Written by Robert Orr.

Zoning is often described as a thoughtfully considered, practical tool—a way to keep factories away from homes or to preserve the “safety” of neighborhoods. However, the deeper story behind zoning in America is far more complex and revealing. At the center of that story is a man you’ve probably never heard of: Harland Bartholomew (1889-1989).

Bartholomew wasn’t a mastermind. He wasn’t even trained as a planner. He was a young, behind-the-scenes worker—essentially a new hire with no formal academic or professional background—sent to Newark by the E.P. Goodrich firm.

Why?

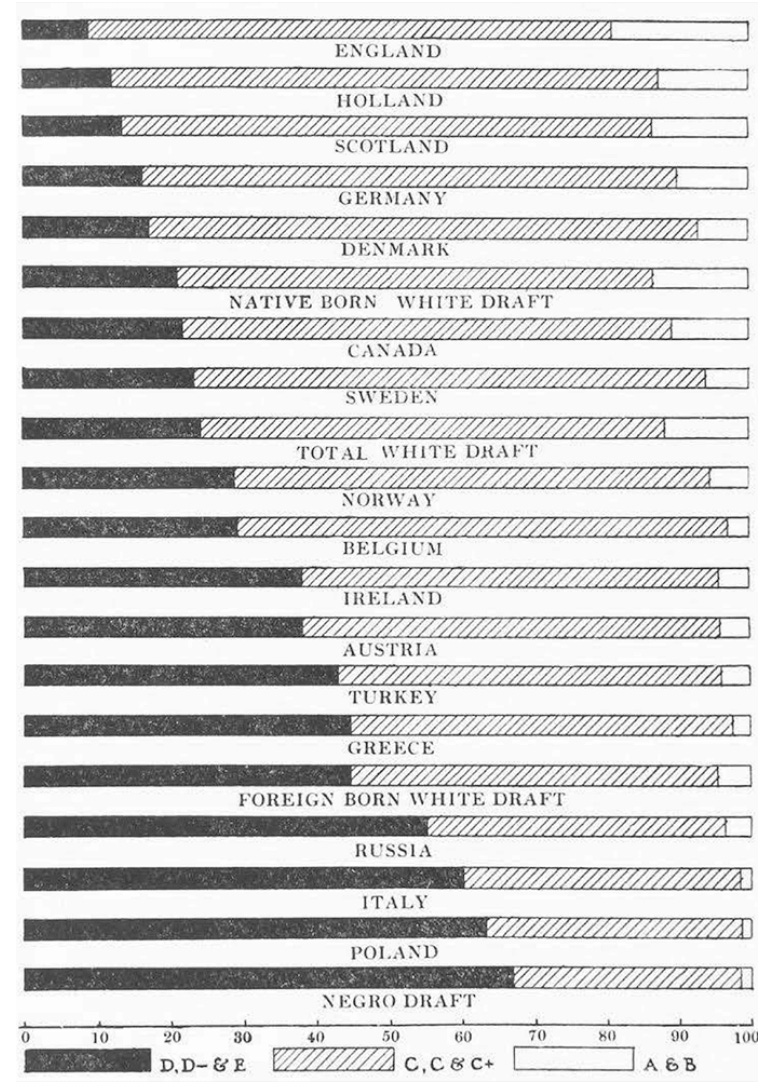

Without exaggeration, city officials were terrified by the 1911 Federal Dillingham Commission’s 27,000-page report, which outlined the “dangers” posed by the new types of immigrants from southern and eastern Europe and Ireland. The report validated the emerging “science” of eugenics, a veritable hotbed of research among America’s leading scientific circles.

So pronounced was the passion for this “breakthrough science” that even Hitler remarked, “There is today one state in which at least weak beginnings toward a better conception are noticeable. Of course, it is not our model German Republic, but the United States.”

Into this firestorm walked Harland Bartholomew—not with a mission, but with a notebook.

He was no Robert Moses figure, wielding raw political power to reshape cities. He was simply a proxy for a civil engineering firm that knew nothing about the subject of ethnicities they were assigned to examine. And that, perhaps, is what made Bartholomew’s work so endearingly dangerous. He didn’t question the ethnic or class prejudices expressed vituperatively by the property owners he interviewed. He just noted their comments verbatim and drew a crude map, blocking out the city’s ethnic neighborhoods.

