Progressive Cities Aren't Living Up To Their Values

How ideology is getting in the way of good city building

Southern Urbanism has partnered with Building Optimism and Building Culture to bring you the best stories from the people who build our cities. In his most recent essay, Coby Lefkowitz explains how progressivism sometimes gets in the way of progress.

Progressive cities have been telling themselves a myth for (at least) the last 20 years. Conjuring an identity based on virtue, and strengthened by a sort of moral superiority that looks down its nose at every other part of the country, large, prosperous, and blue cities have come to believe that they’re the champions of the marginalized, working and middle classes, carrying the torch on policies that everywhere else should seek to emulate in the pursuit of more equitable communities. Places like New York, San Francisco, Boston, Seattle, DC, and LA (among others), have held their heads high, perhaps too high, incredulous that anywhere else could be as successful, desirable, or noble as them. As the bastions of the intelligentsia with the best schools and culture, most amenities and enlightened values, who else could compete?

Maybe that was true one day in the past, but not today. This belief has largely not been met in reality. These cities have rested on laurels earned from the hard work of prior generations. The truth is, prosperous progressive cities have largely failed in the progress that should be at core of their mission. It’s right there in the name! People can argue online about how they feel a city is doing, and that’s all well and good, but the data doesn’t lie. We, and I use “we” to include myself as a progressive who has lived in several of these cities, have not lived up to the values we claim to embody.

I’ve used the word progressive a few times so far, so, before going further, I’d like to define what exactly I mean by it. I’m not using it as a stand in for “left” or “Democrat” in the context of our modern political system of conservatives v. progressives. Rather, I’m using the word to explain the intention behind progressivism. Tim Urban uses a definition in his book What’s Our Problem that I think works well:

Concerned with helping society make forward progress through positive changes to the status quo. That progress can come from identifying a flaw in the nation’s systems or its culture and working to root it out, or by trying to make the nation’s strong points even stronger. If the country is a car, progressives are in charge of the gas pedal.

Through this lens, we can analyze whether progressive cities are moving forward with positive changes to the status quo—the only true barometer of progressivism. We know the status quo is riddled with serious challenges, so, how are they doing in response to them? Not great.

Rents are at historic highs. Of the 10 most expensive cities by rent in the US as of February 2023, 9 of them were solidly progressive cities. The 10th, Miami, has a purple streak, but is moderately progressive compared to the rest of the country. It’s important to note that these are city-wide medians. High quality apartments that are closer to jobs, amenities and public transportation are considerably further along the rent curve. Los Angeles is a very large city, so while the median rent may only take the 7th place on this list, living near the beach in Venice would be costly enough to earn the 2nd place on the list. When you take the average, and not the median, the most expensive apartments drive up the rent for everyone else. In Manhattan, the average one-bedroom is $4,200. Apartments in buildings with doormen will run you more than $5,100.

These places aren’t just expensive, though. They’re economically eviscerating the people who live in them. This disproportionately harms the marginalized and working classes progressive claim to be looking out for. HUD classifies affordability as “housing on which the occupant is paying no more than 30 percent of gross income for housing costs, including utilities.” In New York, nearly 70% of renters are rent burdened, spending more than 30% of their gross income (before taxes!) on housing costs. This is only the tip of the spear in a country where half of all renters, amounting to 20 million households, are burdened by housing costs. 10 million renters are severely burdened, spending more than half of their gross income on housing.

When you spend more than half of your gross income on housing, you’re faced with decisions that no citizen of the wealthiest country in the history of the world should have to make. Choices like whether to go to a doctor for a nagging cold that’s only been getting worse, paying for gas, bus or transit fare to go to work, or to go to the supermarket to get groceries for your family instead of the cheaper, and less healthy, corner store or fast food restaurant down the block. There will always be unworkable trade offs made in this world.

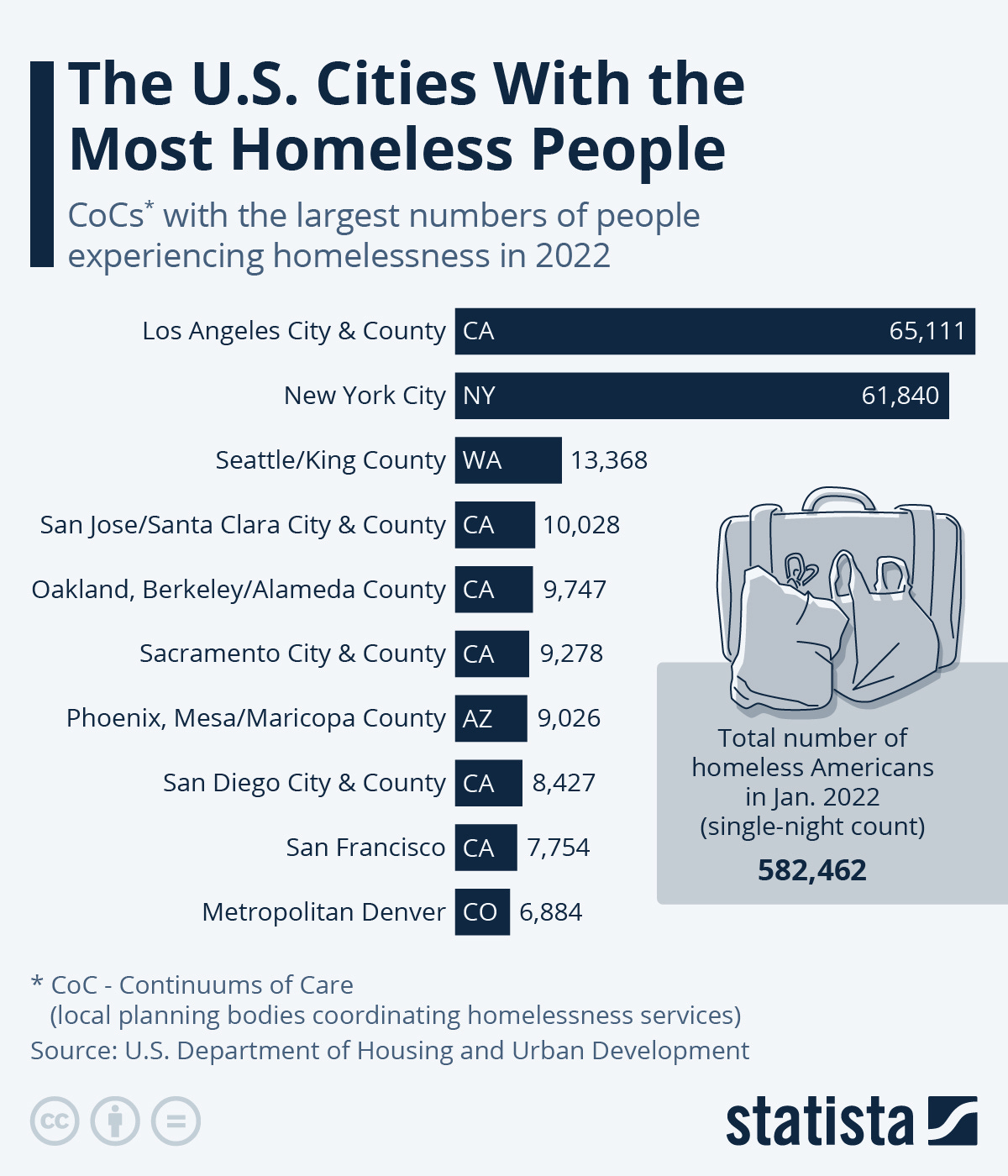

But those who have housing are the lucky ones—even those who spend nearly all of their income towards it. America is grappling with an existential homeless crisis, whose ground zero is located in progressive cities.

