapin’s book), a housing type that does not depend on being specifically allowed by the code. In Durham, urban designers can use the existing code that allows three homes on a lot and arrange those homes in a way that enhances community space to the benefit of all.

New construction rental projects that were not financially viable before suddenly became so by spreading expensive land costs across multiple houses. This helped restart a mostly dormant neighborhood-scale rental housing market. This market includes homeowners who, when building their own house, can now build two additional homes, which can pay for some (sometimes all) of their mortgage. A select few homeowners have acknowledged the truth of this seemingly unbelievable math: The best way to create affordable housing for yourself is to simultaneously provide some for others. And just like that, citizens are getting back into the game of homebuilding.

ll. The Small Lot Code

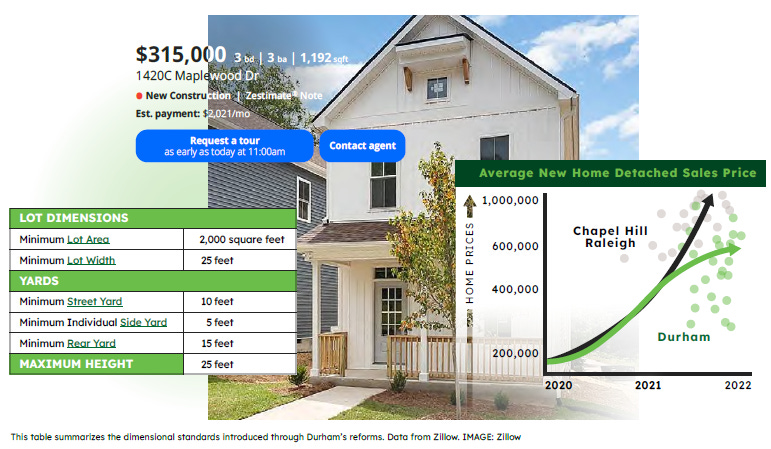

The most unprecedented and transformative reform in EHC is the introduction of the Small Lot Code. This allows for new homebuilding on lots up to 2,000 square feet, contingent on the home being a maximum of 1,200 square feet heated, 25 feet tall (measured to the midpoint of the roof in 2019, but reformed to 32’ ridge in 2023), and 800 square feet in terms of footprint. It also allows for smaller corner setbacks, which are necessary in a city with largely anti-urban front yards.

The Small Lot homes may also be duplexes (dividing the 1,200 square feet between the units) and have detached ADUs that allow for an additional 1,200 square feet.

The Small Lot provisions have been adopted faster than expected, with more than 50 units already built and more than 100 in the pipeline (2022 data). Astonishingly, it appears that the majority of new detached homes being built in the urban tier of Durham are ones with Small Lot permits.²

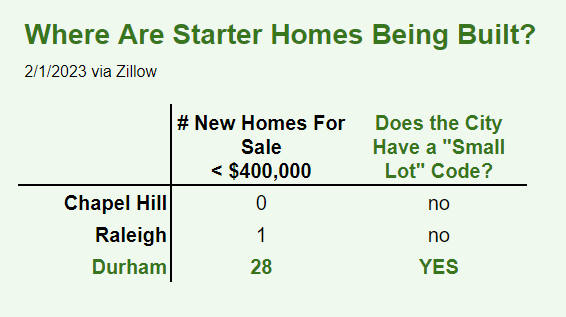

The effects of this code can be seen in the area’s average home prices. Durham has generally been the tightest, most highly sought-after market within the Triangle region. But the provisions of the Small Lot Code appear to have already “bent the price curve,” reintroducing starter homes into a city of over 250,000 that has recently announced major Google and Apple campuses and has speculators rushing into town to buy homes sight unseen. Since 2020, Durham has had 50 new detached homes sell for less than $500,000, while Chapel Hill and Raleigh have had zero.³ That’s the Small Lot Code at work.

Another consequence has been the cottage industry of designers that quickly formed to service this market. For example, Bill Allison is a veteran architect with Allison Ramsey Architects armed with a catalog of 3,500 stock plans—all Southern traditional. He created a set of plans that conformed specifically to Durham’s code.

In addition to the dozens of plans done pro bono for affordable housing in Durham, he’s had multiple local builders purchase Small Lot plans, too. As Allison put it, offerings like his make it easier for people to go down this path: “Small homes are great, but they require a lot of design nuance. Once you understand the constraints, you can create efficient spaces, and you can arrange multiple small homes to create a uniquely Southern urban experience. Tall windows, deep porches, eave details, and so on.”⁴

lll. Reduced-Pole Flag Lots

Durham also implemented a unique Reduced-Pole Flag Lot (RPFL) option based on community feedback that the previously required pole width of 20 feet was effectively unusable almost everywhere. Reducing the required pole width to 12 feet while restricting homes on these lots to the same dimensional standards as above created a wealth of opportunities for small rear-located housing that could never have been built before. The RPFL option has become a critical tool for exploring the potential of micro-community developments. Such possibilities now seem endless, and entrepreneurs are drawing up new business plans that provide more housing—and better housing—in community-enhancing formats than have ever been seen in Durham before.

National Implications

To all but the most ardent “Not in My Backyard” (NIMBY) voices, EHC has been a success. President Biden even borrowed the program’s language for his Housing Supply Action Plan (Fannie Mae did similar, as did San Francisco).

It’s been strange to see Durham not get more press for the reforms. Perhaps this is a function of the city's lack of self-promotion or of its relatively small size. But the EHC provisions are clearly valuable, and cities across the region should examine them and their results.

If we are to keep the South accessible and affordable while also urbanizing it and making it walkable and beautiful, there are no pain-free approaches. Such work is overwhelmingly incremental and requires densifications at the margins. The West Coast shows the clear costs of only permitting homes for the rich. Over time, it’s disastrous—for everybody. Small, incremental homes on small lots—that’s the way forward.

Durham has taken that step better than anyone. Now, others should follow. SUQ

Aaron Lubeck, Jacobs Columnist, is a new urban builder and land planner in Durham, North Carolina. He is the author of Green Restorations: Sustainable Building in Historic Homes, and a children’s book on Accessory Dwellings entitled Heather Has Two Dwellings, and host of the National Townbuilder Association’s “Townbuilder’s Podcast”. @aaron_lubeck

NOTES

Although Durham paid city planners from Minneapolis to come down and explain how they repealed single-family zoning, Minneapolis had only stated an intent to do so and had not actually repealed anything at the time. In the end, Durham actually repealed single-family zoning before Minneapolis did— even though Minneapolis has received substantial press for the move and Durham virtually none.

For more information, see the City of Durham’s handout “Small House/Small Lot”: https://www.durhamnc.gov/DocumentCenter/View/24691/Small-House-Small-Lot-PDF.

Source: Zillow data.

The author does minor work with this firm.

@aaronlubeck "In Durham, urban designers can use the existing code that allows three homes on a lot and arrange those homes in a way that enhances community space to the benefit of all."

I looked up Ross Chapin. Would love to see some local examples of these pocket neighborhoods. Can you point me in the right direction?