CITIZEN BUILT | Small-Scale Projects That Inspire

Topher Thomas showcases the power of democratized development.

Written By Gwen McCarter Nagle

This piece was originally printed as the first installment of Citizen Built in Issue 1 of Southern Urbanism Quarterly. The reoccurring series highlights the non-professional citizens who are building their cities.

When Topher Thomas began building an accessory dwelling unit (ADU) in his Durham backyard, he wasn’t exactly planning ahead. It was something he just did. He did it with his own hands, using discarded materials from a nearby dumpster. The fact that he did it at all is astonishing enough. Even more interesting, though, is why he did it.

At first, the motivation behind the ADU was something akin to curiosity. In 2019, Topher had been building furniture out of abandoned materials, and eventually, the question presented itself: “What if I built a whole house out of this stuff—out there in the backyard by the pecan tree?”

His wife was skeptical. Specifically, according to Topher, “My wife said, ‘Hell no.’ But I pestered her about it.”

On the one hand, the project made no sense for the couple and their family. He was earning a teacher’s salary. She was taking care of their two young kids. But on the other hand, the idea that Topher might be able to create a livable structure that could then be rented out for extra income—that made perfect sense. And over time, the case for the ADU practically built itself.

Topher surmised that an ADU could bring in a few hundred extra dollars each month. But what drove him to pick up a hammer and start building wasn’t just necessity. He and his wife had also been noticing what was happening outside their home. “Houses from the 1920s were getting torn down for McMansions,” Topher said in an interview with SUQ. As a result, people in and around Downtown Durham were being shut out, made to believe they no longer belonged in their community.

This marginalization bothered Topher and his wife on a deep level. “I care about how people feel,” he explained. And that outlook led to action.

The calling that animates Topher’s work is about making radical change.

Once completed and functional, between December of 2019 and March of 2020, the ADU housed a tenant. It provided the family with $500 more each month than they had been earning before.

