POLICY | Planning Isn’t Perfect

5 lessons I’ve learned in a few years on a municipal planning commission.

Written By Marshall Hines

I’ve spent the last six years serving on my fast-growing town’s Planning and Zoning Commission. I’ve gotten the chance to review more zoning cases than I can count, been involved in two major Comprehensive Planning efforts, and seen many thoughtful ordinances passed and just as many bad ideas codified. Here are a few lessons I’ve learned.

1 – The Devil is in the details.

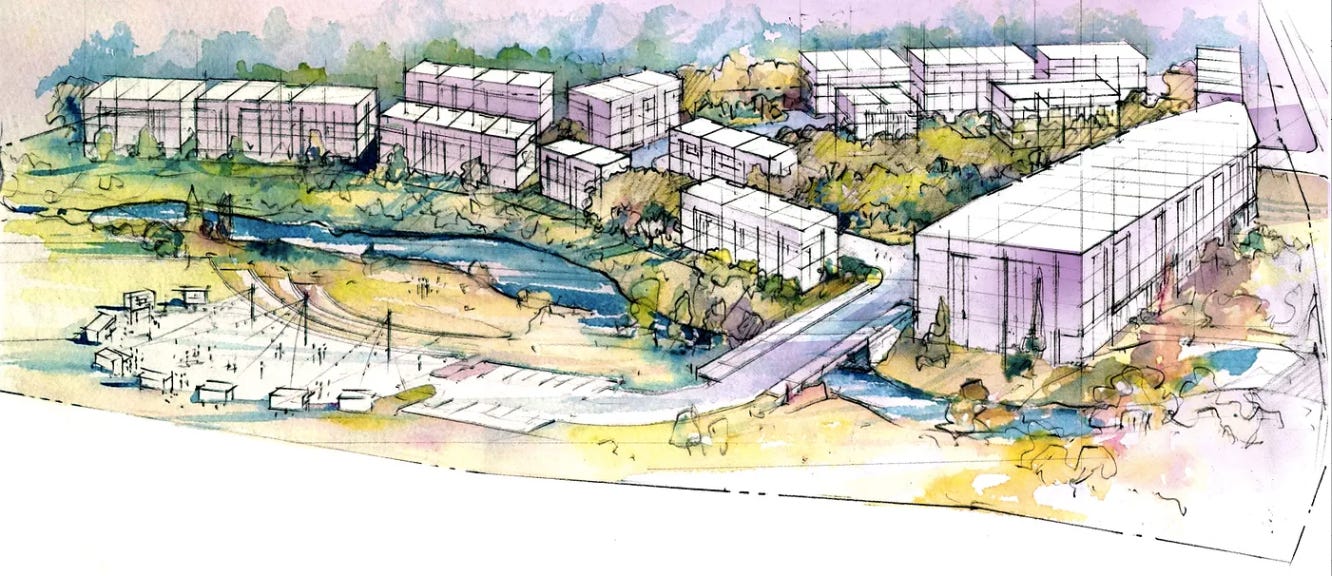

Cliché or not, it’s the truth. Whether it’s a requested zoning change, a variance case, or a text amendment to an existing code, the way that these changes affect your built world usually comes down to small details. As an example—here is a rendering of a project that we saw for a “mixed-use” development:

And here is what it looks like built:

Why don’t these images look all that similar? Because we don’t zone based on renderings. The building size, footprint, and placement are identical to the zoning language. What was not in the zoning? How these buildings interfaced with the public realm, and how this development implements its connections to surrounding properties. It’s easy to be swayed by pretty pictures, but it’s important to separate what the renders show from what is actually required by the zoning language.

And by the way, where is that super cool food truck park? Well, it doesn’t exist because it would reside on city-owned property unrelated to this actual project. This was obvious when the case was reviewed—but some commissioners were swayed just by the idea of a mythical something “fun” being in town.

2 – Everything we build has to be maintained.

Every road, bridge, rail line, stormwater system, electrical substation, and traffic signal has to be maintained in perpetuity. That is expensive.