As of January 2022, more than 580,000 people in the US were experiencing homelessness. This goes far beyond tent encampments or individuals struggling with addiction or mental illness. Though they may be the most visible, just 17% of the homeless population are chronically homeless (unhoused for more than six months), or the type we most associate with the institution. That means more than 80% of people who suffer with homelessness do so out of sight. This may mean staying on someone’s couch for a few nights before moving on, sleeping in your car in a Walmart parking lot, or bouncing around from shelter to shelter in general state of precarity.

While the overall number of homeless people in America has trended down over the last 15 years, it has increased in our most prosperous cities. In New York, the number of families sleeping in shelters has more than doubled in the last 20 years, with the total homeless population rising commensurately. LA added 30,000 unhoused people in the last decade. In 2016, DC had a homeless rate of 124 people per 10,000, “significantly higher than the national homelessness rate of 16.9 percent”, and more than double the rate for US cities at 51%. Thankfully, DC has started to reverse the trend. How? Simple.

Homelessness is a very easy problem to solve. Definitionally, the only thing that makes someone homeless is not having a home. If they were to be given a home, voila, they would no longer be homeless, definitionally. The solution, then, is to be build more housing. We know this because the data is pretty clear. DC has been building a lot of housing, and miraculously, homelessness has dropped from its 2016 highs.

In cities that have less available housing (lower vacancy rates), and higher rents, the rate of homelessness is higher. In Homelessness Is A Housing Problem, Gregg Colburn and Clayton Page Aldern show a fairly strong correlation between homelessness, and places that have both high rent and low rates of vacancy. This makes sense. If there are fewer available homes to go around, and those few homes that are available cost more money to live in, there will inevitably be more people who cannot find housing. Should this problem persist long enough, at heightened severity, people will be forced out of the market for housing entirely. This is why Detroit, a very poor city with high vacancy rates and low rents, has a low rate of homelessness, and San Francisco, a very wealthy city with low vacancy rates and high rents, has a very high rate of homelessness.

Cities that build a lot of housing, such that housing is rendered abundant (i.e. not scarce), subsequently have higher vacancy rates as fewer people are competing for homes, and lower rents, as there isn’t a bidding process to secure a scarce good. It’s the same reason why we pay $0.50 per pound for salt today, and not a pound of gold. Salt is so abundant that we don’t need to treasure it. Sure, housing will never be as abundant as salt, and the input costs of production will never be as low, but the logic is directionally similar.

This isn’t to say that people who are homeless, or formerly homeless, don’t face challenges beyond finding shelter. Many do. But not having a stable and secure place to sleep at night exacerbates all other issues. When you marry basic and decent housing (it need not be exorbitant), with supportive systems like counseling, health care, and the psychological impact of safety, the results are remarkable.

While there have been many international studies that have shown the efficacy in combatting homelessness—Finland’s Housing First program led to a more than 70% drop in long term homelessness from 2008-2020—we don’t need to look outside of our border’s for proof of success. In one study in Denver, Permanent Supportive Housing saved the city $31,500 per participant as the formerly homeless individuals usage of police and medical resources declined precipitously with housing. For members of the case study, “Who averaged nearly eight years of homelessness each prior to entering the program, 77% of those entering the program continue to be housed in the program. More than 80% have maintained their housing for six months.” With stable housing and robust supportive services, this is a program that shows us what can be done. Or take Utah. The state reduced its chronically homeless population by more than 90% simply by providing homes for nearly 2,000 people, with limited contingencies.

If we scaled up programs like these, doubtless, fewer people would be homeless than they are today. So why don’t we do it? Part of the answer is the difficulty in effective administration. With the scale of these challenges so large, and the sums of money required to solve them so vast, like California’s $12B package to end homelessness, coordination will always be difficult. Unfortunately, there are some people who take advantage of this.

There’s an entire ecosystem that feeds off of exploiting our most vulnerable groups. While the foray of private equity firms into housing has been well documented, and widely (and mostly wrongly) speculated as the cause for our housing crisis, the arrow must also be pointed at groups who co-opt the language of progressivism towards ends that are more insidious than Wall Street scape goats. There exists a Non-Profit Industrial Complex that perpetuates the status quo with a veneer of legitimacy by using the right words, appealing to the right groups, and wearing the right team colors. From fraudsters who make millions of dollars running shelters that serve moldy food in conditions of dubious habitability, Administrators who get paid large sums to manage homelessness regardless if the absolute number of people who are homeless rises exponentially, and systems of self-dealing that rely on in-relationships to public officials and the morass of complex funding apparatuses that allow them to skate under public notice, homelessness as a business is booming. The consequences are devastating.

Far too many who work in this space don’t prioritize getting people off the street, or improving the living conditions for those they’re purporting to advocate for. It’s about personal gain while their righteousness evades suspicion. As one public official in the Northeast recently told me; Some non-profits have an incentive not to solve the issues plaguing their neighborhoods. I’ve heard from people who tell me “if we solve this problem, I won’t have a job anymore!”

This has to be rejected out of hand. There are far too many people suffering desperately for this to continue. It’s disgusting. Even worse, it wraps itself in progressive language that masquerades as trying to help, which hurts progressive causes further. Let me be clear: this is not everyone. And most people who are engaging in it might not realize that this is a problem. But the system has been structured such that it enables this level of leakage and friction, even when intentions are pure.

This is partly why we’ve struggled to build “Capital A” Affordable Housing. But unlike the shadowy world of institutionalized homelessness, very rarely does this manifest as something overtly malicious. Rather, accumulated self-interest supersedes the broader goal. In the complicated world of Affordable Housing management and development, every party takes their little piece, which, when aggregated, can lead to massive distortions that impact those we’re supposed to be helping.

In expensive coastal cities, market-rate units cost somewhere around $300,000 - $350,000 to construct, and around $275-$375 per square foot (psf). Affordable units, on the other hand, cost multiples of this. Nationally, projects financed by the Low Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) cost $480,000, and more than $700 psf. But this number varies regionally, and is brought down by rural and small town averages which have significantly lower labor and supply chain costs. In progressive cities, the numbers are far higher. In New York, Affordable units routinely cost more than $500,000. In San Francisco, the average in 2019 was $740,000, though this has risen in the last four years, as evidenced by several million-dollar plus unit projects that have recently been completed. When the market can deliver higher quality units at a third of the price, and often a third of the time, why do we stick to an inferior alternative?

