Building Optimism, An Excerpt

Why our world looks the way it does, and how to make it better. In book form!

Southern Urbanism has partnered with Building Optimism and Building Culture to bring you the best stories from the people who build our cities. In his most recent essay, Coby Lefkowitz shares an excerpt from his new book.

This is an excerpt from the first chapter of my book, Building Optimism. Building Optimism is the culmination of several years of research into the state of the North American built environment. My aim in writing it was to demystify how the process of city building works, and provide an inspirational guide for a better tomorrow.

Through an exploration of how we arrived at where we are today, a series of concrete reforms, and examples of recently completed projects, I hope Building Optimism can call on the imaginations of builders, architects, developers, planners, city officials, and everyday people interested in making their neighborhoods just a little bit better. That not only is such a pursuit possible, but that it is exactly what our world needs today. Our best efforts are not behind us. All it takes is a little bit of Optimism to get started, and an honest confrontation of the status quo to drive towards the outcomes so many are clamoring for.

My many thanks to all who have supported this adventure so far, and my warm welcomes to those who are joining today. With deep appreciation and affection, Coby.

Chapter 1: On Building Optimism: A Brief History of How We Got Here

Most new places in North America aren’t very good. From sprawling tracts of homogenous homes and strip malls full of chain stores, to anonymous five-over-one apartment buildings and offices located in the most grotesque usage of the word “park” in the English language. For nearly a century, we’ve extracted beauty and joy from our towns and cities, only to replace them with boxes of varying sizes along ever-widening roads, damning the environment, our cities, and ourselves in the process.

When looking at the landscape of recent development, it’s easy to lose faith in our ability to do good things. It feels as though we’ve forgotten how to do it, or moved past a time where creating such places was desirable. As profit imperatives weigh ever more heavily on the development process from both large institutional groups and smaller speculators—who care little for lasting quality—value engineering and spreadsheet architecture have proliferated, pushing the dream of a better world ever further from our grasp.

Somewhere along the way, we’ve accepted this as the status quo, acquiescing to a world with many serious challenges, deficiencies, and high levels of undesirability. In order to cope with it, it seems, many of us have simply become numb to the world around us. Instead of enjoying a walkable, dynamic, salubrious, sustainable, and lovable community as the place where we live full time, those fortunate enough to travel internationally have settled for a few days in some city halfway across the world, at considerable expense, to satisfy these conditions. Those less fortunate are left with little to do but accept the fate cast unto them, sometimes questioning, but rarely being provided for.

We’ve come up with all manner of excuses for why we live this way, from the cost it takes to develop good places and our inability to create them, to a favored scapegoat or conspiracy that places blame on some faceless evil actor as a further coping mechanism. These excuses do little more than shirk the responsibility and render many to believe ours is a world incapable of reform.

I know what you might be thinking. North Americans want a big yard, picket fence, and highways to ferry them everywhere seamlessly. This is just how we do things here. We don’t build walkable, beautiful communities here. And even if we did want to create more of these places, nothing will ever change, because that’s not how our societies are structured. This is the world we’ve been given, might as well accept it.

Not the most positive start for a book about optimism, admittedly. But hear me out! If we’re to embark on a mission to create a better world for tomorrow, we have to know what we’re up against, and accept some foundational truths. Except to illustrate what a more optimistic, common sense foundation might look like, negativity will be minimized in these pages. Promise. It’d be far too easy to criticize the state of contemporary development patterns, or lament the decisions that have put us in this position, without offering an antidote to them. That’s just complaining.

Moreover, the prevailing cynicism of how many view our world is not acceptable. Not when the built environment has such a profound impact on us. Not when much of this cynicism is unfounded. And certainly not when we’re in a position to do something about it.

We spend the vast majority of our lives in places shaped by other people—what urbanists and architects call the built environment, a term I’ll be using so much you’ll either find a familiar comfort in it or never want to come across again. Be forewarned. This goes well beyond skyscrapers and highways; except for those fleeting moments in untouched wilderness, virtually all of the interactions we have with the world are in the built environment.

As humans, we have a funny habit of not being able to leave any patch of Earth we come across untouched. These interventions might be as subtle as a path stamped down in an overgrown forest, or stone walls meant to delineate boundaries—so masterfully done that they feel as though nature put them there herself. Even fields that seem as pure as the highest mountain peaks are often the result of land intentionally cleared of trees, where nothing has grown in their stead.

There are other places we might not traditionally associate with “the built environment” that have been nursed by people and whose natural beauty has been augmented as a result of it, such as gardens, hiking trails, or parks. So even when one thinks they’re outside the grasp of human reach, chances are they’re still well within it.

Why does this matter? It matters because where we spend our time significantly impacts our mental and physical health, and cognitive function. Economies hinge on good or bad development patterns. Communities rise or disintegrate based on the spaces they’re provided. Natural and built environments are either destroyed or rendered more prosperous through the result of our actions. While I could draw dichotomies ad infinitum, simply put, every aspect of one’s life is influenced by the quality of the places they’re surrounded by. If we’re surrounded almost exclusively by settings of our own making, few things could be more important than making these places right.

The cynic might despair reading this information, as it seems that for much of the last century we’ve only been capable of creating places that are extractive, utilitarian, and destructive. Why create anything, they might ask, if it’s just going to be bad? What’s the use in surrounding our bad places with even more bad places? We’d be better off doing nothing.

This way of thinking might make sense at surface level, but when we dig a bit deeper it doesn’t pass muster. There are countless examples of extraordinary places created by people around the world. Rome famously wasn’t built in a day, but took centuries of incremental growth to form itself into the city so many of us admire today. The same is true for thousands of other villages, towns, and cities we dream of visiting or living in. If these settings were created once, there’s no reason why we can’t create them again. It’s not as though some immutable laws of the universe prohibit us from doing this. Every place you interact with in the built environment is the result of a series of decisions—the dreamy, the dreadful, and everything in between. A line can be drawn from everything you see in the built world to a single decision made in a planning meeting, a back office, a section of zoning / building code, a construction document, or the sporadic choices individual people make outside the bounds of formal municipal approvals.

It’s true that we’ve made many bad decisions in the recent past. But that doesn’t mean we can’t reverse our course and draw new lines to chart a better future. Our inaction is the only limiting force preventing us from redirection. It may be difficult, but history shows us a better way is possible.

⁕ ⁕ ⁕

The only reason we have a framework for knowing which places are lovely, and which places are less so, is because there are both exceptional and poor examples all around us. If we didn’t have good references, we’d have no basis for understanding the bad, and no ability to compare the two. So, at the very least, we know that we’ve created some lovely places in the past. Point to the good guys! While this may seem trivial, it’s not only worth noting, but deserves celebration. So strong is our fatalism that we forget how much good there is around us, especially in our own backyards.

While even the most ardent pessimist would have to concede that the world has many wonderful places that are worthy of our dreams and praise (who can dispute the magnificence of Florence, Amsterdam, Havana, or Marrakech?), they might counter that in North America, we just don’t have that heritage. This isn’t true.

We have in our close reach an abundance of extraordinary cities and towns. From Old Quebec, to pockets of Philadelphia, Manhattan, Brooklyn, Charleston, D.C., New Orleans, Montreal, Chicago, and Santa Barbara, hundreds of such locations exist. It must be true, then, that at one point we possessed the skills for creating great cities and towns. We are no cultural exception to the creation of great built environments.

This doesn’t mean that everything we built in the past was inherently good. We may well suffer from a survivorship bias that overrates prior ages of building because only the best homes, warehouses, offices, and monuments made it through to the present day. Many structures of the past, if not most, were not of sufficient quality to last. Conditions of the industrialized powerhouses of Great Britain and America in the 19th and early 20th centuries were infamously bad. In the wake of Chicago’s devastating 1871 fire, wooden tenements were hastily erected to house all those affected by the disaster. These slums soon became overcrowded as the city struggled to house its rapidly growing population. From 1870 to 1880, Chicago grew by nearly 70%, from just under 300,000 people to just over 500,000. By 1930, nearly 3 million more people would move to the city in the hopes of securing economic and personal liberation that was largely unattainable on the surrounding farms and in the distant lands they arrived from. If overcrowding was an issue in 1871, it was an epidemic just a few decades later. People crushed together in quantities that would be inconceivable today. Quite a bit tighter than splitting a bed with your brother and sister on a family road trip. Families were much bigger than they are today, and several families might live in the same apartment, with five, six, or seven or more people sharing one small room. Very little light got into these homes as the buildings covered almost 100% of the lot area.¹ Air quality was abhorrent. Homes crowded around factories that belched soot and God-knows-what-else into the precious little circulating air within them. These places couldn’t be described as habitable, not by industrial standards, and certainly not by modern judgements, barely rising to even a utilitarian level.