Who pays to maintain these things? We do, through services fees or property and sales taxes, and the maintenance bills come long after the initial buildout starts. That means it’s easy to find ourselves in a financially unsustainable position at a time far removed from the infrastructure being installed.

Another way to put this is to recognize that we, the citizens of our cities and towns, are “developers” just as much as the company building a strip mall or neighborhood full of houses. Our town builds/develops the roads and traffic signals and is responsible for maintaining them. We, the citizens, pay the taxes that pay for that. Every piece of built infrastructure has a cost associated with it, both immediately and over its lifetime, to keep it running correctly.

When a company builds, they consider how much every decision they are making will cost, both short and long term. A residential builder will not build 20 extra houses “for future growth” if they aren’t certain that there are buyers ready to buy them. And why would they? Maintaining an empty house doesn’t make financial sense.

Thoughtful decisions regarding infrastructure improvements can be used to generate wealth for our community, but careless building simply creates a liability that the existing community foots the bill for. To expand the metaphor, building a road “for future growth” is shortsighted for a city, just like the extra houses were for the homebuilder.

3 – Land is a finite resource.

Obvious? Not as much as you’d think. Land use planning is as much about determining how we don’t use land as it is about directing how the built environment inhabits it.

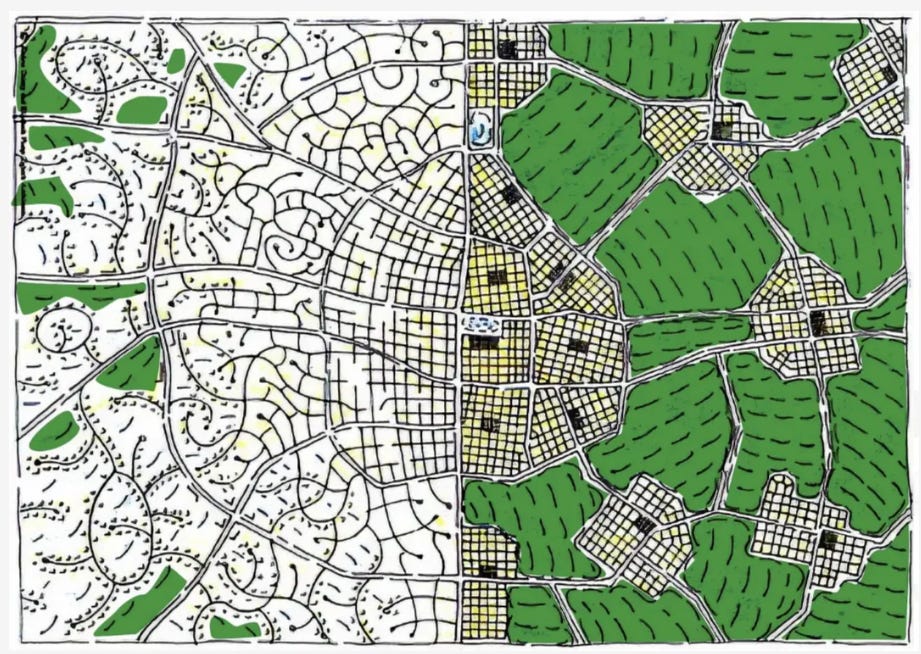

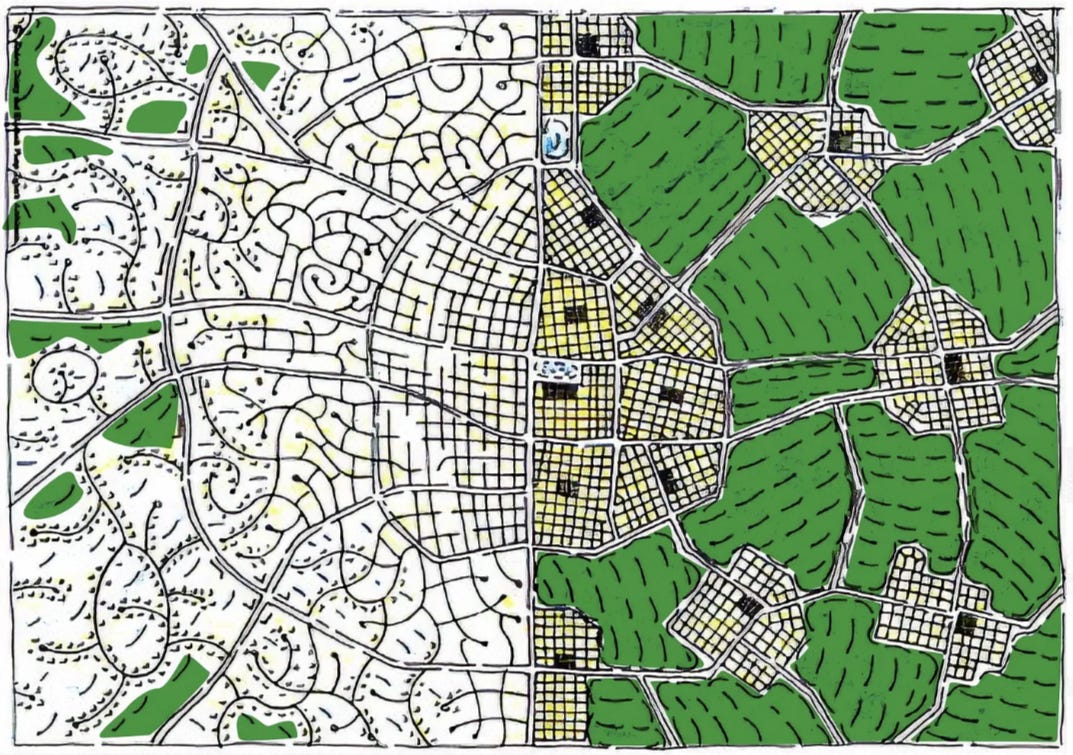

Humans universally like natural, open places. In the decades after World War II, Americans were sold the promise of their own little slice of nature in the form of a rolling and lush lawn. This built us the suburban ranch house and the neighborhoods that much of Gen X and the majority of Millennials grew up in. When everyone lives on a quarter acre, you run through your finite land more quickly, and building moves ever more quickly out.