Affordable Housing production suffers from a few things. First, large sums of money are required to offset the high costs of construction and continuous management. Buildings are expensive. Second, because these buildings are rented out below market (which have low returns in expensive areas as cap rates continue to hover in the 3-6% range before debt service), they’re not attractive investments. This requires them to be heavily subsidized, which leads to our third problem—there isn’t much funding available. Because of this, a lot of financing and funding must be cobbled together from disparate public and private sources, introducing many different groups into the equation. Fourth, there are many regulations on how affordable housing should be dealt with. This adds yet more costs, more confusion, more people, and much more time to a project. A market rate development that might take 18 months from genesis to completion may easily stretch to 5, 10, or even more years if it were built under Affordable mechanisms. Every additional person introduced to the project adds costs. Every additional review, or community meeting, adds time. If you’re compelled to bring a community group on board, that adds both time and money, at the expense of the community—despite the best of intentions.

To make things even more complicated, many Affordable developments have union labor or prevailing wage agreements, which introduce yet more groups with their own incentives into the mix. In New York, the city’s Independent Budget Office found that labor & wage requirements would result in an additional $80,000 in costs per unit—or 23% more than initial projections. This doesn’t pass scrutiny. Construction workers in New York are already among the highest paid in America, so it’s not like these provisions are protecting marginalized groups, as the language around these initiatives postures. An electrician making $100k a year does not need to make $120k a year at the expense of marginalized and middle classes who are being priced out of participating in our most prosperous places. She’s doing alright.

In order to deal with all of these moving parts and complexity, Non-profit developers charge very high fees, somewhere in the 10-15% of total project cost range. Despite their reputation as marauding ne'er-do-wells, this is 5-8x higher than what private developers operating in the American hyper-capitalist system would charge (2-3%).

For advocates who demand 100% Affordable or Public Housing based on a stubborn theory of the world that claims superiority, supposed morality does little to help those struggling desperately today. As we’ve seen over the last decade, it can make things much worse. People don’t need to internalize the terrors of political economy, they need somewhere to live. Do we care more about process, or outcomes? For far too many progressives, I worry it’s the former, a sort of “my way or the highway” that would rather be right than do what’s right. Besides, if one is so stubborn against the forces of capital, they should be against the forces that take 2 or 3 times as much from the most marginalized groups and keep them trapped in income-restricted housing. This is real exploitation that any progressive should be infuriated about.

The difficulty when talking about this subject is that the intentions of many of these programs come from a good place. Noble, even. Prevailing wage? It makes sense to pay hard working people well. Housing that’s affordable? No brainer! Environmental reviews to make sure we’re not further degrading our natural habitats? Who could fight against that? But when good intentions are usurped by complexity and a mismatch of reality, the best of intentions can deepen, and entrench, a negative status quo.

The push for more Affordable Housing is again a good example of this. Instead of broader upzonings to support market rate development, which we know reduces the expense of housing, those who advocate for purely Affordable Housing because they believe it will curb the predatory influences of some bad actors in the space, are causing, perhaps unwittingly, an alarming rise in segregation. Here’s how.

Because of the high costs of Affordable Housing, input prices have to be reduced wherever possible. In expensive coastal cities, one of the largest input costs is land price. The easiest way to reduce this is to build on cheaper land. Naturally, land in poorer neighborhoods is far cheaper than land in more expensive neighborhoods, whose cost is so high that it’s almost impossible to build anything other than Class A office space, high end retail or expensive apartments. And so, Non-profit and Affordable developers go where the costs of construction pencil out, which is disproportionately in poorer neighborhoods. This concentrates poverty, segregates by class, and increasingly, is segregating by race—outcomes that are as regressive as it gets.

The Furman center, a respected urban policy research institution, affirms these troubling trends in New York, stating:

“New government subsidized units targeted to low-income households were built in areas with higher Black and Hispanic population shares, higher poverty rates, and lower prices and rents than those of new units overall. In addition, new units targeted to low-income households that are suitable for families (with two or more bedrooms) were located in higher poverty census tracts than smaller units. These patterns raise concerns about whether the location of new income-restricted units is doing enough to counter patterns of economic segregation and to connect low-income children, in particular, to well-resourced neighborhoods.”

As progressives have doubled down on these policies, things have gotten worse. According to research from Pew, the share of lower-income and upper-income households living mainly among themselves increased significantly from 1980 to 2010. In New York and Philadelphia — the cities with the worst economic segregation in the country — 41% and 38% of low income households resided in majority low income neighborhoods. It’s expected that this has only increased in the last decade.

Segregating by race and by class is not progress. We’ve been working for centuries to remove the barriers that separate us and plant the seeds of prejudice. Hardening cities along identity lines only threatens to destroy much of that positive work. When you live next to people of many different faiths, races, classes, beliefs, and backgrounds, you learn we’re all more or less the same, and there’s no reason to oppose someone for a difference as unobjectionable as where they’re from. When you don’t have this opportunity, though, you distrust anyone who is different from your aligned in-group. This is partly why cities, in general, are not only more tolerant of diversity, but embrace it. When we effectuate policies that threaten this, our embrace of diversity is threatened as well. At best, it becomes a veneer where we can feel good about interacting with a person who is different than us, a superficial ephemera that does little to bring true acceptance.

This isn’t pathologizing those who struggle with poverty or find themselves in highly impoverished or segregated communities. Far from it. It’s a recognition that we have failed them. When we don’t lend a hand to those who might need a bit of help, the many problems they face can compound. This is something we’ve known for some time. In William Julius Wilson’s seminal 1987 work, The Truly Disadvantaged, he noted how high rates of unemployment and a lack of economic opportunity led to a concentration of poverty at a neighborhood level. This went a long way in explaining divergences in life outcomes between people with similar socio economic backgrounds. 20 years later, a group of researchers led by Raj Chetty validated this finding; Where you grow up matters. Upward mobility is much higher in areas where poorer families are integrated in mixed-income neighborhoods, and much lower where poverty is concentrated.

When you don’t have any role models in the neighborhood, it’s very difficult to mobilize yourself. We know the importance of representation in movies and sports, and it’s no different in professional careers. If you never see a doctor in your neighborhood, you never have a reason to think you could be one. It seems impossible, not even worth entertaining the thought of pursuing because there’s no examples of people like you who have done it.

Not only is upward mobility limited in neighborhoods of concentrated poverty, but that disadvantage can persist across generations. Building off of Wilson’s work, Patrick Sharkey has shown that multi-generational poverty can lead to reduced cognitive skills, lower family income, lower wealth, underemployment, and more anxious households. Just as a head start in a more privileged family can help a kid get a leg up and stay up, set backs passed down from parent to child can push people down, and keep them down. While this might seem obvious, having empirical data to validate this theory of the world is important as it provides irrefutable evidence of past policy failures, and a jumping off point for where we need to go in the future.