“Penury and poverty are wedded everywhere to dirt and disease,” wrote Jacob Riis in his pioneering 1890 work, which documented the conditions of slums in New York City in the 1880s.² Continuing, Riis noted, “Neatness, order, cleanliness, were never dreamed of in connection with the tenant-house system . . . while reckless slovenliness, discontent, privation, and ignorance were left to work out their invariable results, until the entire premises reached the level of tenant-house dilapidation, containing, but sheltering not, the miserable hordes that crowded beneath smouldering, water-rotted roofs or burrowed among the rats of clammy cellars.”

Elsewhere in New York, shacks and shanties that bore some resemblance to pre-industrialized logging camps were widespread. Where just a quarter century later these sites were occupied by grand pre-war apartment buildings that have since come to be revered around the globe, in the 1890s they hardly rose to the title of informal settlement.

How did the penury and poverty that Riis observed give way to distinguished structures and enviable addresses? In order to answer this, we must take a quick diversion across the Atlantic. Though this book is (primarily) focused on North America, it’s worth taking a look at London, as many American projects took inspiration from the progress made in the British capital.

The first “Model Dwelling” schemes arose in London in the 1840s, uniting the need for higher-quality housing for the working poor with subjective moral imperatives. These interventions aimed to improve the overall station of life for the most impoverished, not just where they lived.³ Model Dwellings were erected for all different types of people—single men, single women, families, the elderly, and the infirm. Their scope ranged from small dorms consisting of individual rooms with shared common bathrooms and lounging spaces, up to several-room apartments that families could comfortably occupy. Philanthropists and activists who wanted to move beyond simply campaigning for improved living conditions to putting their principles into practice were the progenitors of these schemes. Social reformers, as they became known since their work sought to reform society, refused to accept the intolerable conditions faced by the many vulnerable who were subjected to them.

Octavia Hill was one of the key figures of this movement, and among its most prodigious. At the peak of her work, she cared for the homes and lives of 4,000 East Londoners, relying on strict rules to uphold order.⁴ In working with the Kyrle Society, whose slogan was “Bring Beauty Home”, she focused on delivering high-quality housing with access to open space, fresh air, and constructive entertainment like literature, art, and music.⁵ For Hill, simply providing better living conditions wasn’t enough. She sought to offer an example of what a more honorable, robust, and enlightened life might look like. She believed in the importance of cultivating communities that transcended the utilitarian mode of charity that prevailed at the time, with a maternalism that demanded her residents mold themselves into upstanding members of society.

These themes were consistent with the work of other reformers in the London scene, though redevelopment through slum clearance was often favored to Hill’s insistence of renovation in place. Sir Sydney H. Waterlow founded the Improved Industrial Dwellings Co. in 1863, which aimed to instill pride in the lives of the 30,000 residents who lived in one of his more than 6,000 buildings.⁶ Plans for IIDC’s Langbourne Buildings in Finsbury Square noted that it was “advisable to give to each dwelling an individuality of appearance; and also dissipate the feeling, unfortunately but too general, that the occupants of the ‘model dwellings’ are the recipients of charity”, lamenting that it was “unquestionable that in most of the buildings of this class the long rows of windows have a dreary monotonous effect, and impress on the mind the idea of a workhouse or of a penitentiary.”⁷ Matthew Allen, who authored the Langbourne plan on behalf of Waterlow, continued, “I am not alone in believing that the homes of workmen cannot by any possibility be rendered too attractive, complete, and comfortable; and that while they will often meet with stolid indifference anything of a ‘missionising’ tendency, the working classes gladly welcome and warmly appreciate the efforts made to obviate the evils and improve the condition of their dwellings.”

The Boundary Estate, perhaps the most successful social housing scheme of the time, was a redevelopment of the Old Nichol, one of London’s most infamous slums and inspiration for popular books of the time depicting the squalor of industrial life, like the polemical A Child of the Jago. Unlike other projects that were carried out by social reformers, charitable trusts or religious institutions, the Boundary Estate was spearheaded by a local government agency, the London County Council. It was one of the earliest government-led social housing schemes in the world. Homes for 5,500 were planned. Although officials desired everyone who had lived in the Old Nichol to have a home in the Boundary Estate, many were not rehoused due to the difficulty in tracking down those who had lived there previously. Others who could be found but were not rehoused had secured accommodation somewhere else during construction and didn’t want to go through the trouble of moving again. Unlike many Public Housing projects that have been built since, the Boundary Estate was mixed use, functioning as a proper community, with 18 shops, 77 workshops (to encourage entrepreneurship and more socially acceptable hobbies than gambling, drinking, and general debauchery), and two schools.⁸ Not only did the Boundary Estate dramatically improve the conditions of the old slum notorious for crime and insalubrity— and provide opportunities for jobs and more respectable leisure—it did so in style. Architect Owen Flemming’s plan, with aid from his colleague Rowland Plumbe, saw 1,069 dwellings of extraordinary aesthetic value erected across 23 blocks. The redevelopment was of such high quality that many of the original buildings have been preserved under Grade II listing status, signifying their importance as cultural landmarks.

Fall at the Boundary estate (top). Rochelle School at the Boundary estate (bottom).

Back on this side of the Atlantic, social reformers like Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr of Chicago’s Hull House, and Stanton Coit and Jacob Riis in New York, drew inspiration from the British to cure the destitution faced by residents in America’s worst slums.⁹ The ills of neighborhoods like New York’s Five Points and the Lower East Side (including modern-day Little Italy, NoLiTa, and Chinatown), Chicago’s Near North Side and Old Town, and Philadelphia’s Society Hill and Queen Village were confronted head on. Hannah Fox and Helen Parrish of the Octavia Hill Association of Philadelphia (which, as you may have guessed, took direct inspiration from Octavia Hill’s work in London), were noteworthy for the incrementalism of their transformations.¹⁰ Workman Place along South Front Street in Queen Village endures as a proud, and attractive reminder of the possibility of positive reform. The homes remain among the highest-quality stock in the neighborhood, with ample outdoor space, much greenery, and considered detailing. Few would recognize them as the deeply affordable housing of their day.

At the larger scale of the intervention spectrum was Alfred Tredway White. A 19th-century engineer, White was also a devoted philanthropist, educator, and social reformer. He abhorred the conditions the working classes were forced to live in, believing that the quality of where one lived directly impacted who they became. He wrote: “The badly constructed, unventilated, dark and foul tenement houses of New York, in which our laboring classes are forced to live, are the nurseries of the epidemics which spread with certain destructiveness into the fairest homes; they are the hiding-places of the local banditti . . . in fact they produce these noxious and unhappy elements of society as surely as the harvest follows the sowing, and by these, punish the carelessness of those who own no responsibility as keepers of their brethren.”¹¹

Convinced that salubrious housing was critical to improve the quality of life of the immigrants he taught and interacted with in his native Brooklyn, White traveled to England to learn from figures like Waterlow. The influence this had is easy to see. The IIDC’s emphasis on providing handsome dwellings for the working class is masterfully reflected in White’s Home, Tower, and Riverside Buildings, all designed by William Field & Son. Located in Cobble Hill and Brooklyn Heights, these 6 story blocks featured outdoor staircases (reminiscent of many of Waterlow’s structures), wrought iron balconies, large common courtyards, and richly detailed facades. They were cross ventilated, which was transformative in an era where few buildings inhabited by the working class enjoyed any fresh air. Units were spacious, brightly lit, had running water, and were tailored for the needs of families. White’s buildings never occupied much more than half of the lot, leaving ample space for playgrounds, gardens, and common amenities in the courtyards.

