Who Killed the City?

To build better communities, we must fix the lasting effects of the historical policies that regulate them.

Written By Vaneesha Patel

This article is Part Three of a series on the forces, processes, and regulations that harm good citybuilding.

Most Americans want to live in inclusive communities. So what’s stopping them? The short answer is regulatory regimes. The long answer is the history behind them. The people who build cities can create the neighborhoods people want, but only if harmful laws of the past are truly remedied. To do that, we need to look at policies that may no longer be active but still have palpable effects on our cities.

While many processes, stakeholders, and institutions play a role in how our cities are built today, there is arguably no bigger influence on our cities than our history. For centuries, policymakers have made decisions that have forever altered the fabric of American cities, and the implications of such decisions are still apparent. As the Pew Research Center has noted: “In the decades since the Fair Housing Act of 1968, the extent and nature of discrimination have changed, but its imprint remains visible in many cities; it continues to influence choices about where people of different races, ethnicities, and income live.” That quote is from 2008, and not much has changed. Let’s recall a few of the major offenders.

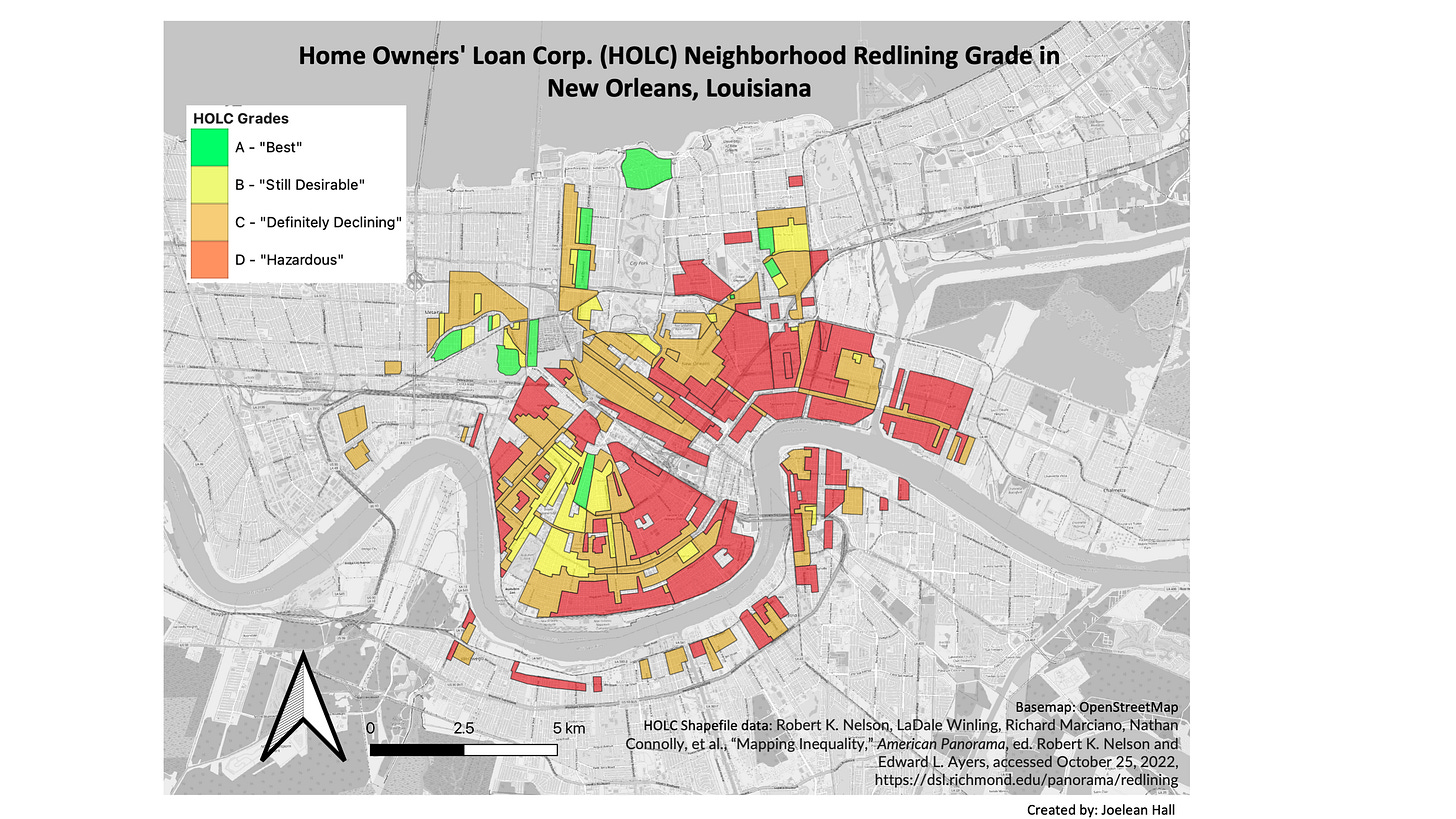

Redlining

In the early 1900s, redlining resulted in underinvestment in predominantly Black and immigrant neighborhoods. This led to a lack of infrastructure investment and new development in such areas, creating large disparities between neighborhoods that may have only been a couple of blocks apart. Today, areas that had been formally redlined consist of older housing stock and receive less in rent revenue. In addition, previously redlined areas also face worse health outcomes.

Urban renewal

In the 1950s, urban renewal swept America. With a promise of bringing better communities, “run-down” areas were demolished and replaced with new developments. In the process, vibrant neighborhoods were ripped apart and displaced. A prime example of this was Mecca Flats in Chicago. Once home to a lively community of artists, white-collar laborers, and musicians, this predominantly black community within a building was replaced with the Illinois Institute for Technology’s Crown Hall.

Urban highways

The highway boom of the 1950s also changed the American landscape. With heavy investments in highway construction and expansion, communities were ripped apart as people were forced to become more reliant on automobiles. In Austin, that decade saw East Avenue cleared to make way for the construction of 1-35. A place that had been home to predominantly ethnic communities was demolished in favor of a highway, a decision whose effects were compounded by the implementation of additional discriminatory policies that led to even worse outcomes for people of color.

The impact of history on our cities goes beyond physical infrastructure and development. It also extends to the cultural and social fabric of a city, including patterns of discrimination and exclusion that still affect communities today—ones that continue to impact our built environment. It’s a vicious cycle. Recognizing and addressing these issues is a crucial step toward creating more equitable and inclusive cities that benefit all residents. So when we ask ourselves, “Who killed the city?”, there is not necessarily one thing to blame. However, as work continues to build good cities, we must understand that the way we build occurs within the context of the past. The more that citybuilders do that, the more they can get out from under the thumb of destructive regulations.

Vaneesha Patel is the Spring 2023 Mencken Publishing Fellow on Urban Development.