EQUITY | Engineering Inequity

Current regulatory practices fail to shape public spaces, especially for the most vulnerable.

Written By Anthony M. Sease

This piece was originally printed in Issue 1 of Southern Urbanism Quarterly.

Power shapes cities. Financial power, religious power, the power of ideas—power has shaped human settlements for centuries. Among the most powerful forces shaping the built environment today, especially across growing regions of the American South, are deeply entrenched engineering standards and practices regulating street design. How can such institutionalized practices be restructured to feed the common good rather than perpetuate the spatial injustices of twentieth-century suburbia?

Central tenets of dominant engineering standards and practices were spawned in another era, based on vehicular technology and performance from the 1950s.(1) As Sara Bronin notes in a recent law review article, the authoring of such standards is generated by professional organizations through “years-long, closed discussions among members” who are “mostly technical experts who prioritize, and are trained to achieve, the smooth operation of traffic.”(2) As such, “most aspects of street design are established by or heavily influenced by nongovernmental bodies that are not directly accountable to the public,” a representation flaw.(3) More significantly, though, deep injustices unfold through standards that “prioritize cars at the expense of non-driver safety, and erode quality of place,”(4) creating a public realm which disproportionately fails to “protect individual liberty, including freedom from harm”(5) for those moving about their lives via means other than encased in an automobile.

Like many suburban regions of the South, these are places of immense spatial inequities.

Compared to zoning laws, where changes seem to be unfolding daily at state and local levels to mitigate the nefarious, exclusionary impacts of longstanding practices—ones highlighted perhaps none more impactfully than in Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law(6)—no such nimbleness has appeared in the engineering world. Despite the hope of alternative framings and street design priorities proposed by the National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO),(7) standards grounded in the AASHTO “Green Book”(8)—the omnipresent volume on geometric roadway design standards created by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials—remain far too embedded in the engineering regulatory landscape today. Durham is one such place, unnecessarily so and quite at odds with the prevailing local political ethos of equity and diversity.

In North Carolina’s Piedmont region, power quite literally shaped many towns and mill villages through a tethering to hydroelectric stations birthed by the business acumen of James B. Duke, one of his many legacies in the region. Railroads, too, shaped Piedmont settlements via capital deployed to bring 1800s agricultural products to broader markets. Rail lines often followed ridge lines, an effort to avoid lowlands and minimize river crossings. An infrastructural pragmatism prevailed, one that helped form North Carolina’s urban crescent where much of the state’s population lives still today in that long arc from Raleigh and Durham west toward Greensboro, then southwestward to Charlotte. Durham’s founding spawned directly from that rail, established by the four acres Dr. Bartlett Durham donated to the North Carolina Railroad to serve as a needed water refilling station for steam engines midway between the settled towns of Raleigh and Hillsborough. Spur lines followed, bringing tobacco to the marketplace. Cranky streets and brick warehouses quickly appeared, helping to supply the world-famous Bull Durham tobacco packaged in locally woven cotton pouches to places near and far.

These urban districts, with their spatial complexity and compactness crafted through pragmatism, artisanal care, and patriarchal industries of old, now fuel Durham’s innovation economy. Large brick factory buildings have been repurposed and reinhabited by wet labs and tech companies, architecture and law firms, urban residences and higher education, and iconic brands like Burt’s Bees.

The expanding suburbs of Durham, however, are a different story, spatially and otherwise. In their disaggregated, curvilinear monocultures, civic resilience fades. Tight streets and well-connected blocks of the city yield to auto-dependent landscapes of separation, sections of town where mobility on foot consists largely of three groups: runners with sufficient means for time solely dedicated to recreation; dog walkers, well trained by their canines; and those too young or too poor or too old or too limited in circumstances to have access to a car. It’s this latter group for whom mobility with dignity in the richly provisioned but decompressed landscapes of suburbia is hardly possible. Like many suburban regions of the South, these are places of immense spatial inequities. And among the chief determinants of these rampant spatial injustices are today’s dominant engineering applications, purposefully exclusionary relics of another era portrayed as both technically rational and irrefutable.

For all the recent attention to zoning reforms, housing shortages, and climate change, the most embedded regulatory power in the shaping of the public realm remains engineering myopia writ large. Myopia here is the appropriate term, as the entrenched engineering powers essentially operate with the narrowest of interpretations of health, safety, and welfare. It is this triumvirate—health, safety, and welfare—that serves as the statutory basis of the profession and permeates its educational and licensing norms. In this narrowness, in the absence of diverse ways of thinking and working, spatial injustices spread unfettered.

The battles between engineering and planning inevitably play out with deference to the group presumed to be more technically grounded.