He experimented with other forms of housing as well, believing people at different stations of life required different living accommodations. At Warren Place Mews, 34 small row houses were built for working class families at low incomes. They rented for just $18 a month when they were completed in 1878, the equivalent of around $600 today.¹² Spanning just 11 and a half feet wide, 32 feet deep, and little more than 1,000 square feet in total, the Romanesque Revival style Workingman’s Cottages are modest but proud structures. Red-orange brick adorns the masonry structures, tactically used in select locations to draw one’s eyes upwards to window lines, pilasters, and entrances framing doorways. A lush and expertly manicured garden runs down the narrow lane which separates the two rows of homes. Each cottage has a dedicated yard in the back. Walking through the mews on its slate pathways, it’s easy to see how living in such a dignified, beautiful place would draw the best out of someone. Lush, intimate, and bountifully adorned, these homes would be a feat most luxury developers today would dream of achieving. Indeed, they regularly sell for well over a million dollars, no small feat for such humble dwellings.

In an 1885 publication for the National Conference on Charities and Correction, White detailed how he was able to deliver the cottages for just $1,150 per home ($35,000 in today’s dollars), or rent out units in his apartment buildings (5th floor walk ups with two rooms and scullery), for as low as $1.60 a week.¹³ Diligently accounting for every expense, he economized on space, bought materials in bulk, and most importantly, employed a “philanthropy and five percent” strategy. Five per cent philanthropists offered their investors an annual dividend capped at 5%, putting a ceiling on profit margins, and by extension, rent. This strategy accomplished a few things. First, it allowed White to keep home prices affordable to the lowest earning members of society, the simple laborers, home cleaners, seamstresses, artisans, and boatmen who made up the majority of his tenants, but who couldn’t pay more than $2 per week in rent. This strategy departed considerably from the speculators of the time who would throw homes up as cheaply as they could in order to chase annualized returns upwards of 40%. It mattered little to these investors when their properties inevitably began to deteriorate just a few years later—they were already long gone. Second, it allowed White to dramatically expand his impact. Real estate was and remains a highly capital intensive industry. As funds for public housing were non-existent at the time, capital had to come from somewhere else. Without investors, no low-income housing would be built, and 5% was a reasonable return on investment for those enlightened benefactors.

After returning ~5% in distributions to investors, all excess cash was either reinvested into the property, spent on events (a six-piece brass band performed every two weeks throughout the summer at his properties), or was given back to the tenants themselves. Surveying his corporation’s financial performance for 1885, $1,177 out of $34,500 in gross revenue (3.4%) was paid back to the tenants in the spirit of “practical co-operation”.¹⁴ These distributions were a “visible recompense to those who by promptness, nearness, and good order contribute the most to the success of the enterprise. These dividends form a great incentive to the tenants to cultivate habits of neatness and promptness.” Aligning incentives in such a way is a win-win. The benefits to real estate managers were obvious. And for tenants, if they treated their properties with respect, they would in turn have better living conditions and receive a portion of the returns (nearly comparable to what private investors received).

Reading through White’s essays and papers, it’s easy to understand how he was able to improve the lives of so many: he cared deeply for the cause. This would not have been possible if he wasn’t fastidious in his management, nor worked hard enough to understand all of the intricacies of how buildings are actually created and maintained.

White’s efforts earned praise from all corners, but perhaps his greatest champion was Jacob Riis, who frequently wrote glowingly of these buildings and their positive impact on the many working families they housed.¹⁵ So inspired was Riis by White’s work that he attributed the philanthropist as his inspiration for How The Other Half Lives.

Through a goal of building “the most advanced tenement houses in the world”, White not only improved the lives of his neighbors, but also inspired builders nationwide to construct a higher standard of housing for the poor.¹⁶ Though he only built homes for a few thousand families, White’s influence extended to many millions, both directly via the creation of The New York State Tenement House Act of 1901 (in which he was instrumental in crafting), and indirectly from those who took influence from his projects and speeches. He is but one cog—albeit a very important one—in a virtuous cycle of profound implications for our built environment.

Remarkably, we now vie to live in areas that were once the most odious slums. Countless buildings developed by social housing organizations are now quite fashionable to live in. That’s sustained Optimism in action. Th is history is not meant, however, to imply that the neighborhoods where these activists plied their trade have not known struggle since, nor that development via social reform is an entirely desirable form of building. Th e paternalism (and in some cases materialism) exhibited by these organizations would not only seem antiquated by today’s standards, but ruthlessly controlling. Many social reformers attached strong doses of subjective morality to their projects, whether via religion, temperance, or strict living standards where tenants had to earn the right to access certain privileges.

Warren Place Mews in Cobble Hill, designed by William Field & Son.

However, just because some of the practices the reformers employed may not be directly relevant to us today doesn’t mean we should disregard the lessons their work has for us. Most notably, we suffer from a lack of the sort of comprehensive vision that can both solve the issues of our times, and propel us forward into collective prosperity. Though there have been some worthy interventions in the last several decades, most of all, there’s been indifference. Instead of a nation driven forward by a distinct “American Dream” for a better world (whether that dream was ever real is a different story for another time), we exist rudderless, paralyzed by the challenges we face. Somewhere along the way, we lost our way.

⁕ ⁕ ⁕

In the years between America’s involvement in World War II and now (though some cracks began to show in the 1920s), the standard of our built environment has regressed considerably. This isn’t to say that the aggregate state of society was better before this regression (it wasn’t) or that things are all bad now (they’re not), but that there’s been an undeniable shift in the state of our cities, towns, and communities generally.

I’ve selected pre-World War II as the general time period for this diversion for a few reasons. Though it’s not a perfect marker, rarely is there ever a single moment in a single place that can be pointed to definitively as the start of something, especially something as nebulous as the quality of community. The key qualification for this inflection point, in my mind, is that before World War II there was a general belief that we could build great things—that our cities could be the envy of the world. Even in the depths of the Great Depression, some of the continent’s most famous structures were completed: New York’s Empire State Building (1931), Nevada’s Hoover Dam (1936), San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge (1937), and Vancouver’s Lion’s Gate Bridge (1938). Across every building and infrastructural typology, in the depths of a moment where hope was in short supply, places of exceptional quality were designed to inspire just that. They were created not only to facilitate their utilitarian raisons d’etre, like allowing cars to drive from one place to another where they previously couldn’t, but to elevate people while they did these tasks. Rockefeller Center, effectively an office park, has no business being as elegant as it is. And yet that is precisely the business it’s in, where magnificence functions as its calling card and has made the development one of the world’s most iconic locations. The same goes for the Chrysler Building.

Regrettably, this hope largely gave way to codified individualism, prejudice, and hyper rationality. Gracelessly, we moved from an age of building grand projects meant to evoke pride, wonder and ambition in the general populace, to a tedious planning and regulation of society for which we cared little for the broader consequences of, and understood even less.

Zoning codes were first crafted in the U.S. in the beginning of the 20th century in an attempt to manage the exponential growth of cities due to mass immigration and the maturation of industrialization. “Manage” is the key word. Los Angeles adopted Ordinance 9774 in 1904, codifying one of the country’s first land use restrictions into law, before expanding on it to form the nation’s first formal zoning codes in 1908.¹⁷ At surface level, the ordinance was aimed at establishing residential districts where industrial uses wouldn’t be allowed. Makes sense; living next to the noxious fumes and loud noises that belched out of factories, with who knows whatever else was released, doesn’ seem desirable. Below surface level, however, the regulation was designed to manage a different, more insidious outcome: racial segregation. Ordinance 9774 was a thinly veiled provision to separate Chinese families and the laundry facilities they ran from their White neighbors. This veil was pretty easy to see through as most of the intensive industrial development in Los Angeles at the time was confined to Downtown, San Pedro, and some other outlying neighborhoods, away from the speculative tract housing developments that were in their first stages of an ultimately successful conquest over the region. If the city had really cared about protecting residential areas from deleterious impact, it would have restricted the extraction of oil, which was far more pervasive than other industrial uses, and in some ways more damaging. Yet drilling continued within neighborhoods without municipal intervention. In some cases, it was encouraged as a form of civic boosterism to flout the economic prosperity of the region. Miraculously, this practice remained for more than a century. If one wanted to, a homeowner could still construct an oil well in their residential neighborhood in the city of Los Angeles as recently as 2021. The county was even later to the game, banning the construction of new wells in 2023, with plans to phase out existing drilling over 20 years.¹⁸

Other early codes didn’t attempt to mask their intentions at all. In Baltimore, the City Council adopted block-by-block segregation in 1910 prohibiting Blacks from living next to Whites. Inspiration quickly spread throughout the South. Atlanta copied Baltimore’s provision nearly word for word (a precedent we’ll see with other zoning codes).¹⁹ Richmond enacted racial segregation via zoning in 1911. Louisville, St. Louis, New Orleans and hundreds of other smaller cities and towns adopted similar laws in the following years.