There’s an inherent distrust among progressives towards market rate solutions, and many are right to be skeptical. To an extent. There exists a long history of the private market delivering unjust outcomes, and not fully rising to meet what we demand of it. Blockbusting, failing to provide housing for marginalized groups, lower valuations for homes of people of color, and restrictive covenants prohibiting minority communities from living in private developments altogether, among many other cases, are unacceptable marks. But a lot of what people blame the private market for—mass unaffordability, suspect living conditions, environmental inequality, deprivation of opportunity—is often downstream of public policy. The market is not a sentient actor; it is a cold system that responds to the constraints placed on it by a governing body. We do not live in a libertarian state where the market runs completely unfettered. We live in a highly regulated society, and in progressive cities, we regulate too much of it.

Moreover, the legacy of public interventions is rife with abhorrent outcomes. Urban renewal, which displaced hundreds of thousands of people and tore scars through neighborhoods that continue to oppress today, was a federal policy carried out with lust by midcentury planners at a local level. The first federally backed mortgage loans were made explicitly, and exclusively, to white communities. Guidelines were crafted to further discourage the “wrong types of people” from moving into a neighborhood, in less explicit, but no less malicious, ways. When these measures were ultimately defeated, exclusionary zoning was, and continues to be, wielded as a tool of oppression. Public Housing was routinely used to enforce segregation, and ghettoized Black communities by design.

Does this mean we should lose trust in government altogether? Of course not. But it means we should focus on what it does well, and allow the private market to do what it does well, so that we can all progress forward. It’s about focusing on what each party’s comparative advantage is, and maximizing that. This is something economists have long known about, which we can modify slightly to meet our needs here. If a party is able to produce a particular good or service at a lower opportunity cost than its counter party, it should focus on that thing, not those things which it’s not so good at. If you’re a world class chef, it makes little sense for you spend your time as a tennis instructor. There’s a very high opportunity cost for that. Similarly, the government is great at providing for those who wouldn’t be considered in a market based system, focusing on supportive services, schools, big infrastructure projects, and defense priorities that might not be handled as well if things were left solely to self-interest in the market. It’s good at keeping the big picture in view, making requisite foundational investments in people and place that enable them to do what they want to do, however they want to do it. It should not be prescriptive over how people live their lives, or choose winners and losers.

No matter how much some groups may wish it were otherwise, the government is not a developer, manager, nor activist organization. It should not do things that it’s not equipped to do for the sake of adhering to a certain ideology on how the world should work outside of the constraints of our modern political economic system. That’s utopianism. A government must practicality respond to what it’s people need most. It must look at what’s working, and allow or encourage more of it. It must look at what’s not working, and do less of it. That’s the dividing line between progression and regression.

The answer to the problems many cities face is not public or private means exclusively. Putting blinders on to proclaim one system superior at the expense of the other ensures that we’ll always be missing some important piece of the pie. The solution should be whatever can reasonably be expected to progress us out of our problems. I’m sorry to say, large government responses have not done nearly enough, and verge on being negatives overall.

In far too many progressive cities, however, our officials and opting for policies they would like to see work, instead of trusting the data on what actually works. They then obstinately stick to their priors, defending their actions out of a mixture of pathos, anecdote, and righteousness, while the results get worse, and worse for all but a few. This leads to a weird dynamic where winners and losers are picked on a subjective, and arbitrary, notion of who those officials believe should be protected, and all others are either neglected or villainized.

This is something that I think needs to be addressed urgently. There exists a form of identity politic that favors a rather narrow and prescriptive community composition, as opposed to how that community is actually composed. In the past few years, there has been a hollowing out of the middle class in expensive, progressive cities, largely because they’ve simply been neglected. Through high housing costs, a resistance to address the underlying market based issues, and a lack of programs directed at those who seem to be doing well enough, we’ve failed our middle class. They’ve lost many of the gains that made our economic demography the envy of the world in the 20th century.

What’s troubling is that these are the people our communities rely on most. Teachers, firemen, nurses, and service workers generally. We cannot have a functioning society if we don’t make room for those who make it function. With homeownership out of reach in our biggest cities, foundational, middle class workers have to duke it out in the rental market. Because these groups do marginally better than arbitrary AMI thresholds that would offer them subsidized housing (and emphasis on the word marginal), they’re not protected at all. If rent is $2,300 a month for a one bedroom, it’s only “affordable” if you make more than $92,000 a year. In many expensive cities, $2,300 for a one bedroom would be a steal. If you make $50,000 a year, you wouldn’t be considered marginalized, and would likely not be protected by subsidy. But, as this example has shown, you’d really struggle to make ends meet, and that’s before food, transportation and medical costs, to say nothing of actually getting to enjoy your life, are factored in.