As a result, the idea of bringing people closer together on less land in a denser pattern of development feels anathema to many people who have only experienced the curving suburban streets and cul-de-sacs of the past 60 years. But doing so brings with it some incredible benefits. Most people living reasonably close to a major city will have access to a large Cadillac park. This is the jewel of the city—it’s the place everyone brags on and pines for when they are away from home. These places are smaller than you think. Take a look next time you’re browsing around Google Maps: We can have a network of large, undisturbed park spaces if we are willing to build our homes and communities in a more compact way.

4 – The Planning Professionals have gotten it wrong, many times over.

We should feel comfortable enough as citizens to question the wisdom of the professionals. There is a long history of boneheaded decision-making because a small group of people decided it was “proper.” The list is long, but let’s hit a few big ones:

Euclidean zoning categorizes every use and separates each one, forcing us into our cars for even the most basic of needs.

Restrictive covenants were used originally to racially segregate our communities and apply the thinking of previous owners to the future of a place.

Highway building through the center of communities broke up the connected nature of cities in the service of moving people “through” your town as quickly as possible.

Disposable architecture that no one loves and thus no one wants to maintain.

Why did many of these things take hold so fervently? I’d argue that most often, it was because the people who inhabit and are most closely connected to their cities and towns were removed from the decision-making process and told that the “professionals” knew better.

5 – There are lots of places to learn from and lots of people who want to help.

In the Information Age, we can learn a lot from the mistakes and successes of the communities around us. And we can learn a lot from the iterative improvements we have made around the world throughout recorded history. Here are a few places that I have found to be good resources for learning about how and why we build cities the way we do:

Ultimately, we all have to take part in making our communities better, healthier, more financially resilient places. If you try to do this by serving on your local planning commission, then remember that you can bring something novel and unique to the job: your personal experience and your connection to the place you live.

Marshall Hines is a Creative Director focused on Urban Design and Placemaking. Follow Marshall at @marshallhines

NOTES

This piece was originally posted on Medium in 2021.

Images 2-7 via the author.