Opposition to these codes was strong, with formal protests and judicial challenges. In the 1917 case of Buchanan v. Warley, the Supreme Court ruled against racial segregation of residential areas, unanimously holding that prohibiting the sale of real property from one party to another based on race was unconstitutional.

But this didn’t stop land use regulations from being wielded towards exclusionary ends. The racial segregationists of the South found common cause with Berkeley’s 1916 zoning code—the first to regulate residential neighborhoods by their intensity of use. Or, said another way, the first to designate that only single family homes could be built on certain plots of land. While this was not explicitly race based zoning, it effectively was, as only wealthier families (who were nearly exclusively White for other historic reasons) could afford single family homes. Supporters of the ordinance bragged that this would keep neighborhoods reliably free of “Asiatics or Negroes”.²⁰ When combined with private mechanisms like restrictive covenants on the sale of private property that forbade the transfer of deeds to predefined groups, a dark era of segregation in North America was codified, propped up by theoretically pragmatic regulations like Ordinance 9774.

As these seeds germinated, one of the most significant precedents for the next century of development patterns was sowed via the Supreme Court case of Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co. in 1926. In response to industry moving south from Cleveland, Euclid, which borders the city to the Northeast, adopted a zoning ordinance to prevent industrial uses within its borders. Ambler Realty wasn’t happy about this, as they bought land within the village with the explicit intent of developing factories. Euclid’s ordinance, they claimed, amounted to an unconstitutional taking and violation of due process. The Supreme Court did not agree. The majority ruled that using zoning (a relatively new concept) to prohibit certain uses was a valid exercise of a municipality’s police power.

Though presumably more innocuous than other laws that preceded it, the precedent of Euclid v Ambler allowed municipalities to arbitrarily regulate their land to a degree of prescriptiveness without any historic equivalent. Up until the decision, nearly every locale in the world had the right to situate different uses next to, on top of, or below each other. A cafe could comfortably (and legally) exist underneath an office, which might itself be underneath a third-floor apartment. Nothing prohibited a school or a grocer from being located next to any of these uses. If people really wanted to get crazy, they could throw all of these things into the same building, or series of buildings neighboring one another, in any combination they liked. After Euclidean zoning, it became possible to segregate all of these uses away from one another, turning the historic city inside out. And segregate we did.

As satisfying as it might be to lay blame at the feet of one decision, the devolvement of our built environment can’t solely be attributed to Euclidean zoning. While it shaped our society in some meaningful(ly bad) ways, its impact has been dramatically augmented by the scaling up of our communities facilitated by cars and highways. A qualifier before we delve into this topic: in some circles, it’s become popular to view cars as inherently bad for our cities, but this isn’t really true. Motor vehicles only go where roads lead them. They can be phenomenally useful tools if managed correctly. if someone can’t walk well, or needs to urgently see a doctor, quick and efficient door-to-door access is important. Being able to get groceries in the middle of a snowstorm in winter, or visit far-flung family members many hundreds of miles away, are extraordinary benefits.

Cities like Amsterdam and Copenhagen have (in many ways) figured out how different forms of transport can peaceably coexist by balancing allocations of road space to ensure one mode doesn’t overpower the others. Driving a car is just one of several options someone has at their disposal for how to get around (it’s usually not the most efficient or affordable way), so cars can still be used where needed without dominating a city. Not so in North America, where we’ve reoriented our entire infrastructure to become “car dependent” where many of us can’t go anywhere without a car. It didn’t start this way, though.

Prior to World War II, American cities looked much the same as their European and Asian counterparts, just with more grids and a few hundred years less of history. Looking at pictures of Cincinnati or Baltimore, one would be excused for confusing them with Manchester or Liverpool. When first introduced, the advent of cars didn’t really change the fabric of cities all that much. This was evident in Manheim, the German gridded city where the gas-powered automobile was invented by Karl Benz (eponymously of Mercedes-Benz fame). Compositionally, these first cars were little different from the carriages which preceded them, where horses were swapped out for engines. Private cars quickly made their way to the United States, with the first vehicles produced before the turn of the century. But they didn’t truly take off until Henry Ford introduced the Model T in 1908. Prices started around $850 ($29,000 in 2024 dollars) before dropping to the equivalent of $4,600 by 1924 thanks to the efficiencies of the assembly line.²¹ Sales skyrocketed. Where prior models only had production runs of a few thousand cars, 15 million Model Ts were sold from 1908 to 1927. In 1906, there were only 100,000 cars on American streets. By 1927, there were more than 20 million.²²

Model Ts, and other cars, needed roads to drive on. Champions of this new technology in federal and local government were only too happy to accommodate this need. Beginning in 1916 with the Federal Aid Road Act, and continuing through the 1920s with the Federal Aid Highway Act of 1921, the foundation for a network of roads crisscrossing the country was laid down. Over the next two decades, spurned on by generous federal funding, roads were paved around the country, including the famous Route 66. Rural communities, previously difficult to traverse, or completely inaccessible, gained new connections. Uneven, dusty (and when it rained, impossibly muddy) streets in cities and towns were paved over. While this made getting around easier for people bicycling and walking, it also made doing so more dangerous. Bumpily moving along a road at the pace of a horse’s trot requires some degree of concentration. But when streets are easier to drive on, people drive faster, and lose their focus. This leads to deaths. In 1913, the first year of recorded data, motor-vehicle deaths occurred at a rate of 4.4 per 100,000 people, or 4,200 total casualties. In 1937, this peaked at a rate of 30.8, nearly 40,000 people in total.²³

Many of these deaths can be attributed to putting too much power in the hands of those ill-equipped to wield it. With no driver’s education, or even established norms of how one should drive, streets were chaotic. Stop signs, lane lines, and driver’s licenses didn’t exist. Practically anyone could try their hand behind the wheel, with little oversight. Cars had no brake lights, so if drivers stopped short (which happens every minute on the roads), there was no way of anticipating it. For some, this wasn’t an issue, as they breezed through all intersections without a moment’s hesitation, seldom slowing down to see if traffic might be coming from the other direction. There was no reason why they should’ve been so confident—there weren’t even traffic signals to let them know they could go through a green light. Left turns were treated like right turns, with offenders earning the name “corner cutters” for making quick movements against the flow of traffic, hitting unsuspecting pedestrians crossing the other side of the street.²⁴ Pileups were common. Drunk driving, pervasive.

Driving got safer after its Great Depression depths. Things we hardly spend a moment thinking about, like seat belts or reliable brakes, were introduced. Roads began to resemble those we drive on today. Just like zoning, public thoroughfares began to be divided strictly by use. Most frequently, they were dedicated exclusively to cars. Trams, pedestrians, and bicyclists had to find other ways around. This had its benefits, however. Kids were barred from literally playing in traffic. Trains became separated by grade so they didn’t have to compete for road space with other modes of transportation, and railroad crossing signals were implemented. Where streets once faintly resembled the imagined glories of toddlers, with trucks, trains, and unsuspecting action figures smashing together (with attendant whooshing and crashing sound effects), they became more rational, and safer. Thankfully, these scenes now rarely make it past playroom reenactments.