Importantly and promisingly, where creative, innovative engineers have staked out alternative approaches embracing complexity rather than uniformity, the tide has started to turn. Chief among such examples is NACTO, mentioned earlier. Notably, across a scattering of towns and cities, and for many years, engineering regulators have applied pragmatic, contextualized interpretations authorizing slower speed, more pedestrian friendly and more equitable street environments. Such designs include narrower widths and things like offset or angular intersections, tighter centerline and curb radii, and yield streets, all essential elements in increasing friction, slowing speeds, and enhancing safety for non-vehicular users of the public realm. These intentional design techniques applied at the outset—still fully accommodating emergency access and public services—help avoid things like the retrofitting of speed bumps onto over-designed suburban streets.

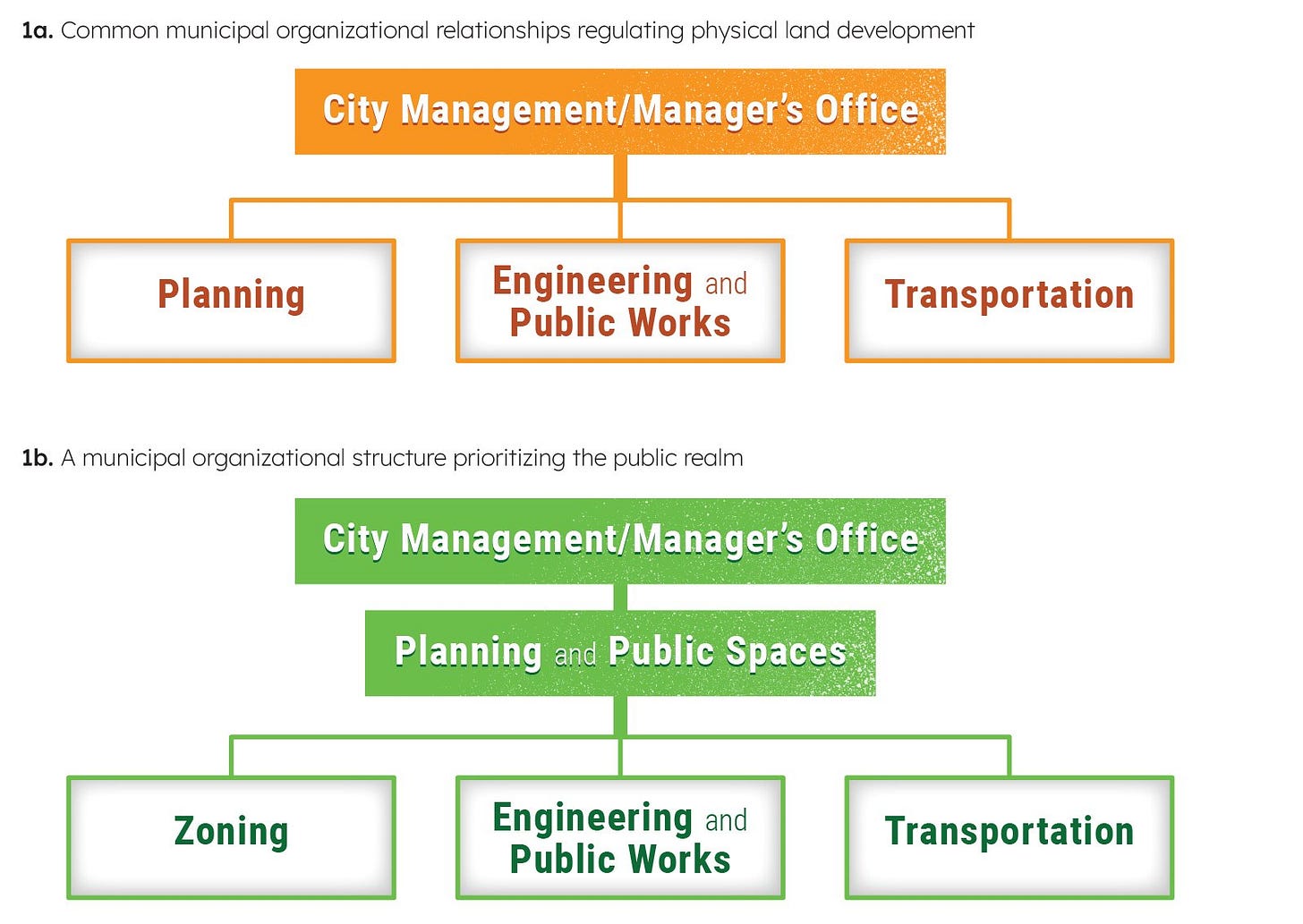

So, what can be done? NACTO holds promise, especially in locales with willing leadership. But given the slow uptake of such professionally endorsed alternatives, other disruptions are needed. One possibility would be to flip the power structure of municipal engineering and create a Department of Public Spaces. Have it report to city leaders or housed in the city manager’s office, with directive over rather than subservience to the engineering and public works authorities. Such an approach is illustrated in the figure below. Bronin identifies the lack of public accountability in how conventional engineering standards are crafted, adopted, and interpreted. That structure must be changed. But as most cities are structured, with planning departments organizationally in parallel to transportation or public works, the battles between engineering and planning inevitably play out with deference to the group presumed to be more technically grounded, the “hard” science winning out over the “softer” science or the more social orientation of urban planning interests. Durham, with its political ethos grounded in equity and diversity, is ripe for such a municipal reshuffling.