When he issued his report, his lack of academic and professional experience prevented him from recognizing the need for edits. He simply transcribed what he heard. However, his unpolished language struck a chord, immediately igniting what could only be described by contemporary standards as rapture by property owners. The rapture spread like a house afire, transforming raw prejudice into official policy without a second thought from city to city.

What we now call “NIMBYism” (Not In My Backyard) was taking shape. At that time, concerns focused on “neighborhood decline,” but hidden fears involved immigrants “lowering” property values. As historian Katherine Benton-Cohen explains in her book, Inventing the Immigration Problem (2018), these fears were tied to class, culture, and an increasing hysteria over a dominant class losing control.

Bartholomew’s early city plans quietly embedded those fears into the physical structure of American cities. In St. Louis, for example, he helped develop zoning maps that blatantly segregated neighborhoods by ethnicity and income.

It’s important to note that the Great Migration—when six million Black Americans moved north to escape Jim Crow—happened a bit later. It was then that race was added to ethnic segregation, using the mindset that was already in place. The issue all along was a deep suspicion of anyone seen as “less than”— regardless of race, origin, or background.

Even after ethnic and racial zoning was declared illegal in 1917 (thanks to Buchanan v. Warley), Bartholomew and the framers of zoning exchanged approaches to use “lack of affordability” to uphold the same segregationist policies.

Their three principal new zoning tools included:

Minimum property size to prevent subdividing into cheaper lots

No multifamily to prevent subdividing buildings into less expensive apartments, and

Separation of uses to prevent less expensive access to amenities in close proximity, such as corner grocers.

Cleverly, social reformer Lawrence Veiller (1872–1959) saw the opportunity to leverage the prejudice further by plugging in the policing powers behind fire codes. Veiller argued:

“Do everything possible in our laws to … penalize so far as we can in our statutes, the multiple dwelling of any kind... If we require multiple dwellings to be fireproof, and thus increase the cost of construction; if we require stairs to be fireproofed, even where there are only three families; if we require fire escapes and a host of other things, all dealing with fire protection, we are on safe grounds, because that can be justified as a legitimate exercise of the police power... In our laws, let most of the fire provisions relate solely to multiple dwellings to increase costs, and allow our private houses and two family houses to be built with no fire protection whatever (NHA Proceedings 1913, 212).”

Although many assume zoning enabled car use, the opposite was true.

Car use, which came later, enabled zoning. In fact, car dependency not only enabled the physical displacement of people according to zoning policies but also engineered social isolation. The car allowed each person to exist in their own solitary confinement. Public space, where mingling once happened by default, gave way to sprawling subdivisions, driveways, and cul-de-sacs. Neighborhoods lost their mix, and with it, their habits of shared community.

Bartholomew’s naivety disrupted longstanding, robust routines that cemented community bonding. By the end of his long career, the effect was like an invisible plague wafting silently across horizons. Without trace or resistance, his eugenic policies infected more than 4,000 cities, blazing trails of prejudice and deceit.

The property (pride) and prejudice conundrum, to borrow from Jane Austen’s 1813 novel, would today focus on Austen’s Mr. William Collins character. A minor character at the time of publication, two centuries later, Collins serves as a critique of contemporary social and economic pressures by being clueless about social cues, obsessed with status and his patron, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, and unable to understand genuine affection or social norms. Better than the Elizabeth and Mr. Darcy characters of their day, Mr. Collins reflects the cycle of fear, status, and distancing, which clings to Americans like stink on a monkey.

This isn’t just history.

Sadly, it’s the blueprint for most American suburbs today: car-dependent, isolating, and costly to access. The most impacted are still those without wealth, language skills, or political influence. After such thorough erasure, it may seem hopeless to restore the millennia-long social aspect of running errands in public spaces where people accidentally bump into each other while doing the same.

But there’s hope.

The core issue of “quality” discrimination is under question. Belgian/French anthropologist and ethnologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009) established that all humans are born with the same organs. Their differences are shaped by experience, not eugenics.