Aside from donning new paved surfaces, the streets themselves were little different than in the pre-automobile era. Gradually, that began to change. Detroit completed the first urban highway, Davison Freeway, in 1942.²⁵ Dozens of homes and businesses were demolished (or picked up and moved) to make way for the road. Davison Avenue was transformed from a tree-lined boulevard to an open-air sewer for cars, splitting the Highland Park neighborhood into two. Subsequent expansions (it currently spans 8 lanes wide) have ensured Highland Park hasn’t recovered since.

Compared to what was to come, the engineers responsible for constructing the first highways were little more than raptors testing the fences, perhaps aware of their power, but not empowered to see it to its conclusion. This changed in 1956, where America’s infatuation with cars and roads was blown open. The creation of the Interstate Highway System unleashed a scale of infrastructure development that was historically unprecedented up to that point, paradigmatically shifting development patterns towards private car ownership. Conceived as a project for national defense by President Eisenhower (the full name of the law was the National Interstate and Defense Highways Act), the bill authorized 47,000 miles of highways that were constructed at a cost of more than $500 billion (inflation adjusted). It took 35 years to complete.²⁶ Conquering farm lands, complex natural ecosystems, and dense urban communities with equal parts deftness and indifference (sometimes bordering on hostility), the Act expanded the previous interstate system by more than 20 times its pre-1956 mile count.²⁷

Though this system was, and continues to be, lauded by supporters as essential to the mid century growth that launched America into superpower status, it was also successful in a different, less celebrated way. The interstate highway system and the broader network of 1,000,000 miles of federally supported roads (out of 4.2 million road miles nationally) ushered America into an era of unique individualism and expanded segregation.²⁸

Yes, the development of a national network of roads allowed for increased logistical interconnectivity and economic productivity, which are both good things as far as I’m concerned. But this prosperity wasn’t shared equally. It was a kind of scattered adventure: connectivity for some, and severance for others. What Eisenhower’s highway system most uniformly accomplished was to stretch us out and pull us apart. These were, after all, key components of the program’s stated goals. As much as the Interstate Highway System was an infrastructure initiative, it was equally a de-densification project to diffuse potential targets in the Cold War, where dense cities could be attacked for concentrated destructive impact.

This stretching and pulling had many adverse impacts. Strong communities were destroyed to facilitate the movement of private vehicles to new communities segregated by class, use, and almost always at the beginning, race. More than 13,500 miles tore through cities, displacing hundreds of thousands and damning those who remained to grim conditions. Enabled by the highways, millions across the country moved out of cities. Most of these emigres were middle class white families, earning the movement the name “White Flight”. They drove along elevated highways, never quite interacting with the city they lived closest to, merely using it transactionally as a place to work from 9:00 in the morning to 5:00 in the evening, before driving back home, ignorant of the destruction that enabled them to live in separate communities many miles outside of the city’s limits. Could there be anything more individualistic than this?

Hardly, but such was the zeitgeist. This was the cultural peak of Modernism, a philosophy that viewed itself as fundamentally scientific, espousing hyper rationalism, individualism, and an embrace of technology to further human progress. You may know some of its exports, like the Scandinavian mid-century furniture favored by anointed tastemakers (and maybe by you as well!), to abstract art that no one really understands when looking at on their own, but are convinced it must be good because those same tastemakers told them so. But Modernism was, and is, so much more influential than this.

By the time World War II ended, Modernism was no longer the avant-garde movement it had once been at the beginning of the 20th century, pushing art, design, and thought to places previously inconceivable. It was now mainstream. Modernism was a philosophy that explicitly rejected the past in an embrace of the future, seductive at a time where much of the world was rebuilding after two devastating wars and a crippling depression. The past had wrought such profound destruction and iniquity on a scale so vast, it was enough to think “pre-Modern” humanity was beyond redemption. One could understand the motivation to move beyond all that was associated with those times. For our cities and towns, this worldview demanded that any traditional place, structure, or way of building become verboten, at least to any sufficiently modern, thoughtful person of the day.

Modern urban planning practices and the private automobile were the perfect tools to rebuild this broken world. They embodied a scientific, rational, and hopeful future predicated on technology, which would allow the world to rise triumphantly beyond its darkest moments. Where the human condition was untenable and messy in the pre-Modern period, a cure for its effective management had seemingly been found.

Modernism penetrated all realms of thinking and creation. In architecture and city building, there was perhaps no figure of greater consequence than Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, the Swiss-French architect and theorist better known by the name he selected for himself, Le Corbusier. Modernism’s abstractions were made tangible in the built environment through his plans. In denigrating pre-Modern communities as laid out along the “Pack-Donkey’s way”, Le Corbusier viewed the traditional city as anachronistic, an overcrowded vestige of habitation from the time before reason and industrial capability prevailed. In this way, Corbu set himself directly against one of the most prominent architectural theorists of the prior generation, Camillo Sitte. Sitte lamented the development of industrialized cities for stripping beauty and the arts out of everyday life. He heralded traditional cities for their intimate plazas, perpendicular streets that met to form terminating vistas that provided enclosure where one’s sighteline down the street was drawn towards a building or monument, and irregularly curving lanes, which he considered vital to successful city-building.²⁹ Le Corbusier did not.

Writing in his 1929 manifesto, The City of To-Morrow and Its Planning, Le Corbusier criticized Sitte’s City Planning According to Artistic Principles as “a most wilful piece of work” describing its advocacy for artistic and organic cities as “an appalling paradoxical misconception in an age of motor-cars”.³⁰ He felt that “a modern city lives by the straight line, inevitably for the construction of buildings, sewers and tunnels, highways, pavements. The circulation of traffic demands the straight line; it is the proper thing for the heart of a city.”

These ideas materialized in Ville Contemporaine, a 1922 plan for a hypothetical city of three million people. Le Corbusier took heavy inspiration from machines, famously stating “A house is a machine for living in” and that, “Machines will lead to a new order both of work and of leisure”.³¹ Revering the mechanized processes of mass production for its hyper-efficient creation of goods, Le Corbusier set about designing his city much in the way a refrigerator or a truck might be produced. If these products could be churned out with precision, consistency, and good taste, he observed, why should a city be any different?

With a rigid orthogonality, he envisioned the city as a collection of strictly segregated zones, where long and wide highways dedicated to private automobiles were the principal arteries of moving from one zone to the next. Corbu worshiped the car and oriented his entire plan around it, similar to the way a church unfolds around a nave. As far as the buildings were concerned, there could be no detailing. Citing the architect Adolph Loos’ seminal Ornament and Crime: “The more a people are cultivated, the more decor disappears.”³² As Modernism was the height of humanity’s intellectual journey, its adherents reasoned, they were too sophisticated to be fooled by the simple tricks of cheap ornamentation, favoring the intellectually honest structures whose form followed their functions. Minimalism would rule the day. When combined with machine processes, Ville Contemporaine’s buildings took the form of stark identically reproduced skyscrapers situated in parks, gradually tapering off in height from the central district outwards to a shorter, but still identical, composition. These buildings were to be evenly distributed around the city as pews to witness the car driving down the aisles of the church of Modernity.

By providing everything with a clearly defined space, separating all uses cured the chaotic competition over scarce land that historic cities struggled with. Building things on top of one another, without so much as a few square feet of relief from the screaming salesman or rabid preacher, was barbaric. Looking down from a bird’s eye view onto the city—a view only possible thanks to the technological progress of the airplane—everything would be perceived as perfectly symmetrical, and entirely rational, befitting the triumph of the Modern man.

Ville Contemporaine was a totalitarian masterpiece. There was to be no derivation from the exacting lines. Everything succumbed to the plan—and by extension, the car. People included. This was the only way to overcome the conditions of the past. Humanity had to be put in place, and internalize that fact.

