AFFORDABILITY | To Solve for Housing Costs, Look To Tokyo

The Japanese capital proves that flexible land-use rules help keep prices stable

Written By David Berger

One often hears that the laws of supply and demand do not apply to housing markets. As an economist by trade, I may be biased, but I believe that nothing could be further from the truth. The Triangle can benefit from this knowledge—if we enact zoning reforms that push supply in the right direction.

What is the supply and demand framework?

At its core, the supply and demand framework is way of understanding how buyers and sellers interact in a market. If the price of a good is high, people are willing to supply more of that good (if they can), while buyers demand less of it. We can use this framework to understand how prices will adjust when supply and demand change. If more people want to purchase something (demand increases), or if it becomes more expensive to make more of something (supply decreases), we would expect prices to rise. This immediately gives us two possible reasons why housing might be expensive: Either many people want to purchase it (high demand), or there are not enough homes for sale (low supply).

Do you have any data to back this up?

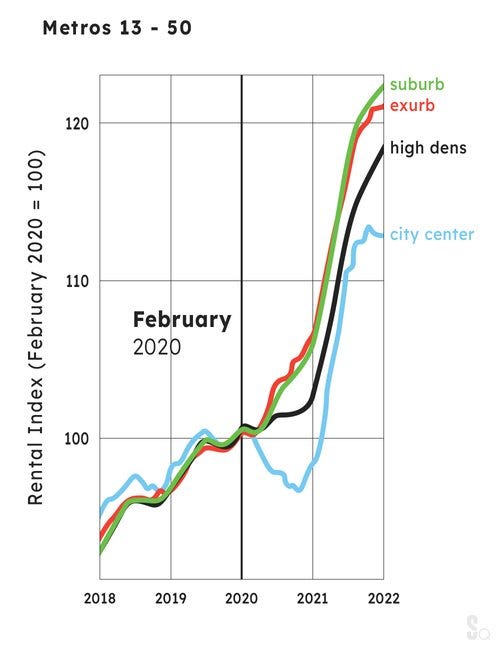

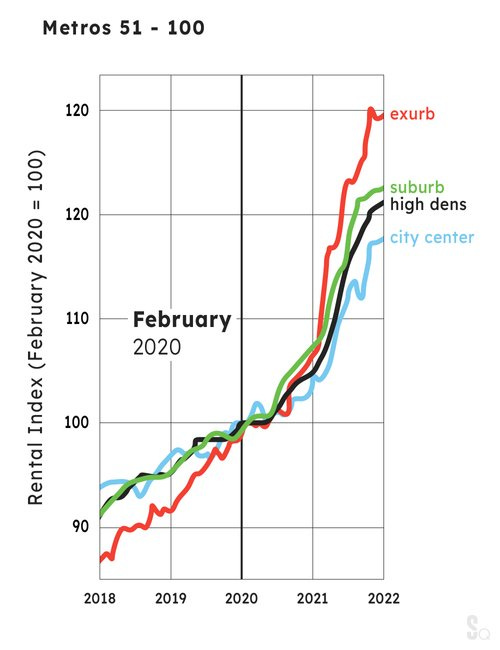

Yes. Consider housing markets around the onset of COVID-19 in early 2020. As people locked down and many jobs went remote, some left dense downtowns (like New York City, San Francisco, and Chicago) for more space in the suburbs and smaller towns. A recent paper by Stanford Economist Nick Bloom and his co-author Arjun Ramani explored the implications of these events for rents and house prices. The supply and demand framework makes multiple predictions, all of which are borne out in the data. It suggests that rents should have fallen in the most dense city centers where demand fell the most (left panel), and they should have risen the most in the suburbs and smaller metro areas where demand increased (all panels).

Zillow rental data from Arjun Ramani and Nicholas Bloom, “The Donut Effect,” from the National Bureau of Economic Research (May 2021). Largest twelve cities are New York City, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Dallas, Houston, Miami, Philadelphia, Washington, Atlanta, Boston, and Phoenix.