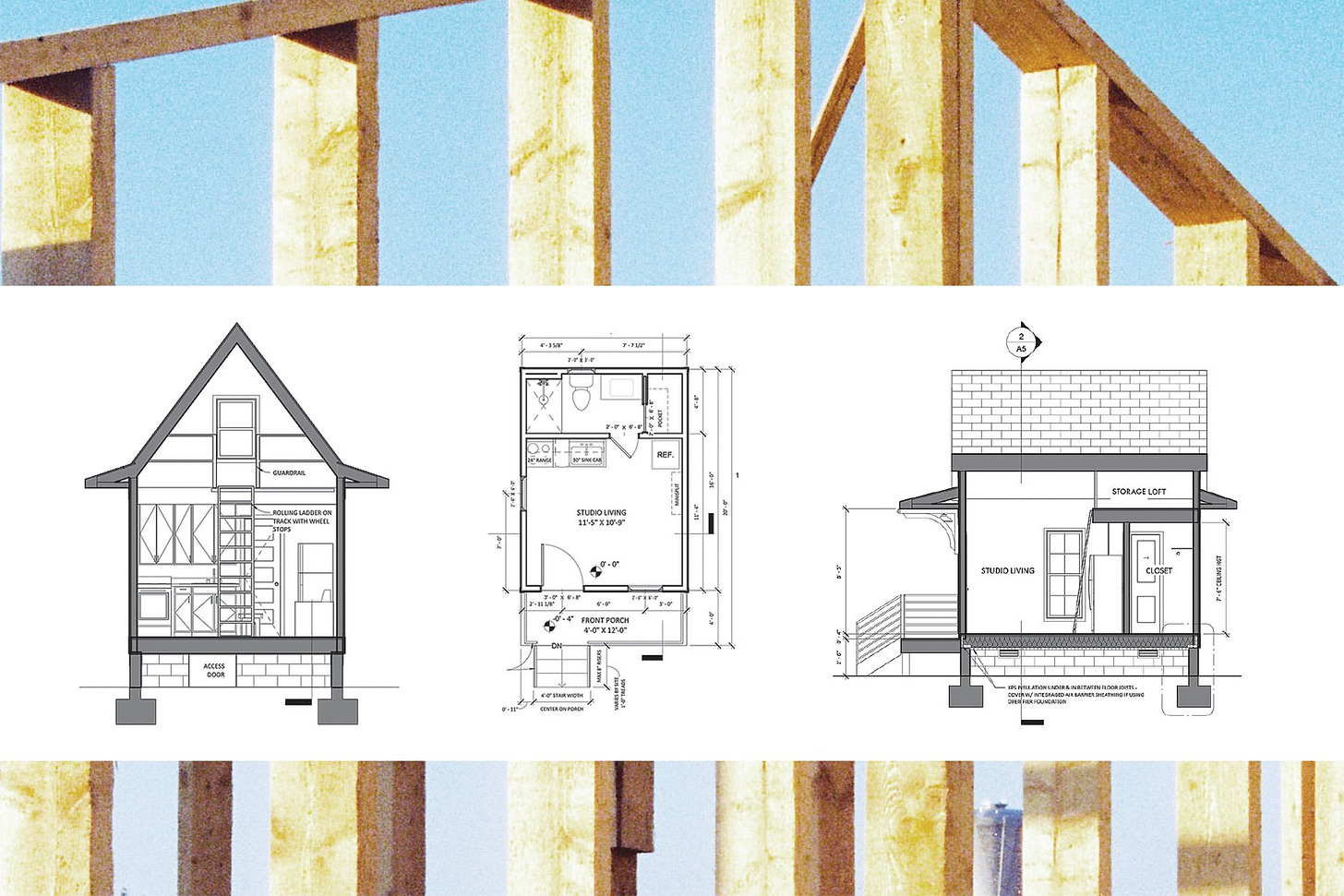

This first iteration of the Thomas family ADU was a structure of slightly more than 12 x 12 feet, which exceeded a critical North Carolina building code threshold. According to the text: “Accessory buildings with any dimension greater than 12 feet shall meet provision of [the] code.” By that standard, Topher’s ADU should have gone through a permitting process, though city rules and regulations weren’t on his radar at the time. At the same time, a neighbor complained. Topher was forced to take the building down.

Of course, timing really is everything. Just as the City of Durham was declaring the ADU to be illegal, the pandemic was taking hold. And once COVID began to derail normal life, Topher found himself home from teaching. He took the opportunity to research how to build a proper structure. Not merely a box, but a residence—and a properly permitted one at that. He thought about the smallest thing he could build that someone could live in. And by August of 2020, he had created something new. It was still a rectangle, and there were only 120 square feet. But it was nicer. There was a loft.

In the summer of 2020, Topher wasn’t just busy rebuilding the added source of income for his family. He was also witnessing the housing market continuing to heat up. What he and his wife had observed in 2019 seemed to be getting worse. More people were having a hard time. And that’s when he began to see the bigger potential of where his focus on small homes could lead.

“I had a strong belief that people really want to help but just don’t know how.”

“People were asking me how to do this,” Topher said. The appeal of his model was becoming clear: Homeowners could have an ADU in their own backyard that could supplement their other earnings, whether they chose to rent it out to strangers or friends. Either way, they would be helping both themselves and others struggling to find a place to live in the area where they wanted or needed to be. It was a win-win. The problem was, most people didn’t know where to start.

Before long, Topher knew he wanted to form a company, and Coram Houses was incorporated in February of 2021. With his new venture, Topher was creating a system for people to duplicate what he did—creating housing without significant building knowledge or access to capital.

“I had a strong belief that people really want to help but just don’t know how,” he said. With Coram, he set out to enhance people’s knowledge of their city as well as their financial literacy. The company helps them get the kind of funding that works for them, and then it builds an ADU with whatever money they secure. Coram started by building four homes, and at the time of writing, it has eight more ADUs in progress.

Looking at why Topher builds, there are layers. Around the edges of his work, those layers look more pragmatic. Yet at the core of what he does, something different emerges: a calling. What he does involves money, and it involves building wealth. But it’s about more than that. The Coram Houses website describes his business as “a community organization committed to breaking cycles of racial and economic injustice through creative and affordable housing.” Seen from that angle, it’s fair to say the calling that animates Topher’s work is about making radical change. He builds to make a difference in his life, in the lives of others, and in the lives of people he’ll probably never even meet. He builds because he wants to help his neighbors, his community, his city, his world.

If you ask Topher what’s next, he’ll tell you about his plan. By 2024, he means to secure about $2 million to build out Coram’s teaching efforts and expand the company’s geographic reach. But he’ll also tell you about his vision. The future Topher wants to see—the one he wants to help build—involves ADUs in every backyard. That future won’t just push back against an untenable housing market and an environment where people are fighting to belong. It will “maximize hope, mutuality, solidarity, and community.” The very existence of the ADUs will promote stability and possibility. But they will also take on a life that’s bigger than the sum of their materials alone. Some of these homes will be integrated into existing neighborhoods. Others will form micro-neighborhoods of their own, taking shape as tiny communities on lots that were previously deemed unbuildable. Such locations will require zoning variances, and Topher isn’t afraid of working to get them. Hearing his story, it seems he isn’t afraid of much. And that’s where Topher’s work is truly inspiring. He was called to build and to help, and in doing so, he’s spread- ing that seed of change as far as he can reach.

Gwen McCarter Nagle is Editor In Chief of Southern Urbanism Quarterly.