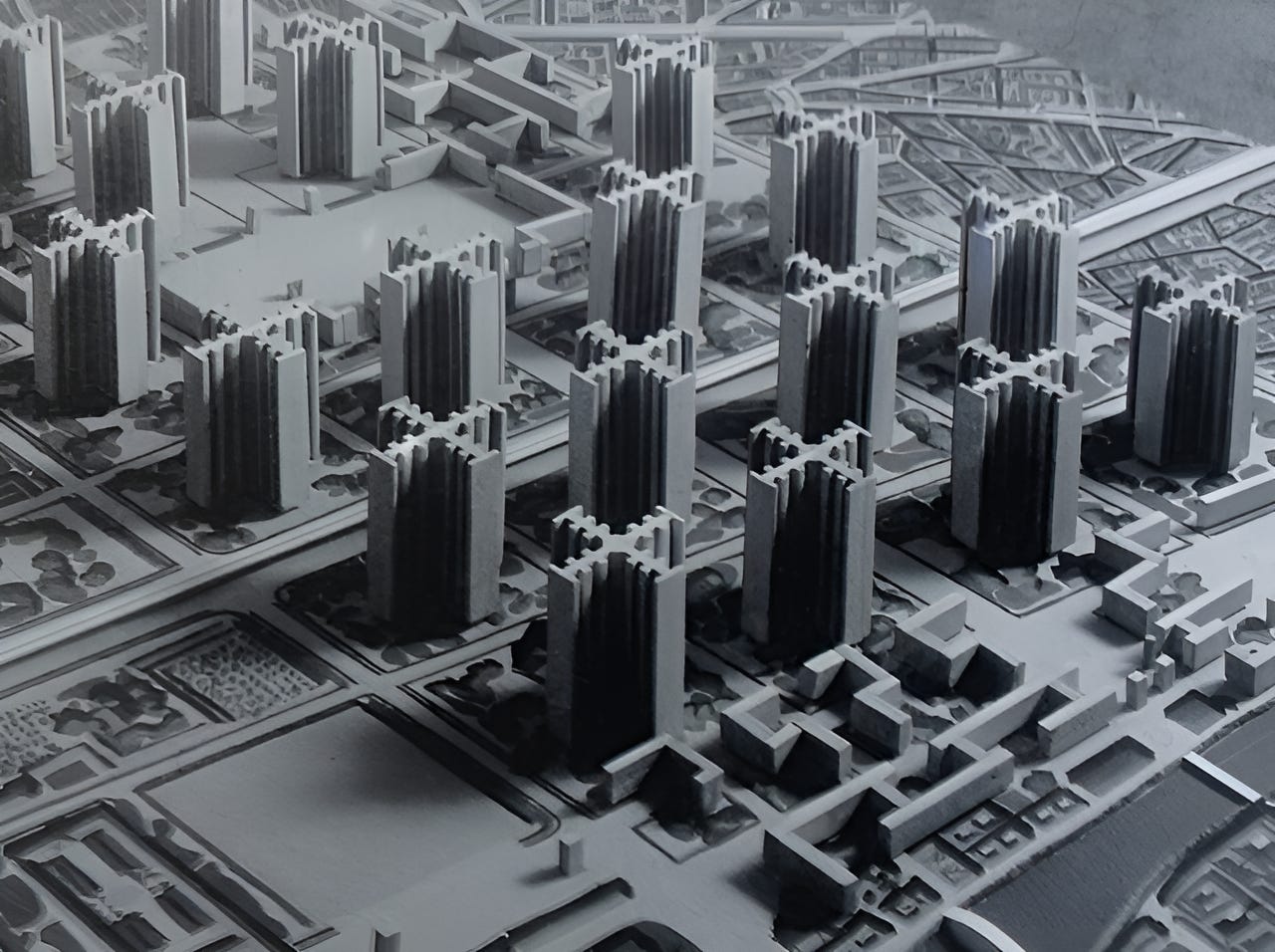

Despite his self-perceived brilliance, Le Corbusier saw little traction at first. He needed something bolder to bring attention to his ideas. What better way to show the superiority of the Modern world over the traditional one than by planning a direct claim over it? Then people would understand. Fed up with the squalor, overcrowding, and perceived anachronistic nature of his adopted city, Paris, Le Corbusier proposed the Plan Voisin. It would cover around one square mile of land in the center of the city, demolishing relics of the past for marvels of the future. Building off of the principles of Ville Contemporaine, Plan Voisin would have provided homes for 78,000 people, in identical four-winged towers. 90% of the land would have been preserved for open space and circulation. Naturally, the proposal was sponsored by a car company (Avions Voisin).

Le Corbusier’s Plan Voisin for Paris.

This was a very different kind of vision for the future than previous optimists had espoused, and it marked a turning point in the history of our built environment. Instead of improving the slums or building new cities with the daily routines and emotions of people in mind, as the social reformers and Sitte valued, Le Corbusier’s Modernist plans rejected human experience for technocratic optimization. He put ideology, technology, and rationalism above humans—though admittedly, we aren’t known to be the most rational beings. Of course, Modernism wasn’t an incontrovertible science (no science is), but rather an aesthetic movement that expressed itself through a very particular vision of the future, prone to the fallibilities and shortsightedness of any ideology that condescends to know all, as philosopher Alain de Botton convincingly argues in his riveting The Architecture of Happiness.³³ Aesthetic or scientific, for the first time in history, cities were no longer planned around the needs of people, but rather, the demands of the car. The consequences would be profound.

Paris was saved from destruction, but other cities were not so lucky. Le Corbusier’s plans were exported around the world. For our purposes, we’ll focus on their landfall on the American side of the Atlantic from the French capital.

American cities had been tinkering with piecemeal elements of Modernist planning for decades, like ordered Euclidean zoning, the mass production of cars, and the creation of highways and modern towers. But it wasn’t until a general philosophy that encompassed all of these elements was put together that their ultimate impact on society would be felt. While there wasn’t ample opportunity to implement this philosophy during the Great Depression or World War II, due to a lack of resources and focus being directed on other fronts, as soon as stability was reached in the postwar period, Modernism presented something of an easy roadmap to guide cities and towns into the future of the 20th century.

This materialized in two distinct ways, which I call the twin swords: one to cut down, the other to cut through. The first sword cleaved highways through dense thickets. Following Le Corbusier’s dictat that normative traffic circulation must take the form of a straight line through the heart of a city, entire neighborhoods were demolished to make way for urban freeways, subsidized generously from the federal government. Gashes often discriminately severed neighborhoods whose land was the cheapest and held little political power such that they couldn’t put up much of a fight. Not only were homes destroyed, but for those that remained, connections to those on the other side became unsupportable. Where two families might have gotten together every Sunday for dinner before the highways were built, afterwards they now had to go around, which could be a significant detour. Without these connections, beloved local businesses closed, community centers emptied, and economic productivity declined meaningfully. Scars from these decisions still exist in many neighborhoods today, segregating and subjugating.

Much like a machete, this first sword hacked vertically through neighborhoods for roads and highways. The second cut horizontally, in service of demolishing blighted slums. Broadly, these were not slums that the 19th-century social reformers would recognize. While it’s true that conditions were quite bad in some of these areas, many were simply gritty working-class neighborhoods, far from the supposed squalor that inflicted them. With caprice and discrimination against minority racial and religious groups, entire neighborhoods were cleared, leveraging federal subsidies from Title I of the 1949 Housing Act, better known as Urban Renewal. Neighborhoods that may have otherwise been perfectly fine if, in the minds of certain planners, not for the color of their residents’ skin or their religious beliefs, were designated as “blighted” and in need of reform.

Wrecking balls crashed through urban fabric, replacing finely networked communities with austere towers that turned their backs on the streets and offered little in the way of geniality. Greenery and open space were abundant, but it was superficial, and not really usable. Patches of grass without programming, seats, or enclosure did not welcome people to spend time in them. They were dead spaces. At night, without lights or protection from security, these became dangerous areas that were best to be avoided. Sadly, those who lived there could not. While good in theory, without effective management or an understanding of the intimacies of what makes for successful design (which none of these developments benefited from), they fell on hard times, and were ultimately neglected by those who erected them Infamous examples include New York’s Public Housing developments (NYCHA projects) and St. Louis’ Pruitt-Igoe complex, which was so poorly executed that it was demolished before it could even turn 20. Pruitt-Igoe remains a vacant, overgrown lot 50 years later, hardly a 10-minute bike ride from the city’s iconic Arch. Other neighborhoods that were cleared for redevelopment as in Norfolk were never built in the first place, displacing former residents and ultimately eviscerating civic life for no reason.