On her On Point radio show, Meghna Chakrabarti recently examined the challenges faced by American boys—how many feel lost, left behind by social changes, and unsure how to find purpose, with an alarming number taking their own lives. What she discovered through research was unexpected: most boys do not fit the stereotype imposed on them. They aren’t craving macho power. They want to be part of something. They want to help. They seek connection, not control.

That insight is crucial for urban planning. Dismissing wishful thinking that the “immigration problem” can mysteriously vanish through harsh punishments, if we design cities that prioritize connection over hierarchy—places where people of different incomes, genders, ethnicities, races, and backgrounds can coexist as one species without sacrificing heterogeneity—we may tap into our natural instincts for community, purpose, and collaboration, per Chakrabarti’s advocations. If that happens, we can start addressing genuine issues that truly matter, rather than wasting time on futile rescue efforts aimed at managing foolish behaviors that dominate tabloids today, only to exacerbate situations. For example, the LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) accreditation system’s efforts to promote rescue rewards like bike racks and native grasses only encourage wrongdoers to push further out on a limb with their largely unsustainable practices.

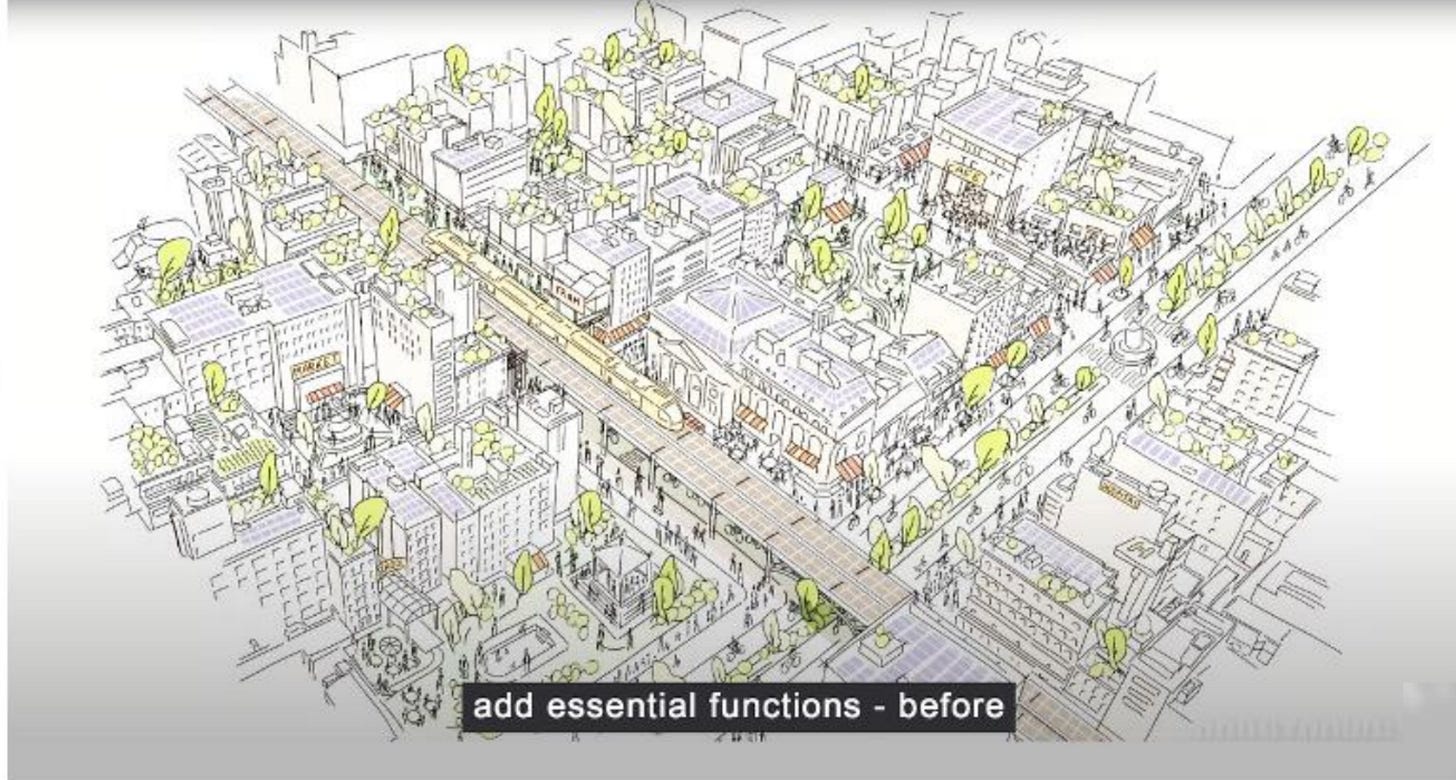

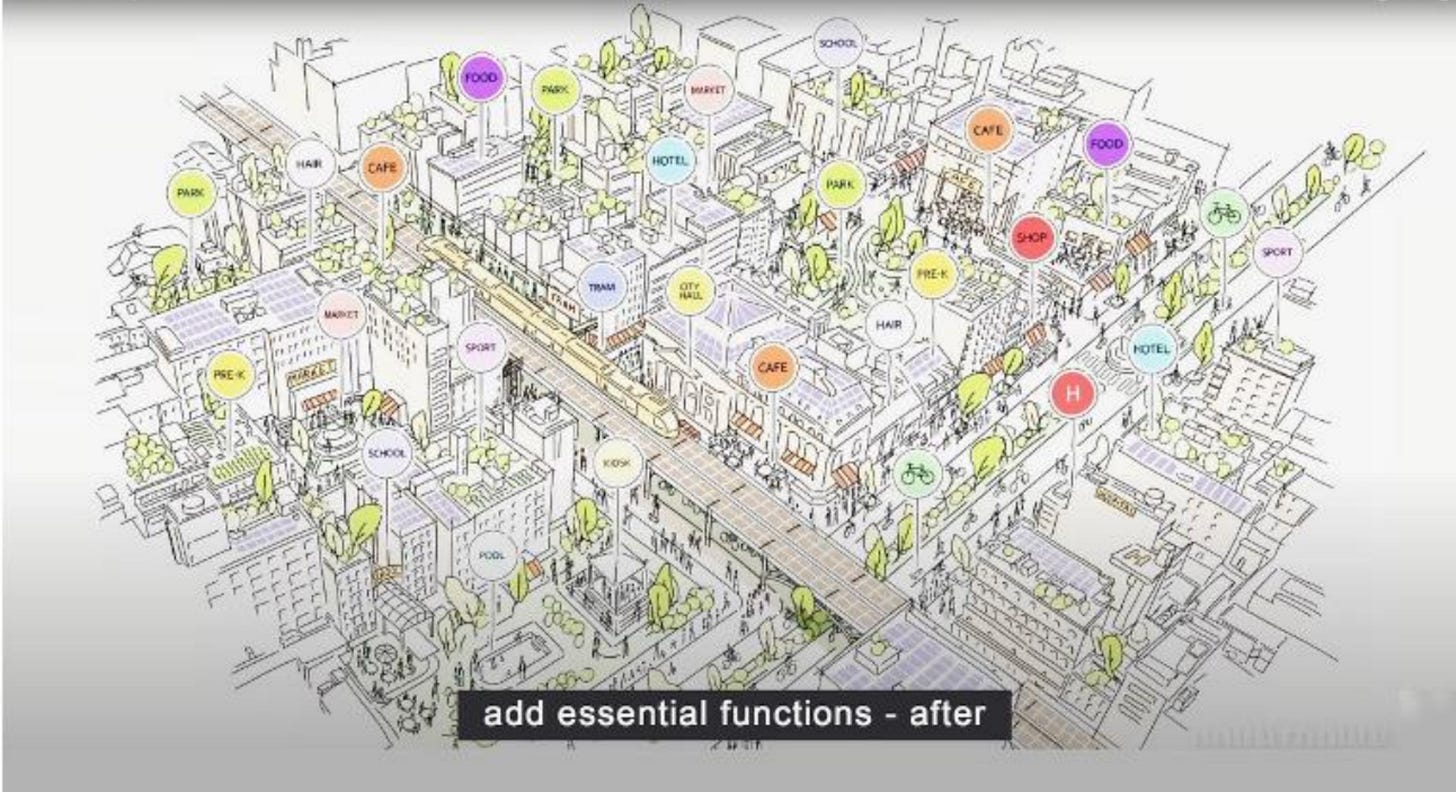

Movements like New Urbanism aim to achieve that goal. Through walkable neighborhoods, mixed-use developments, smaller affordable housing units on smaller affordable lots, and expanded public transit, they try to undo the isolation that Bartholomew unintentionally helped create.