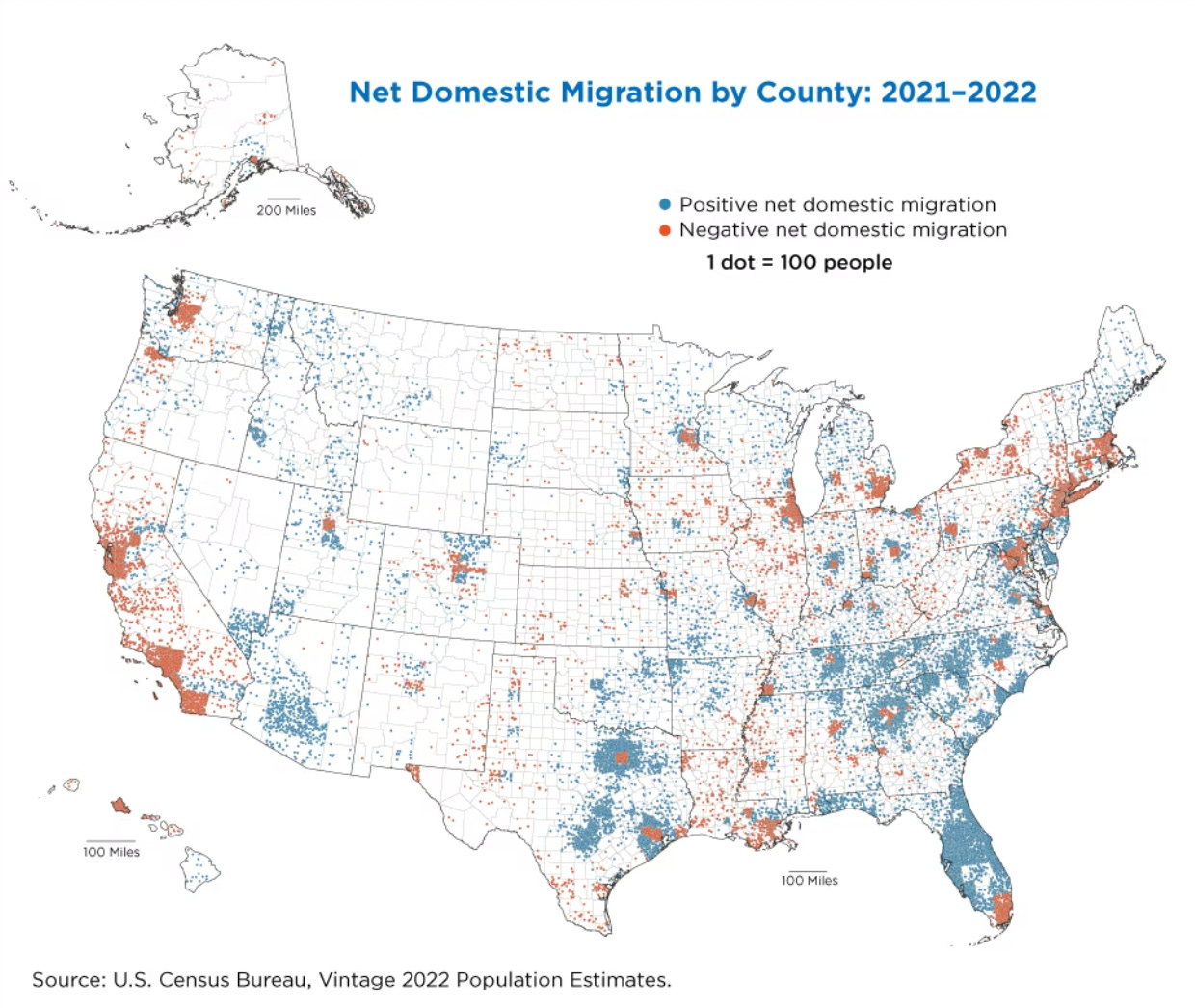

Our response to this has effectively been to force people into soul-crushing and environmentally destructive super-commuting patterns somewhere they can afford to live within the metropolitan area, or make them move out entirely. Indeed, on net, millions more people have moved out of large progressive metro areas in just the last two years than have moved in. In the New York, San Francisco, and LA metro areas alone more than a million people, on net, left from 2019 to 2021. Between 2021 and 2022, 143,000 more people left Los Angeles County than moved there, down from 195,000 net people who left the year before.

Where have they been moving? Overwhelmingly, to red states that are more than happy to accept them. These places have far less restrictive zoning and planning codes, and have thus been building significantly more housing than their blue counterparts, which has led to lower costs. If you’re a hardworking lower or middle class family who just wants to be able to afford a place to live and enjoy life without the vice grips of cost of living squeezing you out entirely, you should be able to move to do so if the place you currently live in is not willing to give you that opportunity. It is an entirely rational decision that millions of people have rationally come to. When a new (ish) starter home in an area close to many amenities and jobs costs $340k in Houston, and the equivalent in San Francisco is $1.2m, the choice is obvious. It becomes even more clear when taxes are lower, economic development is higher, and where it’s easier to start and run a business (the backbone of the American economy).

While the states that are welcoming the most people are red, as David Brooks notes, most of the population growth is coming in cities that are more blue, creating a red-blue gradient.

“Republicans at the state level provide the general business climate, but Democrats at the local level influence the schools, provide many social services and create a civic atmosphere that welcomes diversity and attracts highly educated workers.”

These are places where one ideology cannot prevail. Both parties have to work hard together, putting their prejudices aside, to create better places for everyone. There’s no room for complacency. This is not the case in echo chambers of conservative, or progressive areas.

It’s no wonder why so many people are opting to leave these sort of homogenous places. Sadly, public officials have coped with these trends with flawed logic that verges on zealotry. If people don’t stay here, they reason, they must be republicans or morally compromised in some way. People who hate cities and diversity. That many of the people who are leaving progressive cities are minority groups, working class families, and members of their own team (!) is completely lost of these officials. The accelerated purpling of red states in the last few years can be explained in large part due to blue cities failing their own constituents.

Instead of working towards solving the issues that plague their constituents and getting competitive with their red state rivals, it seems as though they’d rather admonish regular people for making decisions that make the most sense for their families. There is a sort of hatred directed towards those who live in, or move to these places (a hatred that cuts both ways, to be sure). It manifests in a divisiveness as ugly as that which they claim the other side is. If you move to Texas, or Tennessee, or Florida, you must be some ideologue or bigot, they reason. Totally missing the underlying motivations for why someone would want to do this, as they only see the world through a binary ideological system; you’re either with us, or against us.

This is an insane way to respond to your own failures, especially for an ideological movement that prides itself on representing people of all classes, races, beliefs, and orientations. To blame those who leave because of your own failed policies, instead of working to solve them, just so you don’t have to cede the moral high ground and accept you were wrong, is sheer lunacy, and utterly disgraceful. It’s time to look in the mirror.

There is a sort of moral elitism at play as well. Oh, I could never go to a red state. Those people are worse than us. This not only poisons the well for our country even more, pitting us against them in a nonsensical battle which ignores that we’re all the kind of the same and want the same things for our lives, but it’s hypocritical. We’d do the same exact thing if we weren’t fortunate enough to be born in the places and positions we were. Progressives are understandably skeptical of the notion that people can pull themselves up by their bootstraps (without help, at the very least), but we’re effectively prohibiting people from even trying shoes on, while the cities across the street are offering brand new nike’s at a fraction of the cost of our beaten up fila’s.

When people do choose to stay—not an easy decision—progressive governments are focusing more on social issues than fundamental quality of life issues. That’s a problem. I’m someone who proudly supports nearly all progressive social causes. But, they cannot supersede the foundations of city governance. We cannot ascend the hierarchy of needs to more delicate issues until we’ve solved basic things like housing, education, quality infrastructure, access to healthy food, and public safety.

Casually dismissing away crime waves, murders, assaults, and mass psychological fragility as…pittances, or worse, chiding those who are concerned about them, is outrageous. It’s astounding that progressive leaders have managed to make those who feel concerned out to be some kind of bad actors, for simply calling a spade a spade, and demanding better. It should not be a political statement to say that getting assaulted on the street by a stranger is bad, actually.

This is not a winning game plan, and it’s infuriating this is the position so many progressives have chosen to settle on. The response should not be to dunk on people for a few likes on twitter, but rather, listen to their concerns—they are, after all, your constituents—and work to progress forward.

This sort of poor governance is chronically destructive. It not only sends a message that a place can’t do the simple things right, but that it has poor prospects for the future. If a city doesn’t care about its existing residents, it can’t very well accommodate new ones. Instead of making their livelihood in New York, or LA, or San Francisco, or Boston, or Seattle, would be residents will move elsewhere, delivering to that place their unique talents, culture, presence and economic contributions. While this will doubtless deprive progressive cities of their next generation of artists, visionaries, builders, and thinkers who have for so long delivered invaluable cultural capital and global goodwill, more importantly, it will deter the everyday people who make a city run. They’ll move to cheaper housing, as amenities do little good if one can’t afford them.