The Wendell O. Pruitt Homes and William Igoe Apartments complex in St Louis. Completed in 1955. Demolished in 1972.

These policies cut beyond our cities, with highways moving outwards from core areas to raze our countryside and form new suburbs. The cause for this may look similar to the challenges we face today; A housing crisis gripped the country following the war. Very few homes were built in the 15 years from the beginning of the Great Depression to V-J Day. This problem was compounded by the fact that GIs returning from Europe and the Pacific were eager to start families but there weren’t enough family appropriate homes. Furthermore, despite strict quotas on who could enter the country (through legislation like the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924), nearly a million immigrants entered the U.S. between 1930 and 1945.³⁴ And this number only includes those who were officially recorded.³⁵ Homes were needed, desperately. The National Housing Agency, a temporary wartime entity, estimated in 1944 that the U.S. would need 12,600,000 new dwelling units during the first decade after the war to meet demand.³⁶

The federal government recognized the dramatic need and got to work. Prohibitive mortgage terms, like high down payments and one year interest payback periods, were revised to allow prospective home buyers to put as little as 5% of the purchase price down, and spread interest payments over 30 years. Lenders might not have done this on their own, given how risky debt could be, so the loans became federally insured, meaning the government would protect against losses from borrowers who didn’t pay back their loans. This gave banks far more confidence in extending mortgages which by extension, enabled developers to secure financing to build the housing the country desperately needed.

Inspiration for these new suburbs was provided, if indirectly, by Le Corbusier. Though they didn’t look like Ville Contemporaine at first glance, compositionally, they were nearly identical. Accessed via straight, orthogonal road systems, these new suburbs were hyper rational. Everything had its place, and nothing could be outside of its own place. Houses here. Strip malls there. Apartments nowhere (less Corbuserian, admittedly). Under the guise of individualism, and abiding to a structure that would make Corbu proud, the unadorned homes were homogeneously mass produced like washing machines or sheet metal, sat in the middle of their own parks surrounded by ample green space, and were subservient to fleets of equally mass produced cars.

With funding at the ready, and a plan cemented for idealized communities, all that was needed was a system that could adequately scale upwards to satisfy the demand. Building 12 million homes requires some level of coordination, after all. Re-enter zoning.

Euclidean zoning is similar to a coloring book. The lines are already there, you just need to fill them in. I should mention it’s not a very good coloring book, as most of the areas are all the same color, which makes for a rather drab artistic exercise and commensurately insipid communities, but I digress. In the post-war period, a page in the Euclidean book would mostly be the color of single family homes (let’s say green), with some pockets of red and blue for retail and office strips. Though boring, this coloring book was very useful for communities who wanted to plan for a future of growth but didn’t have the internal capabilities to do so.

There are nearly 20,000 incorporated places in the United States. For clarity, an incorporated place is defined by the census as “any governmental unit incorporated under state law as a city, town, borough, or village legally prescribed limits, powers, and functions”.³⁷ The vast majority of these units are home to fewer than 10,000 people, making it infeasible for each one to support a planning department. There are only so many planners to go around, and that’s before the churn which sees many trained experts leave the profession in search of more inspired or lucrative disciplines. After the war, most towns didn’t (and still don’t) have the time nor the resources to develop their own plans and codes. It was simply easier to copy what neighboring towns did. And so, standard codes were transcribed from one municipality to the next, straight across the country. No town wanted to be left behind the march of Modernity. For unincorporated areas that had no pretensions about progress, they needed mechanisms to manage the rapid growth which was consuming farmland, and similarly adopted the codes of incorporated areas. This is the genesis of why everywhere in the U.S. now looks the same. Whether you’re in Boise, Tampa, Omaha, or anywhere in between, the coloring book (and the people who color in those lines) is very similar, if not the same. More on this later in Chapter 5.

These new suburban homes weren’t built for all who needed them. Programs were selectively subsidized for populations that public officials deemed worthy. The Underwriting Manual of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), the framework which laid out who would be insured by federally backed loans and who would not, explicitly excluded certain groups. As Richard Rothstein detailed in his influential, Color of Law, the FHA and the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) created maps that designated a gradient of “safe” to “hazardous” neighborhoods where mortgages could be insured.³⁸ If a neighborhood was deemed safe, a mortgage could be issued with minimal concern. But if a neighborhood were labeled hazardous, no loans were to be issued. No loan, no home. No ability to build equity and wealth. This process became known as redlining, because “hazardous” neighborhoods were colored red on the maps, and all who lived in them were deemed too risky to extend a mortgage to.

With the Federal Government’s commitment to building a network of highways crisscrossing the country (de-densifying cities in the process) and the backstopping of loans to support mass construction to solve the housing crisis, funds were near limitless for those who were able to build at scale according to FHA standards. Levittown, Long Island, is the early case study for this pattern of growth. Originally planned for 2,000 homes, so abundant were the funds, so generous were the subsidies, and so strong was the demand, that by 1951 the Levitt family had constructed more than 17,000. Home models varied slightly in later phases, but at the outset they were functionally identical in order to economize costs through efficient production of component materials to deliver as much housing as possible. Through a mass production process not unlike Ford’s assembly line, 26 specialized teams of contractors could build one of Levitt’s 750 square foot cottages in under a day, with each of the 26 steps of the process optimized for maximum efficiency. To further reduce costs, workers were not paid by the hour, but by the number of homes they completed, incentivizing speed. Attics that had room for two extra bedrooms were left unfinished. For those who were allowed to buy a home in Levittown, the deal was almost too good to be believed by today’s standards. GIs returning from war could buy a home for just $7,000, with no money down, and $65 monthly payments.⁴⁰ Purchasers of the homes signed clauses which forbade “the premises to be used or occupied by any other persons than members of the Caucasian race”.⁴¹

Aerial of one of the early phases of Levittown, Long Island.

Suburban Modernism guided American development patterns as a philosophy throughout the mid-century period. So powerful was this vision, and so strong the belief in it, that hundreds of billions of public dollars were leveraged in service of it. Some still believe in the promises of this post-war paradigm today, which have become embodied in the idealized American dream of a generously sized single family home, several car garage, and large lawn separated from all other uses by long and straight roadways. This, many reason, is what rational individualism looks like, the highest state any sufficiently modern person can aspire to be. That it’s effectively a socialized housing and highway program seems to matter little, because people believe so strongly in the original promises of the program and the orthodoxy of individualism.

But gradually the direct connection to this philosophy receded. Divorced from the earliest theorists who were deeply concerned about solving the most pressing challenges of their day, we’ve been left with the vestiges of realized plans that never quite succeeded in translating the enlightened values of Modern theory into place. The result has been an overwhelmingly disorienting, segregated, inefficient, and unsustainable built environment. One that, while temporarily addressing a housing shortage, sowed the seeds for a future one. It is my belief, as we’ll explore in the next chapter, that the negative outcomes this way of building have delivered far outweigh the positives.

It’s been some time since the results of this philosophy were rejected, but there hasn’t quite been another worldview to replace it. We’re simply copying and pasting simulacra of the earliest post-war suburban developments (and institutional urban derivatives like blocky apartment buildings) without thinking about why we’re doing it. Though the earliest subdivisions are no better than the new ones today (they’re probably, on balance, worse), there was an excitement around their creation because they represented a belief in the possibility of a better world that was fresh, innovative, and upwardly mobile. Difficult though it may be to see today, these subdivisions were, in many essential ways, remarkable improvements over the conditions of the past. We haven’t, however, continued the upwards trajectory of our built environment in recent decades. We are copying and pasting the results of policies that are no longer relevant, without questioning the outcomes. Few viable alternatives to bring us into a new era have materialized.

I don’t mean to be dismissive of the work attempted to rectify mid-century development patterns or their vestiges. Groups like the Postmodernists tried to offer another path. Few ideologies, however, can achieve sustained success if they orient themselves around the opposition to something else. Once their opponent vanishes, so too, will they. PoMo rejected the severity, austerity, and rigid formality of Modernism, but did so in such a playful way that arguably it didn’t take itself seriously enough. So how could the rest of the country adopt such a philosophy? While this is a gross underaccounting of the labors of this period, it’s not unfair to say—and indeed it has proven true— that this philosophy was not sufficient to chart a sustained course of progress in the built environment.