The mere mention of Durham’s public works requirements elicits cringes among developers and consultants, likely for perceived inflexibility more so than any substantive outcomes. But that reputation for inflexibility highlights its power, ill-aimed or not. That Durham’s public works requirements exceed a reasonable safety rationale for slow speed vehicular environments is demonstrated by the dual paths of two current residential development projects.

In one case, a higher-end development of million-dollar homes, the geometric and dimensional requirements being applied in the regulatory review are based on two text commitments attached as part of a zoning approval categorizing all internal vehicular access as “private driveways.” For this project of forty-plus residences, provisions for fire and solid waste vehicles are also explicitly required. In the second case, a nonprofit developer is seeking site plan approval for a project with a similar number and mix of smaller housing units under a similar but older zoning document. That zoning request did not include the explicit caveat for access via “driveways,” so this second project is being held to more rigid street design standards despite comparable numbers of the same residential types. To be clear, construction materials or maintenance costs are not the issue; rather, the concern is simply the dimensional and geometric requirements for a small neighborhood of single-family homes. Such dimensional criteria of the public realm are essential in designing for the safety of all users, versus privileging those in cars.

The discussion is about breaking through the shackles of engineering conservatism that relegates pedestrians to second-class citizens and creates environments where to move about one’s daily activities freely requires access and means to a car.

In the instance of private ownership, fire and solid waste access and utility requirements must still be accommodated. Understandably so. Yet, for a similar number of housing units, the nonprofit affordable housing developer, having missed the nuance of asking for a special provision at the time of rezoning via the very same mechanism, is required not only to meet fire and solid waste access, but to meet the codification of suburban standards as represented in the “Reference Guide for Development” created by and administered by the Public Works Department.

This “Guide”—a misnomer given its strict applicability—is not applied to street design for the private, higher-end development. Perhaps Public Works would claim those are not streets, but that is not the issue; from an access perspective, from an engineering safety perspective, the spaces are serving the same purposes, accommodating the same types of daily trips and emergency access to the same types and similar numbers of residences. Thus, Public Works’s implied claims of safety as paramount are undermined with different requirements being applied to the same uses with similar densities. The only difference in regulating spatial dimensions is a zoning entitlement, not fundamental means of access and safety. Again, this isn’t about who pays the cost of maintenance, something imperceptible to the everyday users of the environment. If anything, city concerns about cost would lead to municipal preference for the less expensive infrastructure, for less pavement and less surface runoff. Instead, though, they adhere to norms dictated by their own standards, standards adopted without the accountability of a public process of engagement or review, just as Bronin describes.(9)

The equity implications in comparing the two cases are tremendous, a clear instance of differing interpretations of health, safety, and welfare being applied to one project versus another set of design parameters applied to the affordable housing neighborhood. The safer environment for the pedestrian is the one with slower speeds, with travelways no wider than needed for the purposes being served. In these two examples, the latter condition is offered only to the project with million-dollar homes where costs of maintenance are carried by the private parties. Functionally, though, there is no difference.

The example of the two projects in Durham is just one of many manifestations of the conflicts that arise out of minutiae in entitlements versus pragmatic and broader interpretations of health, safety, and welfare. The discussion is not about high-density urbanism. It’s about breaking through the shackles of engineering conservatism that relegates pedestrians to second-class citizens and creates environments where to move about one’s daily activities freely requires access and means to a car. It’s about structuring and positioning public works departments proportionately relative to other interests and perspectives, to serve the common good rather than dictating by default what group of citizens—by age or economic means or by free choice—can exist in the public realm going about their daily lives with dignity.

Tony Sease is an architect, civil engineer, and urbanist. He is also an Adjunct Assistant Professor at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment and serves on the Durham Planning Commission. Find him at civitech.us.

(1) For a detailed historical overview of engineering standards and the shaping of the city, see Michael Southworth and Eran Ben-Joseph, Streets and the Shaping of Towns and Cities (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2003).

(2) Sara Bronin, “Rules of the Road: The Struggle for Safety & the Unmet Promise of Federalism,” Iowa Law Review, v. 106 (2021): 2174-2175.

(3) Bronin, “Rules of the Road,” 2167.

(4) Bronin, “Rules of the Road,” 2178.

(5) Bronin, “Rules of the Road,” 2158.

(6) Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2017).

(7) Among several NACTO resources, see: National Association of City Transportation Officials, Urban Street Design Guide, (Washington, DC: Island Press, 2013).

(8) American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials, A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets, 7th ed., (Washington, DC: AASHTO, 2018).

(9) Bronin, “Rules of the Road,” 2164-2167.