I’ve had the good fortune to travel much of this country over the last few years for work, and have seen a lot of different kinds of places. The people are roughly the same wherever one goes, but the spirit is wholly different. I’ve felt significantly more hope and optimism in places like Texas, Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina, than in New York, LA, or San Francisco and DC. This may be because people aren’t filled with existential dread about how to afford rent from month to month, and have time to spend with their friends and family, doing whatever it is they like to do. As a New Yorker, I wish it didn’t feel like Texas or Florida were places where the future felt possible, and the city felt zapped of promise, but I can’t say it doesn’t feel like that. As a long lover of Los Angeles and San Francisco, I wish I didn’t feel as though they’ve failed in some profound ways. But I can’t ignore the reality, the data, or the personal anecdotes from dozens of opportunists who have flocked from around the world to make sunbelt cities the envy of all economic development and quality of life surveys.

Does not this make public officials angry? That our greatest cities are content to close up shop, fall from grace, and not continue the wonderful stories they’ve woven for centuries? We have to wake up! But it seems all we’re doing is talking a lot about how the world should be, and signaling what we would like to believe to be true, without doing very much.

There is perhaps no better symbol for this than the “In This House We Believe” sign. It’s a fantastic message of the things we want. But it doesn’t do anything. It might actually hamper action because it gives people a false impression that they’ve done their part. If we do believe in the platitudes of the sign, what do some of those words really mean?

Black Lives Matter

If we believe that black lives matter, we can’t concentrate cities by race and then deprive those communities of opportunity. We need to invest back into black communities, in ways that actually benefit them. Instead of railing against any level of change as gentrification, we need to accept that some neighborhoods do need some improvements, that renovating run down properties, stopping crime, and having grocery stores where they previously didn’t exist are good things that people in these areas deserve.

There will doubtless be concerns about displacement; valid concerns. Cities can introduce anti-displacement measures such as tenant protections for people who have lived in a building for 5 years or more, and stronger protections for those who have lived in a building for longer, should they choose to stay. But we can’t tie people to communities because that’s where they’ve lived for some period of time, or because we believe certain types of people should live in certain types of places.

If we believe that black lives matter, we should unlock zoning codes to allow black communities to develop their neighborhoods themselves, and build wealth along the way. This is clearly superior to the current system where it’s being drained away by amorphous, institutionalized corporations and non-profits who throw up large towers that take away the core elements of what makes a community feel like a community. We need to stop disincentivizing people from finding opportunity through upwards economic mobilization because they’re afraid of losing their income restricted apartment. We just need to build enough such that everyone has enough, and can feel comfortable to pursue whatever it is they want to pursue.

No Human Is Illegal

If we believe that no human is illegal, we have to build housing for all who need it, free of qualifier or caveat. This means reigning in exclusionary zoning whose original sin remains its modus operandi—excluding those of lesser means or different backgrounds from participating in a neighborhood. It means rejecting the lobbying from wealthy homeowners who live in communities that haven’t done their fair share to ensure all can have a place at the table—the types of places that have these signs up in their communities. Places like Westchester, Northwest DC, the West Side of LA, San Mateo and Marin Counties. They have a lot to answer for.

It means holding truth to power, and calling out the hypocrisies of those who damage this cause. Robert Reich, one of the best known public progressives in America, is perhaps unaware of his cognitive dissonance on this front. While he has urged Wall Street executives to build low income housing, he apparently believes he’s above doing the same in his own community, passionately fighting against the replacement of a dilapidated home in favor of 10 new apartment units (which would have included affordable housing), writing, “Development for the sake of development makes no sense when it imposes social costs like this." Really? The social costs of people living in tents or spending 70% of their income on housing don’t outweigh the social costs of demolishing a dilapidated building in your own neighborhood?

If we believe that no human is illegal, we can no longer artificially reduce the amount of places for people to legally live, or leave the provision of that housing to dumb luck. We have to end housing lotteries, which treats basic habitation as a prize. Since 2013, there have been 25 million unique applications for 40,000 lottery eligible apartments in New York, for a 1 in 625 chance of securing a home. Applicants wait years, verging on decades, just for the hope that their name might be called to secure a quality place to live. This is insidious, and by design. The Affordable and Public Housing apparatus cannot create the amount of homes that we need, but it is continuously looked at by progressives as the only viable way of moving forward.

We can’t be ignorant of the costs of construction, which are real and high. We cannot merely hope to build ourselves out of the housing crisis, we have to have solutions grounded in reality that actually lead to homes getting built. Any conversation that dismisses costs, competency, or consequences should not be entertained.

We have to stop saying things like “I support affordable housing, or homeless shelters, just not here.”, and reform that to be, “I support housing of all kinds in all places.” But it’s not enough just to build. We have to build well.

If we believe that no human is illegal, we have to open our cities up to the refuges and immigrants from around the world who so desperately need a place to take them in. What’s more of a no brainer than this? The benefits are myriad. Immigrants start more businesses and create more jobs than they take, pay an outsized share in taxes (~30% of all tax dollars despite being less than 14% of the population), and bring invaluable cultural richness that makes the fabric of our society better. Of course, progressives agree with all of this and theoretically want more immigrants and refugees to come to the US. But these beliefs have to align with our actions, and they simply have not in recent years. We have to enable the creation of places where people of lesser means trying to make it in America can safely and comfortably exist, not pile into unlit and overcrowded basements with horrifying conditions. Is this what we stand for? Forcing those who have risked everything to contribute to our society into dark warrens of danger, precarity, and neglect? Shame on us.

If we believe that no human is illegal, we will have to build permanent supportive housing in the fabric of our communities for formerly homeless individuals, not concentrate it in out of the way neighborhoods, and further ostracize those who have fallen on hard times. It is not progressive to let people sleep in their cars, navigate brutal shelter conditions with young children, or be forced out on the streets and struggle with mental illness or addiction.

If we believe that no human is illegal, let’s act like it.

Science Is Real

Progressives pride ourselves on trusting the data, and believing that science is real. We respond to empirical findings, basing our worldview on an evolving body of research that allows us to trudge forward in the murky waters of doubt in the pursuit of truth and knowledge. But somehow, progressives refuse to hold this same scrutiny up to the housing market, or public safety, or, yes, climate change. Or any number of other issues that have been adjudged to be settled matters, heretical to the prevailing orthodoxy. We cannot distort data to make it do things we would like it to do, we can only follow where it leads and base our policy around that.