After decades lacking a general direction following the dissolution of Modernism, we’ve become untethered from place and untethered from meaning of place as no substantive worldview has taken its position. Modernism, for all its flaws, at least offered some structure for building. We’ve become numb to a world where there is no operating guide for moving forward. The scale of our planning and infrastructure apparatus is so vast and incomprehensible, and our needs so extraordinary, that it seems like we can’t do anything. So instead of believing in something, we find ourselves agnostic towards just about anything. Instead of working tirelessly to solve our problems as earlier reformers did, or dreaming of a better world as the Modernists did, we’ve become prisoners to the codes that have damned us. It is a national Stockholm syndrome. We’ve fallen for our oppressors because we don’t know where else to turn. We feel as though we no longer have any agency.

But we do. It just starts with a bit of belief.

Le Corbusier espoused his Modern belief set for the world in a 1923 collection of essays entitled Toward a New Architecture. A century later, we find ourselves in need of a new general philosophy on how to structure and interact with our built environment. Our surroundings impact us too much to acquiesce to our unacceptable status quo.

And so, on the pages that follow, I propose a new general philosophy for our world. It’s one predicated on a unity of the pragmatic and romantic. There are very many serious challenges facing North America: climate change, lack of affordability, economic stagnation, segregation, prejudice, structural fragility, declining physical and mental health. The list goes on. None of these challenges, however, are insurmountable. There are no immutable laws of the universe which say we cannot address them head on. To let these challenges continue out of some laziness or cynicism towards embracing change is deeply harmful. Optimism is the required course of action to take.

In our pursuit of Optimism through pragmatism, we must take caution that the achievement of our goals does not come at the expense of the people they’re meant to serve. We could theoretically solve our housing crisis by building 10 million concrete cottages measuring 500 square feet at a distance no closer than 60 miles to the core of a dozen major cities, but many other challenges, perhaps more severe, would accompany this proposed solution. The places that are the most utilitarian, in their courtship of lowest common denominator answers, often find themselves the most poorly equipped in the march towards longevity, privileging myopic solutions such as they do. That the most marginalized must accept a cruel spartanism is an iniquity not often discussed. We must seek to do more.

We must create a better world. One that is beautiful, aspirational, dynamic, diverse, sustainable, walkable, affordable, opportune—but not utopian, as utopias have no place in reality. They’re purely fictional. The definition of utopia is “no place”. We very much want to build real places. And what’s more, we know what these real places could look like. All of the listed Optimistic elements have been made manifest in our world before to great effect. A select few places have been able to harness these elements together at the same time. Even fewer have made these conditions last, at scale, for the many. Ours is a mission of abundance such that these kinds of places may become available to as much of the population as possible, without subsidy (familial or governmental, as these are subject to the caprices of varying administrations, or the winds of time), tradeoff, or coercion. Leveraging an Optimistic mentality, we can solve the problems plaguing our world today effectively and wonderfully.

Optimism is inherently a positive force. But lose it, or adopt a worldview that rejects humanity in favor of something else, and we quickly regress. Where the East End of London was, for a time, one of the worst patches of land one could stumble across in the world, it’s now one of the most desirable. In and around the areas redeveloped by social reformers, and sometimes in the buildings created by the reformers themselves, rents are among the most expensive in the United Kingdom. These places, optimistic though their genesis was, have arguably become too successful. Alfred Tredway White’s Workman’s cottages now sell for millions of dollars, on the rare occasions they do come up for sale.

It would be wrong to forget the context of why the remnants from this era were created in the first place, and disregard the conditions that have (mercifully) been left to the past. It would be equally wrong, however to ignore the triumph of these interventions, and the lessons their creation has for us. Regretfully, we are guilty of this transgression. Caught in between an ardent preservation that’s content to maintain the past, and a lapse in the collective memory of the conditions that led to the creation of the places we so revere today, we are lost. Untethered from our history, we cling frantically at those few shreds of good that we enjoy lest they meet the same fate as their perished siblings. If we love these places so much, pragmatism would demand we simply create more of them. It’s inconceivable that housing once developed for the most marginalized is now out of grasp for all but the wealthiest simply because we stopped creating these sorts of places. An artificial scarcity has divorced context and common sense, and the least advantaged groups pay the cost. We cannot look back at a job well done and rest on those laurels forever. Without sufficient watering and replenishment, those laurels will die.

If architecture is an honest reflection of a society’s values—and what could be more telling than the structures we erect that we labor our whole lives to acquire and then reside among—what does it say about ours? Are we a people devoid of ambition, morality, and meaning? If we don’t respect the project of building cities, or societies, that’s one thing, but I don’t believe that to be true. So the question becomes: what do we want our buildings to say about us? What do we value? Do we worship at the feet of Gods, or commerce? Do we withdraw into ourselves, or do we hold sacred communion with our neighbors? Do we seek a higher plane of living, or are we content with whatever scraps we’re provided? Our values can be read in wood and stone, and the stories they tell are incorruptible. What tales will we tell?

Working towards crafting new stories about who we are will doubtless be challenging. Much of the last century has proven how difficult the right sort of storytelling is. And yet, I’m hopeful. I’m hopeful because we know how to create places that are fundamentally good for our well being, physical health, mental disposition, economy, safety, social structure, and a host of other metrics. We know how to create joyous realms that are worthy of our affections. We’ve done it before. Ambition alone, or clutching to an idealized past, is not enough, however. We cannot simply want to do good. We have to acknowledge, and then respond, to the operating realities that we’re constrained by today. Even the smallest of projects requires buy-in from many dozens of people, from public officials, bankers, and neighborhood groups, to architects, graphic designers, code enforcers, and construction trades. Getting all of these people to believe they’re on the same team is no simple thing.

So, how do we go about doing this? How do we progress the built environment forward in the next century when it has regressed so far in the last? It starts with the belief that we can create great places anew—a belief that a better world is not only possible, but essential to cultivate. We can accomplish this by looking at examples of great places that have been built recently and within our context, not 200 years ago in a place opposite the world from us. Inspiration then leads to realization. When people see that something can be done, they’ll be more inclined to do more things like it in the future. When they think it’s impossible—or don’t see anything like it at all—there’s little hope of creating something better. One cannot very well move forward with something they have no knowledge of, or do not think has any reasonable chance of success. How could you think about doing something if you’ve never seen it done before? Creating something without a reference to existing precedents is very hard. Thankfully, we have references.

The first precedents for this contemporary strain of Optimism can be traced back to the pioneering work of the first New Urbanists. Driven by a desire to rectify the ills of midcentury planning and sprawling development patterns, a small group of architects and planners (Andrés Duany, Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, Elizabeth Moule, Stefanos Polyzoides, Peter Calthorpe, Hank Dittmar, and Daniel Solomon, among others) formed the Congress for the New Urbanism in 1993. According to the founding charter, “The Congress for the New Urbanism views disinvestment in central cities, the spread of placeless sprawl, increasing separation by race and income, environmental deterioration, loss of agricultural lands and wilderness, and the erosion of society’s built heritage as one interrelated community-building challenge”.⁴¹

These principles have informed a generation of practitioners of the built environment, both directly and indirectly. They form part of an Optimistic philosophy, but more is needed. Where the Modernist planners espoused hyper rationality, individualism, an embrace of technology, minimalism, and orthogonality, the Optimist privileges the pursuit of walkable, sustainable, organic (spontaneously occurring), affordable, beautiful, malleable, contextual, stylistically agnostic, diverse, and common sense communities that adhere to the needs of people first. Optimism is a perspective that welcomes technology and innovation, but only when they complement humanity, not usurp it. Importantly, the Optimist embraces an abundance agenda that advocates for building as many high-quality places as possible that adhere to these underlying principles such that as many as possible may access fundamentally good communities, without scarcity, bad faith regulation, or hostility inhibiting them. Optimism may prefer the construction of infill projects on lots in existing urban areas, but it also provides the framework for town extensions in greenfields such as they may be required.