JACOBS | What’s Next for the Sidewalk Ballet?

Despite widespread acceptance of her beliefs, Jane Jacobs failed to create the world she coveted.

Written By Aaron Lubeck

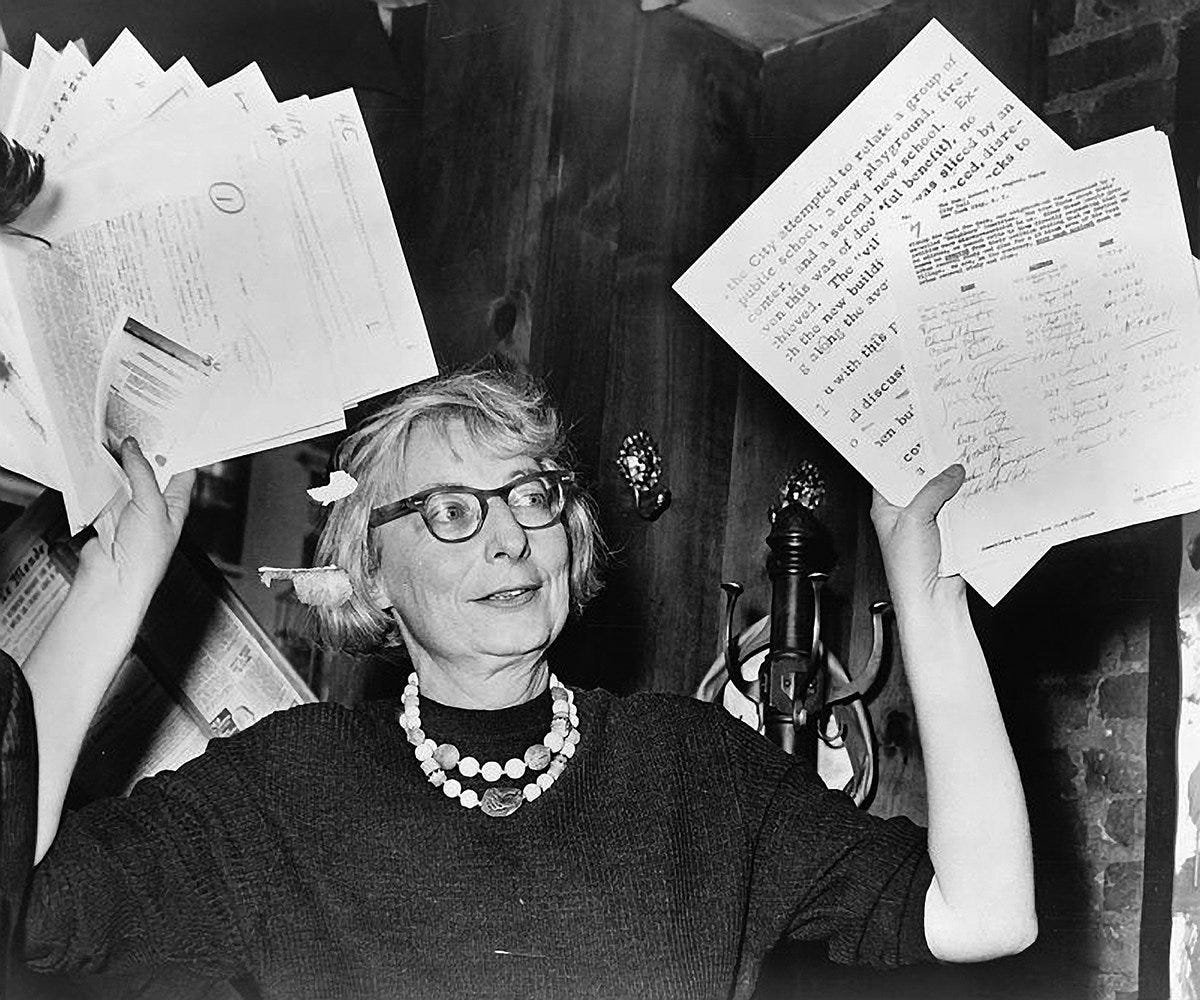

Washington Square Park, 1961. It was here that Jane Jacobs came to brawl with Robert Moses, the larger-than-life planner of housing and transportation for a rapidly modernizing postwar New York City, and effectively ended the era of authoritarian planning.

Their specific conflict was over two of Moses’s many master plans: The first proposed to raze sections of Jacobs’s chaotic, vibrant, and old Greenwich Village to construct Corbusian “towers in the park,” a Bauhaus-inspired modernist style in vogue with the planners of the time. The second plan promised construction of the Lower Manhattan Expressway (LOMEX), intended to connect the West Side of Manhattan to Brooklyn, also by taking out entire blocks of historic Village fabric.

Washington Square Village was ultimately built under the rationale of “slum clearance” and displaced thousands of small businesses. But for Moses, the victory would prove pyrrhic. Thanks to Jacobs’s relentless pen as well as her grassroots organizing, she ultimately stopped the freeway and saved the park. The scale of this fight established long-overdue boundaries for Moses’s unprecedented, ever-expanding powers. As a result, she forced a major turning point in the fields of urbanism and urban planning.

That fight served as an inflection point because Moses’s power grew to where he was no longer accountable to anyone—a critical characteristic of the leviathan-like scale he, and only he, operated at. The planning movement that he led had turned into the most pervasive and damaging tentacle of the early twentieth century’s Progressive Movement was effectively ended by Jacobs’s work. What came next is of mixed consequence.