In the last few years, there has been something of a consensus from housing economists that building more housing reduces the cost of housing. New construction has been found to reduce rents by 5–7% in a neighborhood, as more supply reduces competition over homes. What’s more, for every 100 new market rate apartments built, 70 middle-income apartments open up for people lower down the chain of housing, as each new unit of housing ripples outwards in a chain effect where the wealthiest people move into the newest units, and everyone else moves up. In a study spanning 1970-2000 of California’s Pacific Coast, which looked at the impact of a 1976 coastal boundary zone initiative that restricted the amount of housing that could be built, Kahn et. al found that home prices rose by 25% more than unrestricted areas in the same region, a trend that has accelerated in the last two decades. In Auckland, New Zealand, New York, Portland, Los Angeles, and Houston, signifiant amounts of new housing supply were introduced after upzonings or liberalizations of planning regulations, offsetting or reducing upward rent pressure.

In a study of 180 upzoning and downzoning policies in more than 1,000 municipalities, “reforms loosening restrictions {were} associated with a significant, 0.8 percent increase in citywide housing supply at least 3 years post–reform”. That increase might sound small, but it’s not. It would account for nearly half of the new dwelling units produced in New York City in 2021, a huge, huge number.

These findings should be intuitive. When you provide more of a good, prices reduce. When you restrict supply of that good, prices inflate. This is the basic logic behind why exclusive sneakers that are manufactured for a just couple of dollars sell for many hundreds, or why apples are so cheap at the supermarket. It is a simple issue of supply and demand, a basic economic principle we’ve known about for hundreds of years. While the contemporary progressive may shudder at this language, they can’t ignore it.

If we say we trust the experts, these are the experts. We can’t be so ideologically predisposed to one outcome that we reject when all of the data tells us another route is superior. Contrary to what many think, fighting against market-rate housing does not stick it to the capitalists. It damns the most marginalized who have no other way to secure scarce housing. We have put what is right over wanting to be right.

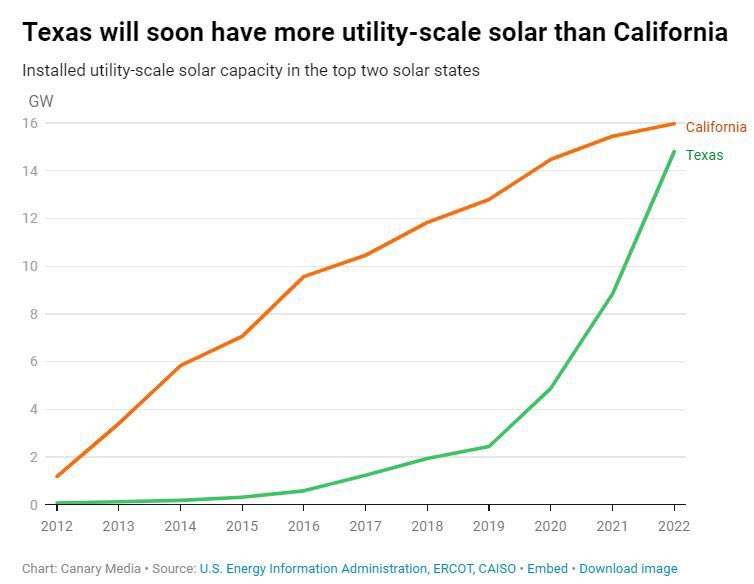

Over the last decade, a similar story has played out with environmental groups, and those who have co-opted environmental language to masque their personal grievances. Climate change is one of the top issues on the progressive docket. While increased capacity of renewable energies, adoption of non-fossil fuel vehicles, recycling materials that can be reused, and the conservation of resources generally have been touted as important contributions in reducing our impact on a changing climate, the largest greenhouse gas emissions savings will come from changing our development patterns to support more infill development. That’s according to the IPCC, the experts who are tasked with our global response to climate change.

These reductions don’t come from switching to electrically powered cars from their internal combustion cousins, but by not using cars at all. The more that we can walk or bike to carry out most of our daily needs, the less emissions there will be generally. Even if everyone were to drive EVs, electric grids would have to be 100% run on renewable energies. They are not. It’s currently about 17%. Though this proportion is growing, we still have far to go. And even if we achieved 100% renewable energy generation for our grid, but continued driving everywhere, we would still generate significant emissions from the production and transportation of these vehicles, and driving over asphalt roads. Stormwater runoff would remain high, urban heat island effects would deepen (requiring more energy), and utilities and water would continue to be pumped across great distances at low density, which is neither efficient nor sustainable.

But, if we gradually increase the density of already built up-areas, more people get to share resources, leading to far fewer emissions per person. If we demolish a two story building that housed 4 people, and construct a 5 story building to house 40, that’s 10x efficiency gain. Those 40 people can use the same roads, utilities, and public amenities that the 4 people did, and in the event that we need to upgrade capacity, there will be sufficient tax dollars to pay for it, unlike in more sprawling areas. This is why, despite all appearances to the contrary, New York is the most sustainable city in America on an emissions per household basis, and leafy exurbs are the least sustainable. Just because something looks green, does not mean it is.

In light of this, it’s concerning that so many progressives in places like San Francisco, Manhattan, and San Diego use environmental reviews as a tool to kill new development within the city, that could actually lead to more climate resiliency. This guise not only delegitimizes the importance of environmental review in some contexts, but it makes the other great challenges of our cities—high housing costs, declining tax revenues, lack of opportunity and economic mobility—worse. The absurdity of feigning outrage when a mid rise building rises in place of a parking lot, garage, or low rise building out of fear for the environment, when everything else around that lot is a mid rise apartment building or otherwise built up area, is staggering. There is no risk of the environment worsening because a new apartment building goes up in the heart of San Francisco. Maybe 150 years ago, but not today.

The absurdity continues as these same people don’t register any level of concern for the many millions of acres of natural land that are cleared as an inevitable result of no new housing being built in already built up areas. An asphalt parking lot turning to an apartment building? Horrifying. 1,000 acres paved over and even more land stamped down to run utilities and other services out to the new development? *crickets*

This is a brazen and foolish bastardization of well intentioned laws to fulfill narrow personal interests hiding behind a veneer of the right esoteric phrases and appeals to emotion. What’s worse, when we don’t accommodate new development in relatively climate resilient places like Seattle or San Francisco, people move to decidedly unsustainable places, like Nevada or Arizona, where they’re guaranteed to produce 2-3x more carbon emissions because the infrastructure is entirely car dependent. When you factor in rising temperatures and diminishing water reserves, the situation gets worse and worse.

Progressive areas have used “environmental review” laws to entrench oil & gas interests, while places that could hardly be considered progressive are charging full speed ahead building renewables and housing (though less sustainably) at much greater rates. We must do better.

The funny thing about reviews is that many of them were created with the goal of leading to bureaucratic delays. This is a tactic that has long been used by republicans to thwart initiatives they disagree with, as Nicholas Bagley writes in his paper, The Procedure Feitsh,

“Conservative reform proposals travel under an array of names and acronyms, but they embrace a common tactic: They stack procedure on procedure to create a thicket so dense that agencies will either struggle to act or give up before they start…

If new administrative procedures can be used to advance a libertarian agenda, might not relaxing existing administrative constraints advance progressive ones?”