However, even New Urbanism sometimes overemphasizes mobility—focusing too much on moving people from point A to point B, instead of on the people themselves.

Carlos Moreno, a software engineer turned urban thinker, offered a fresh perspective on the missing piece in New Urbanism when reimagining Paris. Originally focused on city navigation, an epiphany made him reverse the model: What if cities weren’t just places to pass through, but complete ecosystems within themselves, like compact computers with which he was so familiar? His concept of the 15-minute city wasn’t about movement—it was about proximity.

In his model, Moreno identified six functions of life—living, working, goods and services, education, healthcare, and culture and recreation. By locating all functions, or multiples of functions, within a short walk, they become much like the full set of functions packed inside a smartphone, so small that it can be held in one hand.

Like the smartphone, there must be enough users to financially support all the functions contained within the small space—not just people nearby, but more people nearby. In an urban setting, basic demographics can help strike a balance between providers and users through simple mathematics, particularly when walking takes precedence over other modes. By the same token, when everything one needs can be reached in a short and appealing walk, other modes become optional.

Moreno’s method: simply add functions (in cities other than Paris, low, street related density must be added as well).

Rebecca Solnit reminds us in A History of Walking,

“The magic of the street is the mingling of the errand and the epiphany.”

Zoning is a flawed idea driven by selfish interests and naivety. Some studies suggest that other factors, such as access to guns and lax immigration policies, influence what is widely regarded as dystopian desocialization, marked by frequent acts of unspeakable violence. However, a growing consensus confirms that zoning and car dependency are the only causes that consistently reduce interaction and community bonds, and those two factors alone account for most of the desocialization. It turns out that interaction and community bonds are also the most crucial factors for building health, happiness, and long lives. It’s important to note that socialization does not come from organized spectacles and events, despite their entertainment value. Rather, true bonds come from the studious choreography of daily routines.

Weak, baseless arguments from spreadsheet-obsessed planners, misguided policing regulators, icon-orbiting architects, and abuse-enabler engineers have wasted a century fueling distrust, anger, polarization, and violence. Still, they shouldn’t be blamed. Since their policies are rooted in popular prejudice, we all share responsibility for building such a formidable blockade against our natural human tendencies toward socialization and getting along in communities.

It then follows that removing the blockade could release innate human tendencies from their ill-begotten captivity, unleashing a powerful wave to fill the empty void left by the super-human descaling of cohesion by industrialized consorted prejudice. Such a massive wave would flush out festering tumors of rancor and self-destruction and spark a renaissance of rekindled relationships. This natural phenomenon, of course, would be limited to locations where blockades fall.

Any spread would have to be through infection rather than indoctrination.

Cynics argue that people will always choose the convenience of driving, even when faced with the high likelihood of wasted hours on endless traffic jams and the life-shortening stress of participating in “road rage.” Currently, the costs of owning a car are nearly as high as owning a house. This financial instability may force many to reconsider their priorities, especially if viable and appealing alter-natives become available and healthy friendship circles expand. Cities that developed long before the introduction of automobiles, like Siena below, allow one to “test drive” such an alternative and draw inspiration and conclusions.

Another important reason to challenge the cynics is that, for the first time in many decades, inexplicable cravings for face-to-face social interaction seem to be reemerging among many young people—a sign, as Lewis Carroll would say, “The time has come.”

Bernard Rudofsky wrote in 1969, “Streets are for people,” signaling that a plan to manage open floodgates is already in place. In fact, it’s been around since the beginning of civilization, only abandoned in the last century. Innate human tendencies to prefer driving may be ingrained, but the period of ingraining is trivial compared to the long history of innate human tendencies to value relationships.

All we need to do is reset the goal of planning to choreograph daily routines by strategically locating functions to maximize opportunities for frequent encounters, break down blockades, and trigger primal social instincts. Such traits will be free to develop routines, without any help from indoctrination, that promote frequent encounters, as they always have. Let’s house people closer to their needs and let the walking begin.

This article by Robert Orr originally appeared in SmartGo Blog and is republished here with permission.