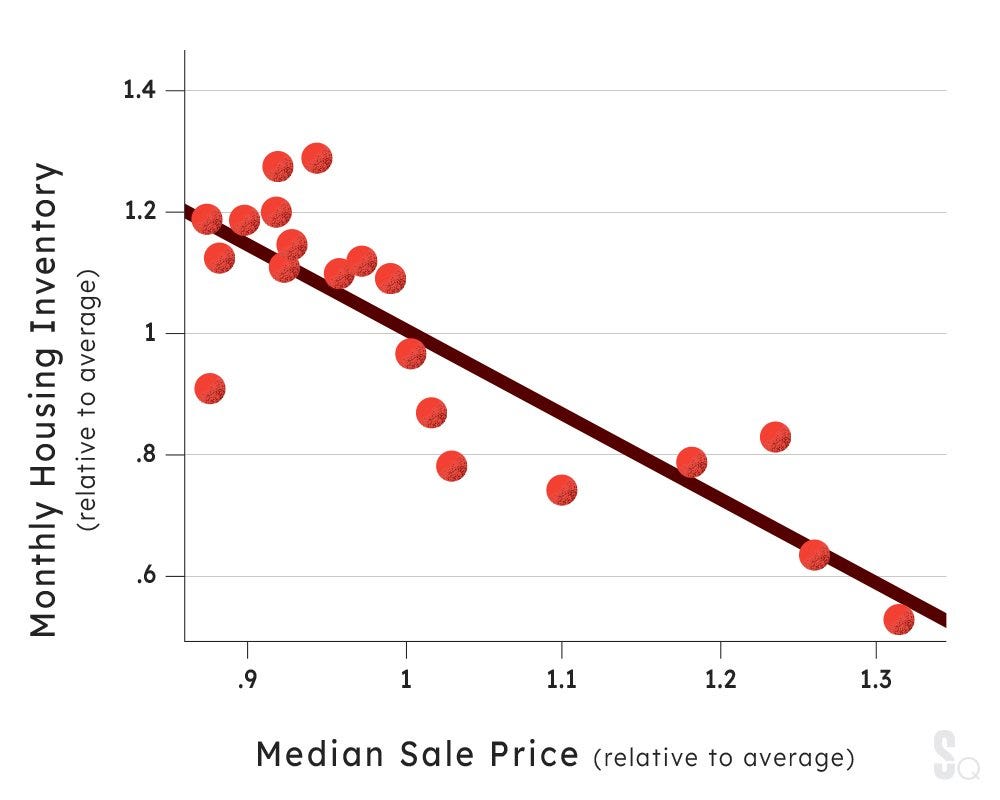

Closer to home, we can examine the relationship between supply and demand directly in the Durham housing market. The figure below plots the relationship between the amount of housing inventory available in a given month (a key measure of housing supply) and median sale prices over the period 2018-2022. As is clear, when there is less supply (i.e., inventories are below average), houses sell for more than they would typically. Once again, the supply and the demand story is confirmed by the data.

Why are housing prices rising so quickly in the Triangle?

Now that we can agree that the laws of supply and demand apply to housing markets, we can use this framework to understand why house prices are growing so rapidly. First, there are a lot of demand-side pressures: The Triangle is one of the fastest-growing areas in the country because there are plentiful jobs and nice weather. Second, at least until recently, mortgage rates were low, allowing people to afford more expensive houses. Third, we did not build enough homes, so supply was limited. All of these factors came together to make prices increase.

Can building actually help? It seems that more building just leads to higher house prices.

Yes, building can really help. The best evidence comes from Tokyo. Despite it being a world-class city, on a par with New York City and London, you might be surprised to learn that since 2000, house prices in Tokyo have been roughly constant, while they have more than doubled in New York City and San Francisco. Tokyo is able to maintain affordability by removing local restrictions that limit new building (e.g., local planning commissions, rent control measures, and height constraints—all of which are pervasive in America), ensuring that enough new housing is built to satisfy demand. By some estimates, the Japanese build at twice the rate we do. The net result is that prices in Tokyo remain affordable, while prices skyrocket in the U.S.

The cautionary tale of Chapel Hill reinforces the danger of not building enough. In the 1990s, NIMBY-leaning neighbors got control of the Chapel Hill City Council and put into place zoning restrictions that made it much more difficult and costly to build new housing. As of now, average price of single-family home in the town is over $625,000.

Conclusion

How can we make housing more affordable in the Triangle? As this article has made clear, there are two alternatives for lowering prices. On the one hand, we could increase supply by removing local zoning restrictions, making new construction cheaper and allowing for more housing to get built. On the other hand, we could lower demand to live in the Triangle by somehow convincing people to not want to live here. Hopefully, the choice is clear.

David Berger is a Professor of Economics at Duke University. His research interests include Macro/Monetary, Housing, Labor and Finance.