For progressive who see themselves in a holy war against the other side, the processes they’re employing have done the bidding of their enemies, for many decades, with increasing frequency!

Progressive cities have been telling themselves a myth for the last 20 years. But that’s not necessarily a problem. Self-mythologizing can be a good thing. It can form the basis of community spirit, identity, local pride, and the pursuit of virtue. It becomes a problem when it’s used as a masque to deflect from real challenges, and as a cudgel against supposed enemies of the orthodoxy. When the myths we tell ourselves transcend the realm of spirit to inform policy, of which there is rarely a one-to-one relationship, dangerous consequences may arise. The world gets reduced down to identity and binary poles. Black versus white. Good versus evil. Progressive versus Conservative. Capitalism versus Socialist. Right versus wrong. We pick winners and losers in this world, governing not for the entirety of a constituency, but selected people we most personally align with. That’s not the job of government. The real world, of course, doesn’t work this way. There exists a lot of gray. When we fail to acknowledge that, common cause is thrown by the wayside, and those seeking common sense are deemed heretics.

Progressive cities have forgotten what progressivism really means, opting for ideology at the expense of the people they’re meant to serve. If we genuinely care about the most marginalized members of our society, we need to actually help them with proven solutions. Not use college-rhetoric and ideology that don’t materialize in reality, no matter how much we wish it were so. This means sorting through the morass of idealized interventions and trusting what experts, data, and science tell us. Only then can we move towards living up to the values we embody by progressing the status quo beyond the many challenges we face today.

When one looks back in history, no one’s hands come out as clean as binary ideological positions would hold. That form of tribalism has to be left to the past, as it’s impacting real people today. We have to focus on what works, and progress forward. If it fails, we need to be willing to embrace creative solutions, not just speak soft platitudes or place a sign on our lawn or in our window. That’s not action. We need to level with people, and stop lumping them together a part of a group for whom we think they should be, and instead listen to them as individuals who have autonomy over there life.

Prescribing policies for everyone that are narrowly tailored to the few guarantees outcomes that are antithetical to our broad goals. Ironically, the policies progressive cities have adopted in the hope of protecting the marginalized and working classes have backfired, because they don’t truly respond to what these groups need. By villainizing capitalism and corporations who create jobs and allow people to mobilize themselves upwards, and neglecting the middle classes entirely, a permanent underclass that is oppressed through infantilizing policy is created. Progressive policies have spoken to the position of where people are today, but not where they want to go.

By allowing housing prices to run up so high such that only the most well off or most willing to spend all of their income can afford to live in cities, segregating marginalized groups out of the way in “Capital A” Affordable Housing with little economic opportunity, refusing to address valid concerns on crime and quality of life issues for fear of stigmatization, and not investing sufficiently in a rising tide that can lift all boats within a city, progressives are failing at their one job.

You can only say things that your actions invalidate so many times before people stop believing you, or you’re labeled a hypocrite. Those on the left seem more concerned with how they might appear than what they actually do. It’s about posturing, not progress. As a progressive, I can’t stand for that. Living up to our values means opening up our most productive places for all, not restricting them and subjugating those who live within them, but using language that makes ourselves feel better.

The way to do this is to build such that we raise everyone up, not conserve the status quo for a few, while it worsens for the many. Ezra Klein, one of the more prominent progressive thinkers, has been advocating for a “liberalism that builds”, which I think is the exact way to move forward. Klein has been a loud critic from within, writing,

“Scratch the failures of modern Democratic governance, particularly in blue states, and you’ll typically find that the market didn’t provide what we needed and government either didn’t step in or made the problem worse through neglect or overregulation.

We need to build more homes, trains, clean energy, research centers, disease surveillance. And we need to do it faster and cheaper. At the national level, much can be blamed on Republican obstruction and the filibuster. But that’s not always true in New York or California or Oregon. It is too slow and too costly to build even where Republicans are weak — perhaps especially where they are weak.

This is where the liberal vision too often averts its gaze. If anything, the critiques made of public action a generation ago have more force today. Do we have a government capable of building? The answer, too often, is no. What we have is a government that is extremely good at making building difficult.”

He’s more recently released a piece about everything-bagel liberalism, which gets at a similar point as the one I’ve been writing here (this should serve as motivation for me to write faster, as this article is 6 weeks in the making, but I digress). Klein notes that liberal governments aren’t constructed to face the challenges we do now. Instead of thinking critically through the ramifications of certain policies, there is more of a “vibes” implementation over doing what is right.

“One problem liberals are facing at every level where they govern is that they often add too much. They do so with good intentions and then lament their poor results”

We can no longer sit idly by and lament poor results. We need to marry theory with reality in the service of creating a better society for everyone. It’s well past time we take measures that allow us to live up to our values, and damn the politics. If you care about making our world a better place for all, we have precious little time to worry about the appearances.

Coby Lefkowitz is a real estate developer, writer, and thought leader in the world of urban planning and development. He recently published the book Building Optimism, explaining why our world looks the way it does, and how to make it better. Purchase your copy, via the link.

Excellent article!

But I want to push back on something. Especially in a blog called “southern urbanism” that seems to have nothing good to say about the south beyond it gives cheap housing for New Yorkers to move to.

1) interaction with people of other races and classes tends to decrease trust and opinion of those groups. I know the opposite was thought to us all growing up, but that’s because we lived in price segregated communities where everyone was like us. We could believe the propaganda because there was no evidence against it.

When I moved to the city and was around underclass dysfunction. When I got my first job as a teenager and was around “the working class”. Man…those people are terrible.

If the lynchpin of your idea is that we need housing policy to mix the groups, it’s not going to work. Everyone up and down the class ladder wants to interact with people like themselves. Isolating by price is natural and healthy.

All you can do is build a lot so prices come down for each social class. So that upper middle class people who can’t buy luxury condos that don’t exist have to try to gentrify a bad neighborhood and hold off on having kids until it’s “turned” and they feel safe sending then to the local school. With “safe” being determined by when enough of the old residents are priced out.

2) problems in lower class neighborhoods can only be fixed directly. Not by flooding upper class neighborhoods with hoodlums. You need sound policing and better order in schools. Blue states seem unable to provide these things. Red states do better. I think this is likely structural.

3) southern states have done the most pro housing thing in the world, universal school vouchers.

NYC spends $40k per kid per year on schools where your kid would get beat up. Naturally, upper middle class people defend the few zip codes where they can get a “free” education for their children where they don’t get best up. Tying education to property ownership makes “upzoning” a complete non starter.

Red states severed the link between schooling and property, which makes it easier to build property because it doesn’t affect your kids schooling.

4) there was a theory that blue states severed people moving to red states would turn them blue.

But the data doesn’t show that. People moving to red states are as much political refugees as economic ones, and they are increasingly higher income.

They move to cities because that’s where the jobs are, but they generally settle in the suburbs in giant SFH HOA planned communities to raise their large families.

I’m a Covid refugee that moved to Florida once they passed school vouchers.